Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Credibility and Expectation Gap in Reporting On

Загружено:

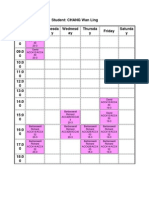

Wan LingИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Credibility and Expectation Gap in Reporting On

Загружено:

Wan LingАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Managerial Auditing Journal

Emerald Article: Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Junaid M. Shaikh, Mohammad Talha

Article information:

To cite this document: Junaid M. Shaikh, Mohammad Talha, (2003),"Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties", Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 18 Iss: 6 pp. 517 - 529 Permanent link to this document: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02686900310482650 Downloaded on: 30-04-2012 References: This document contains references to 47 other documents Citations: This document has been cited by 2 other documents To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com This document has been downloaded 4152 times.

Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by UNIVERSITI MALAYSIA SABAH For Authors: If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service. Information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Additional help for authors is available for Emerald subscribers. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com With over forty years' experience, Emerald Group Publishing is a leading independent publisher of global research with impact in business, society, public policy and education. In total, Emerald publishes over 275 journals and more than 130 book series, as well as an extensive range of online products and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 3 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

*Related content and download information correct at time of download.

Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties

Junaid M. Shaikh Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia University, Melaka, Malaysia Mohammad Talha Faculty of Business and Law, Multimedia University, Melaka, Malaysia

Keywords

Corporate governance, Reports, Financial reporting

1. Introduction

One of the many issues that involve the accounting profession and the community is the expectation gap that exists in accounting engagements. The expectation gap was originally defined as the difference between levels of expected performance as envisaged by auditors and users of financial reports. It is:

. . . the gap between society's expectations of auditors and auditors' performance, as perceived by society.

Abstract

This paper analyzes and reports on studies that examine the extent to which international auditing boards have accomplished the goal of reducing the expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties. This is because there has been a long-running controversy between the auditing profession and the community of financial statement users concerning the responsibilities of the auditors to the users. Enron and WorldCom scandals have provoked the public to incite the government and professional bodies to impose stringent regulation in protecting their interests. It also suggests the solutions to minimize the gap and enhance the public's perception towards the profession.

corporate governance and financial reporting practices have again received wide coverage by the media, and grabbed the attention of regulatory bodies, stock exchanges and the accounting profession.

2. Literature review

Companies should close credibility gap in books

In his findings, Murray (2002) has indicated that some leading American corporations have teamed up with unscrupulous accountants to mislead shareholders about how much money they make and also mislead the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) about how little money they make. The result is a huge and growing gap credibility gap which is between book income and taxable income. If the efforts at accounting overhaul now under way are to be successful, they will need to close that yawning gap from both ends. For example, the case of WorldCom Inc., between 1996 and 2000, the company reported $16 billion (e16.14 billion) in earnings to its shareholders. But to the tax authorities, it reported less than $1 billion of taxable income. The truth undoubtedly lies somewhere in between. Enron Corp. has a similar story. To its shareholders, it reported profits of $1.8 billion between 1996 and 2000. But it told the IRS it lost $1 billion during the same period, according to calculations by Robert McIntyre of the labor-backed group, Citizens for Tax Justice. Kmart Corp, to take another name in the news, reported $1.6 billion in profits to its shareholders, but a loss of $51 million to the IRS. The games that allow companies to achieve such anomalous results are often the brainchildren of clever accountants and investment bankers. One particularly

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at http://www.emeraldinsight.com/0268-6902.htm

The expectation gap has been attributed to a number of different causes (www.corpgov.net): . the probabilistic nature of auditing; . the ignorance, naivety, misunderstanding and unreasonable expectations of non-auditors about the audit function; . the evaluation of audit performance based upon information or data not available to the auditor at the time the audit was completed; . the evolutionary development of audit responsibilities, which creates time lags in responding to changing expectations; . corporate crises which lead to new expectations and accountability requirements; or . the profession attempting to control the direction and outcome of the expectation gap debate to maintain the status quo. While a consensus as to the causes of the audit expectation gap has not been achieved, its persistence has been acknowledged and bears testimony to the profession's inability to remove the gap, despite attempts to do so by educating the public and codifying existing practices. Following recent well-publicised failures by large listed companies in Australia and overseas, aspects of audit independence,

The Emerald Research Register for this journal is available at http://www.emeraldinsight.com/researchregister

Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529 # MCB UP Limited [ISSN 0268-6902] [DOI 10.1108/02686900310482650]

[ 517 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

egregious tactic used by Enron was the now infamous ``MIPS'' a security invented by Goldman Sachs that counted as debt on the company's tax return, but equity on its public books. Regardless of whether MIPS technically complied with the law, it was a sham. Any honest accountant or tax lawyer who works at one of the big accounting firms would say that such tactics have become increasingly common, and increasingly outrageous. Indeed, fierce arguments have occasionally broken out at those firms between publicly minded tax experts who still feel some obligation to abide by the spirit of the tax laws, and profit-minded partners eager to find clever new ways to exploit every loophole in the law. Lying to shareholders and lying to the IRS are just opposite sides of the same coin. Accounting is no longer a way to provide an accurate and unified view of a company's finances. The fact that accountants have become so ``good at serving'' both shareholders and the IRS is the clearest evidence of the corruption of their profession. As a solution, Murray emphasizes that publicly traded companies should be required to make tax returns public. That kind of information may not be much use to the average investor. But conscientious stock analysts surely there are some out there? could spend their time analyzing the gaps between book and tax income, attempting to find truth in between. Congress and the Securities and Exchange Commission should work to bring the two measures of income into closer alignment.

demonstrated that serious, deeply rooted problems may exist. It should be recognized that these areas are the keystones to protecting the public's interest and are interrelated. Failure in any of these areas places a strain on the entire system. The effectiveness of the system of corporate governance, independent audits, regulatory oversight and accounting and financial reporting, which are the underpinnings to the capital markets, to protect the public interest has been called into question by the failure of Enron. The rapid failure and bankruptcy of Enron has led to severe criticism of virtually all areas of the financial reporting and auditing systems, which are fundamental to maintaining investor confidence in the capital markets. This situation raises a number of system issues for most professional considerations to better protect the public interest. These protections would include regulation and oversight of the accounting profession, the independent audit function, accounting and financial reporting model and establishment of professional body to govern the acts of the accounting profession.

Auditors' and investors' perceptions of the ``expectation gap''

Protecting the public interest

In the study, Walker (2002) found out the facts regarding Enron's failure still being gathered to determine the underlying problems and whether any civil and/or criminal laws have been violated. At the same time, the Enron situation raises a number of systemic issues for congressional consideration to better protect the public interest. It is fair to say that other business failures or restatements of financial statements have also sent signals that all is not well with the current system of financial reporting and auditing. As the largest corporation failure in US history, Enron, however, provides a loud alarm that the current system may be broken and in need of an overhaul. The authors will focus on four overarching areas corporate governance, the independent audit of financial statements, oversight of the accounting profession, and accounting and financial reporting issues where the Enron failure has already

McEnroe and Martens (2002) have extended the prior research by directly comparing audit partners' and investors' perceptions of auditors' responsibilities involving various dimensions of the attest function. This study surveyed public accountants and individual investors to obtain their perceptions of the extent to which an expectation gap exists in several dimensions of the attest function. Investors were surveyed because they were the main users of financial statements and are the most appropriate subjects to employ as representatives of the public and financial statement users. Audit partners were included as the group on the other side of the expectation gap. The research was conducted over a decade after the release of the expectation gap SASs and also after the issuance of SAS No. 82 (AICPA, 1996). Throughout the research, McEnroe and Martens (2002) found that an expectation gap currently exists: investors have higher expectations for various facets and/or assurances of the audit than do auditors. The findings served as evidence that the accounting profession should engage in appropriate measures to reduce this expectation gap. The findings also indicated that an expectation gap exists, investors had higher expectations for various facets and/or assurances of the audit than do auditors in the following areas: disclosure, internal

[ 518 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

control, fraud, and illegal operations. It was also discovered that investors expect auditors to act as ``public watchdogs'' (www.isaca.org/standard/guide1.htm).

Marian et al. (2002) suggest that to close the gap more completely, the audit profession and financial community need to reexamine the fundamental role of an audit in society and make sure financial statement preparers, users and auditors all are in agreement. It was revealed that as long as users and auditors continue to have different understandings of the real meaning of ``present fairly'', according to the GAAP, the gap will remain. The research was carried out by comparing the audit report from 1948 to 1988. Except for minor editorial changes, the standard audit report remained virtually unchanged from 1948 to 1988. During this period, there was concern that users might not be correctly interpreting the auditors' intended messages, and major revisions were considered. However, these attempts to revise the standard audit report failed to attract widespread support. The evidence of the research suggested that investors seek very high levels of financial statement assurance. Auditors should not only be interested in, but also be aware of these shareholder perceptions. The litigious environment in which accountants operate mandates that we, individually and as a profession, monitor public opinion and attitudes toward the level of services and assurance provided. Marian et al. (2002) stated that if investors expect, and courts begin to uphold, a standard of absolute assurance, audit liability inevitably will increase substantially. Thus, it was necessary from both societal and professional perspectives that accountants try to narrow the expectation misunderstanding gap. The research found out that the gap may be narrowed partly through increased public understanding of an audit, its nature and its inherent limitations. Accountants should devote substantial resources to explaining to the public the auditor's current role in the financial reporting process and an audit's inevitable limitations. Increased educational efforts with clients and audit committees at shareholder meetings, in professional and civic organizations and at every available juncture should be used to communicate an audit's merits and limitations. A more direct approach to increasing user awareness of the audit function was also recommended in the

The expectations-performance gap in financial reporting from the perspective of Hong Kong bank loan officers

paper. In addition, the Securities and Exchange Commission should be encouraged to develop a similar unbiased report to be presented with registrants' filings and financial statements. Besides, Marian et al. (2002) suggested that a SEC communication regarding the audit function and the assurances provided may be more convincing to financial statement users than one emanating from auditors.

Theories of ethics and moral development

Ethics in general is defined as the systematic study of behavior based on moral principles, philosophical choices, and values of right and wrong conduct. Similar to general ethics, ethical behavior from a professional standpoint also involves making choices based on the consequences of alternative actions. As stated in the following passage from The Philosophy of Auditing by Mautz and Sharaf (1961, p. 232):

Ethical behavior in auditing or in any other activity is no more than a special application of the general notion of ethical conduct devised by philosophers for men generally. Ethical conduct in auditing draws its justification and basic nature from the general theory of ethics. Thus, we are well advised to give some attention to the ideas and reasoning of some of the great philosophers on this subject.

Previous research on ethical issues in accounting has generally avoided philosophical discussions about ``right and wrong'' or ``good and bad'' choices. Instead the focus has been on the ethical or unethical actions of accountants based on whether they comply with rule-oriented codes of professional conduct. Various theories of ethics have been made known and used to determine ethical dilemmas, but the two existing theories applicable to CPAs are utilitarianism and rule deontology: 1 Utilitarian principle. Utilitarianism is based on the ``greatest good'' criterion. According to this principle, when faced with an ethical problem, the consequences of the action are evaluated in terms of what produces the greatest amount of good for the greatest number of people. The stress here is on the consequences of the action rather than on the following of rules. 2 Rule deontology. Rule deontology is a deontological theory and is based on a duty to a moral law. Thus, the accountant's actions rather than their consequences become the focus of the ethical reasoning process. According to this principle, an accountant is morally bound to act according to the

[ 519 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

requirements of a rule of conduct of the code without regard for the effects of that action. If utilitarianism is applied, each situation involving confidential client information would have to be evaluated to determine if it would be morally right to reveal the information (this does not relate to those situations that are specifically excluded in Rule 301). The confidentiality rule would be followed only if that course of action produced the greatest good to the greatest number of people. If rule deontology is applied, however, the Professional Code of Conduct would be followed in all circumstances involving client confidential information (except as stated in the code), despite the consequences. The findings of studies indicate that CPAs usually adhere to the code (rule deontology) in resolving issues concerning confidentiality. However, such decisions are not always according to what they see as ``good ethical behavior''. The broad principles of the code indicate that ethical conduct means more than abiding by a letter of a rule. It means accepting a responsibility to do what is honorable or doing that which promotes the greatest good to the greatest number of people, even if it results in some personal sacrifice. Somehow, the profession needs to emphasize the ``greatest good'' criterion more strongly in applying the rules of conduct.

action. Otherwise the credibility of the organization, management, professional and indeed, the professional will suffer. There is no doubt that the public has been surprised, dismayed and devastated by periodic financial fiascos. The list of recent classic examples includes Bre-X, Livent Inc., YBM Magnex International Inc., Enron, and Worldcom. On a broader basis, continuing financial malfeasance has led to a crisis of confidence over corporate reporting and governance. This lack of credibility has spread from financial stewardship to encompass the other spheres of corporate activity and has become known as the credibility gap. Audit committees and ethics committees, both peopled by a majority of outside directors, the widespread creation of corporate codes of conduct, and the increase of corporate reporting designed to promote the integrity of the corporation all testify to the importance being assigned to the crisis. Besides that, professional bodies and the Securities and Exchange Commission should work together to bring the two measures of income into closer alignment.

Expectation gap concerning evaluation of internal control

3. Credibility gap and expectation gap

The battle for credibility

During the past two decades, there has been an increasing expectation that business exists to serve the needs of both shareholders and society. Many people or the community have a ``stake'' or interest, in a business, its activities and impacts. If the interests of these shareholders are not respected, then action usually occurs which is often painful to shareholders, officers and directors. In fact, it is unlikely that businesses or the profession can achieve their long-run strategic objectives without the support of key shareholders. As a result, management and professional accountants, who serve the often conflicting interests of shareholders directly and the public indirectly, must be aware of the public's expectations for business and other similar organizations. More than just to serve intellectual curiosity, this awareness must be combined with traditional values and incorporated into a framework for ethical decision-making and

In the last decades the focus on expectation gap issues has determined many fundamental inconsistency between best-practice standards and the expectations of the primary users of audit services. Maybe the most important incongruity has been between the view on internal control as stated in the auditing standards and the concept of internal control as understood by company management. In the USA, this was recognized in the Treadway report on fraudulent financial reporting, which acknowledged the necessity for a common reference point on the content of internal control. Since this need was clearly affirmed in the late 1980s, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission decided to build up an integrated framework on internal control. The ensuing attempt to provide a framework was published in the COSO Report in 1992. Although the main coverage of this report was a message regarding internal controls intended for management directors, it provides a framework which unambiguously deals with the interests of all parties involved (including auditors, board of directors and regulating bodies). The auditors took this into consideration by updating the particular auditing standard on internal control (the replacement of SAS 55 with SAS 78 ``Consideration of the internal

[ 520 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

control structure in a financial statement audit'' The COSO Report (1992). Overall, the findings of studies suggest that the auditors have not made the needed effort to close a realized expectation gap. One view of these results can be linked to the need for future regulation initiatives. An integrated framework should include the auditor, that is, the auditor has to make known the level of internal control assessments in view of the expectations from the primary users, i.e. that they always perform such evaluations. The conclusion is that a major divergence still needs to be decided on. Another perception is to steer clear of an exact duplication of the described efforts to close the realized expectation gaps as carried out by other national (European) practices in the standard setting efforts concerning internal control.

The expectation gap between users' and auditors' materiality judgments

The concept of materiality occupies a central position in auditing. This is due to a demand for efficiency and credibility on the auditor's report. Materiality thus ``permeates'' the kind and range of all auditing procedures, the selection of items, and the timing of the audit. In auditing and accounting, materiality is defined in different ways in different guidelines and statutory provisions. It has, for example, been included in frameworks in the USA and other countries though not Denmark with greater or lesser degrees of ``precision''. In Denmark, materiality is defined in the Danish statement on auditing standards, and has indirectly been included in an auditing context in official audit report regulations from 1996. In ISA No. 25 (Subject matter 320) ``audit materiality'' the definition of materiality is (with reference to IASC's ``Framework for the preparation and presentation of financial statements'', para. 30) as follows:

Information is material if its omission or misstatement could influence the economic decision of use point rather than being a primary qualitative characteristic which information must have if it is to be useful.

users of financial statements. In both cases, materiality must be ``measured'' in relation to the ``true and fair view'' that the financial statement must give. What is true and fair, including what is material or immaterial, is determined by the economic decisions which users make on the basis of the financial statements. If decisions are influenced by one or more errors or omissions, they are material, and if not, they are immaterial. There are many different groups of users, including the general public. The auditor must take reasonable account of them all. Most auditing firms use guidelines for determining a starting point for their assessment of the overall materiality in the financial statement. The paradox of materiality is that it is the auditor who assesses what is material or immaterial for users of financial statements. But does the auditor really know what users regard as material or immaterial? Numerous studies and articles have dealt with the concept of materiality. Many of them express a lack of concensus between participants in one group and between this group and other groups of users, preparers and auditors of financial statements. In the study of Robinson and Fertuck (1985) the participants were financial executives and auditors. The participants in Woolsey's (1973a, b), Dyer's (1975), Patillo's (1976) and Rosen's (1982) studies were financial executives, bankers, financial analysts, academics and auditors. Of those, we have got most inspiration from Dyer, Patillo and Woolsey, whose studies come close to real life situations, or have a great amount of external validity. Cases in other studies, not mentioned above, present not all relevant information about the case companies (but only few of them). These studies/cases therefore run the risk of departing from the financial statements users' real life.

Differences between the two groups (auditor and financial analyst) and average materiality levels

Danish accounting legislation makes no mention of materiality as an overall principle in an accounting context, only in connection with specific items. In Denmark, materiality is often confused with the concept of relevance, but the two terms should be regarded separately, since they mean different things. Materiality only makes sense in connection with relevant information, not irrelevant information. While materiality is the same in accounting as in auditing, it has a different meaning for auditors' tasks than for those of

A comparison of the groups reveals that, overall, the auditors' average materiality levels for all four companies (Carlsberg, Micro Matic, B&O, and DDT) are about 60 percent higher for overestimations than those of the financial analysts, and 36 percent for underestimations (refer to Appendix, Table AI). The differences appear especially in the profit-companies, where the auditors average levels for overestimation were 88 percent and 129 percent higher than the financial analysts' overestimation, and for underestimation 70 percent and 107 percent

[ 521 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

higher. In the losing concerns there was a better correspondence between the groups. This seems to confirm that the two groups in Denmark have no knowledge of each others' materiality levels. These results do not correspond to those of Patillo (1976). In his findings the average materiality levels for financial analysts was 4.9 percent of net income, and the auditors were 4.8 percent. Patillo's findings indicate a high degree of agreement. The difference between Patillo's results and this study is probably caused by national differences.

infinite number of rules for assessing materiality would not be able to take account of all situations. These provisional guidelines should therefore be made more concrete by supplementing them with examples (from surveys, for example) of how the frameworks for materiality levels can be established in different concrete situations and in different concrete companies. These examples will not be able to cover all situations, of course, but they can help determine some normative levels.

4. Proposed solutions to the problem

Overall considerations

Expectation gaps are, amongst other things, due to inadequate auditing standards and a lack of acceptance of these standards, together with unreasonable expectations of auditors among users of financial statements and the general public. These two elements can be influenced via dialogues. The procedures outlined below should be implemented successively, and in the order mentioned, over a period of several years. The general idea is, as far as possible, to base solutions on continuous dialogues between the interested parties with the aim of achieving as much consensus as possible.

Dialogues with primary users of financial statements about standards for materiality in financial statements

Establishing standards for materiality among auditors

The survey's conclusions appear to indicate the need for standards, at least for auditors, in order to ensure a degree of uniformity. In order to establish common standards for auditors, a Committee for Auditing Standards should be appointed by the Association of State Authorized Public Accountants in Denmark (FSR) to draw up common guidelines. Every financial statement is unique and individual in the sense that it sends its own signals about a concrete firm. The form is (or can be) the same for most firms, but information that is very relevant and material in one financial statement can be relevant but immaterial in another, while in a third both irrelevant and immaterial. The information which the user of a financial statement seeks about one firm can therefore be very different from what is sought about another firm. As a result of this difference, the materiality levels users employ can be related to different items in different financial statements, just as absolute items are assigned different weights. Thus, even an

The guidelines drawn up by auditors should then be discussed in structured dialogues with the primary user groups. A starting point for this can be FSR's Committee for Auditing Standards in Denmark, with representatives from the primary user groups and public authorities. Such a committee or panel should, of course, fully inform all parties about its work, and hold hearings, seminars, etc. with contributions from different sides. The aim of this is to include as many informed views as possible. The task of the committee will be, on the basis of the provisional guidelines proposed by the auditors, to draw up ``the'' standards that can win the most support. In view of the results, in order to achieve such a consensus, or even to achieve acceptance, several of the groups will probably have to ``shift'' their position first. The dialogues should result in a description of those guidelines on which agreement has been reached in the form of a discussion paper with examples, and later in the form of a statement on auditing standards. This approach will ensure that the criteria in the statement on auditing standards conform to the expectations/demands of the primary user groups.

Disclosure of materiality levels in the ``engagement letter''

After a degree of consensus has been reached between auditors and the primary user groups, the auditor should be required to disclose, and give reasons for, his materiality levels in the engagement letter to the board. In other words, the materiality levels can be included as part of the agreement between firm and auditor. This can be done in the form of a statement on auditing standards. Apart from the engagement letter, the information can also be used in connection with making an offer for the audit, of course.

[ 522 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

In this way, the board will get factual information about the precision of the auditor's work, and ``unrealistic'' expectations among board members can be adjusted. The dialogues this information can give rise to will probably mean that the provisional guidelines will have to be adjusted, and thus be made permanent at a later date.

Disclosure of materiality levels in the audit report

Once that the auditor's materiality levels are known to the board, and once, after dialogues with primary user groups, there is a general guideline setting out which criteria the materiality levels should be based on, a logical next step would be for the auditor to also inform users of financial statements in his report which specific materiality levels he has used. Since the firm discloses the principles on which a concrete financial statement has been drawn up, it only seems reasonable for the auditor to disclose the principles his audit is based on. As far as accounting principles are concerned, the firm can, within the limits of the law, choose those practices it regards as being best suited to its needs. Users can then base their views of the financial statement on the published accounting practice. Similarly, users can consider audit precision on the basis of information about the audit, including the materiality levels used, in the auditor's report. The advantage for the auditor is that he can no longer be held responsible for an unknown error under his own materiality level, since everybody now knows the level, even though some may disagree with it. There is still a risk of unknown material errors (the audit risk) in the financial statement, of course. In the USA, Fisher (1990) has studied the effect of whether or not auditors disclose their materiality levels in an experimental market setting. She concludes that information on materiality levels is relevant to share dealers, and that it results in a more efficient market. The requirement of information about materiality levels in the auditor's report can be incorporated into audit report regulations and in auditing standards on the auditor's report, so that, to start with, it is made voluntary by the regulation first coming into effect after, say, three years. This should rule out misunderstandings, though there can still be disagreement about the size of the materiality level. The not inconsiderable difference is, however, that the disagreement is now ``out in the open'', which means that it can be discussed and taken into

consideration, whether at the annual general meeting or through interested parties' direct enquiries to the firm. If the materiality levels are disclosed in the auditor's report, the importance of the guidelines will probably be somewhat reduced because they are general and the information in the report is specific. And if users know the actual levels, they can be assumed to be not greatly interested in knowing how the auditor has arrived at them. One consequence of disclosing the materiality levels in the auditor's report, of course, will be that there must be no doubt that all known errors have been corrected. If they have not been corrected, the user will have doubts about whether the financial statements actually contain known errors near the materiality level. This uncertainty can be eliminated by a legal requirement for all known errors to be corrected, and, if necessary, that the firm should positively state that this has been done. If this suggestion is not adopted, the uncertainty must be eliminated in another way. For example, by the auditor stating in his report, after the disclosure of the materiality level, that all known errors, apart from petty errors, have been corrected. The purpose of the above-mentioned proposals is, of course, to help establish a greater degree of consensus between society's expectations (including users of financial statements) of auditors and its opinion of auditors' performance on the one hand, and the concept of generally accepted auditing standards, as laid down in the current statement of auditing standards, on the other. This can be achieved by attitudes on both sides being influenced. For example, the dialogues can result in the elimination of unreasonable expectations of auditors, including those that are too costly to fulfill. The dialogues can also help reconcile generally accepted auditing standards (and thus auditors' performance) with users' expectations by means of guidelines in the area. Or reduce, and perhaps eliminate, the expectation gap, since, in principle, expectation gaps should not result from inadequate/out-of-date guidelines, but solely from isolated cases of inadequate work from individual auditors. A study carried out in New Zealand by Porter (1993) shows that 34 percent of the reasons for the expectation gap between auditors and society, including users of financial statements, were due to unreasonable expectations of the auditors, 50 percent to inadequate guidelines, and only 16 percent to inadequate work from the auditors.

[ 523 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

According to these results, dialogues and standards could help reduce a huge 84 percent of the expectation gap (in New Zealand), which is quite remarkable. And there is no reason to think that things are different in the rest of the world. The aim and goal of these proposals has been to eliminate, or at least reduce, the general or abstract and often not understandable content of materiality, and instead relate materiality assessments and levels to something concrete in the financial statement, to the benefit of both auditors and users of financial statements.

Reducing the expectation gap by way of limiting liability language in engagement letters

Engagement letters are tools that are used to manage client's expectations. One of its fundamental benefits is that it clearly defines the scope of the job and has the mutual agreement of the accountants and the clients. Engagement letters are able to close the expectation gap concerning who is responsible and who will pay in liability settlements. Camico Mutual Insurance Company, recommends the use of limiting liability language in engagement letters where the risk-versus-reward scale is not appropriately balanced. Limiting liability language is recommended on jobs in which the risk is high compared to the reward. For example, Y2K consulting obviously was a situation that needed the use of such language. The types of engagements appear more often today as accountants take up more assignments involving high technology and investment advising, in which the risks are less predictable than in more traditional services. One Camico member recently evaluated a client's entire accounting system, in which he would purchase, install, and test new accounting software. He was worried about the likelihood for liability problems if the new system developed major glitches, so he included the following limiting liability language in the engagement letter:

As we discussed, our essential fees in this engagement are very small compared to the amount of business that will be processed by your new accounting system. Accordingly, our liability to you in the event of any defects in the system will be limited to the lesser of our fees for this engagement, or the cost to repair any defects in the accounting system that we may have caused.

unintimidating enough to not provoke a client's reservations about lengthy or ``tricky'' legalese. Second, it clearly states the area of concern (in this case the new accounting software system). Third, it provides a detailed explanation of the accountant's liability if there are major problems with the system. Finally, it recognizes that problems could be caused by the accounting firm. Such language is more likely to be accepted in court than other form of disclaimers that seek to avoid responsibility in areas where the accountant is actually negligent. Despite its value, there are disadvantages to the use of limiting liability language. It does not limit liability to any third parties in a lawsuit and it is not enforceable in every court. In addition, some clients might be offended, which may lead to loss of business. However, Camico believes that, particularly in high risk/lower reward jobs, the advantages of limiting liability language far offset the disadvantages. Advantages can be seen during the assessment stage, by encouraging the accountant to assess risks versus rewards, an essentially valuable exercise. Additionally, discussions and negotiations with the client contribute to an environment of open communication from the start. The communication process can also help identify future clients that are totally nonflexible in sharing liability risks. This type of client one may be better off without. Most notably, limiting liability language can be an important reference point in settlement negotiations. As to whether such language will have any grounds in court, this will vary from state to state and court to court. Currently, such decisions are being made on a case-by-case basis. On the other hand, the simple act of communicating with the prospective client and coming to a mutual agreement that is formally documented is a positive step toward limiting liability. In short, a few short, clearly written sentences that state the risk, describe the appropriate liability, and acknowledge responsibility for potential negligence may significantly reduce settlement fees.

Reduction of expectation gap through unqualified opinion expressed by auditors

This language shows a number of key characteristics of effective limiting liability language. First, it is short and

To reduce the expectation gap, the auditors have to exercise reasonable skill, care and maintain their professional independence in issuing unqualified opinion regarding true and fair view of a client's financial statement. This is to ensure that the auditors do not provide any misleading information that will

[ 524 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

provide a false perception to the public. An auditor should not issue an unqualified opinion unless the best judgment is that the financial statements are free of misstatements resulting from management fraud. In the Malaysia context, MIA By-Law A-2 Integrity and Objectivity states that all members of the accounting profession have to be fair, intellectually honest and free of conflicts of interest. In fact, the MIA By-Law even specifically states that members shall be fair in their approach to their professional work and shall not allow any prejudice, bias or influences of others to override their objectivity. Thus, if the auditors are unable to maintain their professional independence in carrying out their audit work, an unqualified opinion on the client's financial position should not be issued. Otherwise the audit report will not be based on the true judgment of the financial position of the client. In the public practice, members may in the course of their professional work, be exposed to situations which involve the possibility of pressures being exerted on them. These pressures may impair their objectivity. Hence, members shall identify and assess such situations and ensure that they uphold the principles of integrity and objectivity in their professional work at all times. Members shall neither accept nor offer gifts or entertainment which might reasonably be believed to have a significant and improper influence on their professional judgment or those with whom they deal, and shall avoid circumstances which would bring their professional standing or the institute into disrepute. A member in public practice shall be, and be seen to be, free in each professional assignment he undertakes, of any interest which might detract from objectivity. The fact that this is self-evident in the exercise of the reporting function must not obscure its relevance in respect of other professional work. Although a member not in public practice may be unable to be, or be seen to be, free of any interest which might conflict with a proper approach to his professional work, this does not diminish his duty of integrity and objectivity in relation to that work. The auditor should resign from performing that audit task and may advise the client to hire others who are competent to perform the work (Audit Commission, www.cipfa.org). If the client involved in any criminal activities which might threatened the safety of the public, MIA By-Law A-5: Confidentiality states that the auditor has the legal right or duty to disclose such fact in the qualified opinion expressed in the audit report to warn the public of such incidence.

Creating an independent agency to oversee audit regulation

The government could play an important role in reducing the expectation gap by creating an independent agency to oversee the audit regulation. To investigate stakeholder perceptions of the structure and function of such an agency, three models were developed: an Auditing Council; a Commission for Audit; and a Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Auditing Council would be a private body analogous to the Financial Reporting Council. Commission for Audit would be a public sector body analogous to the Audit Commission for local and health authorities in England and Wales. A SEC would be a public sector body with overall responsibility for City regulation, including that of listed company audit An Auditing Council received the most support, a Commission for Audit the least, with a UK SEC provoking the strongest reactions both for and against. Currently, arguments in favor of increased regulation were generally framed in terms of increased openness that would ``materially enhance the credibility of audits''; arguments against expressed fears that it would be ``cumbersome'' and add a ``further tier of bureaucracy''. Overall, there was a significant degree of support to make the case for establishing an independent regulatory body. The structure of the independent body should match the expectation gap's main components as revealed by the study: independence, monitoring and discipline. Such a body might be called a Listed Companies Audit Board (LACB), structured into three panels of responsibility: an auditor independence panel; an audit quality panel; and a disciplinary panel. An auditor independence panel's role would be to set up to monitor independence standards and guidelines, for example by restricting non-audit services in whole or in part, or by setting up procedures formally to authorized provision of non-audit services. It can be argued that providing audit services should be remunerative in itself and not conditional, or perceived as conditional, on the auditor providing non-audit services. The role of an audit quality panel would be to set up and maintain a register of auditors whom the panel recognized as capable of undertaking listed company work, and to monitor the quality of audit work done. A possible consequence of such a licensing procedure is that it might lead to increased competition for listed company audits. These are increasingly dominated by the Big Four firms, partly because of the reputation effect.

[ 525 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

External validation procedures might allow other firms to join the register and compete against the Big Four, especially for the audit of middle or lower-ranking listed companies, where the importance of global reach is less significant. Failure to observe standards of auditor independence and quality, and ignoring guidelines, would result in referral to a disciplinary panel. Sanctions against a firm, a firm's office or a partner might include ``naming and shaming'', fines, or removal from the register of listed company auditors.

Going concern reporting developments for standard setters

According to Monroe and Woodliff (1994) they have formally defined the expectations gap as the difference between the beliefs of auditors and the public about the duties and responsibilities assumed by the auditor, and the message conveyed by the audit report. One key purpose of financial statements is to foster the optimal allocation of investing capital between competing uses by providing all material, relevant information to the user community. The purpose of the audit report is to reveal the auditor's success in verifying the financial statement assertions. Thus, it is dismaying to find differences between the auditors' definition of their responsibilities and that of the user community. Accordingly, the expectations gap has prompted many questions about audit quality in general and, in particular, the auditor's ability to make judgments in the presence of going concern uncertainties. This gap has led to the issuance of new standards in many countries. For example, in the USA, Statement of Auditing Standards (SAS) No. 59 entitled ``Auditors' consideration of an entity's ability to continue as a going concern'' (AICPA, 1989) was issued to help reduce the expectations gap. The Australian Auditing Standards Board issued AUS 708, entitled ``Going concern'' (AASB, 1996). The UK issued SAS 130 entitled ``Going concern'', to accomplish similar objectives (APB 1996). Financial statement users have stated that the type of report issued is an important element in their investing and credit-granting decisions (AICPA, 1982). Therefore, inaccurate reporting can result in suboptimal investment and credit decisions. The resulting misallocation of capital slows economic and productivity growth. This situation arose because, initially, auditors were not required to search for indicators of going concern problems. Financial statement users, on the other hand, expected auditors to search for and report on uncertainties that could threaten

that company's ability to survive. The US Auditing Standards Board's (ASB) deliberations led to the issuance of SAS No. 58, which addressed all uncertainties, and SAS No. 59, which had particular reference to going concern uncertainties. A major purpose of these standards was to enhance the auditors' reporting responsibilities in order to remedy the financial statement users' complaints. In the USA, the goal of Auditing Standard Board (ASB) was to reduce the expectations gap in audit reports on uncertainties. Most studies indicate that investors do depend on audit reports to highlight significant uncertainties. Nevertheless, published research indicates that many companies receive clean reports prior to filing for bankruptcy. Users have frequently asked the question, ``If an audit report cannot provide an early warning signal of impending business failure, what good is it?'' (Carmichael and Pany, 1993). From the financial statement's users' perspective, the new form of going concern report should sends a clear and unambiguous signal to them. But from the perspective of auditors, with the new standard, they are more likely to modify reports for distressed companies in accordance with users' expectations (Carmichael and Pany, 1993). The auditor should be required to evaluate whether there is ``substantial doubt'' about the client's ability to continue as a going concern in every audit. They are asked to obey the following: . Detection. The auditor now has an obligation to make an assessment at the conclusion of the audit of the client's ability to continue as a going concern. . Time period. The focus of the auditor's assessment of the client's ability to continue as a going concern is now tied to a ``reasonable'' time period of one year. . Evaluation. Previously, the decision to modify the audit report hinged on recoverability of the assets, and recognition and classification of liabilities. Now going concern status is a separate issue. . Reporting. The ``subject to'' qualification should be supplanted by an explanatory paragraph for all material uncertainties including going concern uncertainties. The major objectives of the new standards were to improve communication to financial statement users, and to ensure that auditors made an affirmative effort to evaluate and report on each client's going concern status. This will not only lead to addressing the issue of auditor reputation and credibility, but it also ensures useful, clear and unambiguous financial statements to the user community.

[ 526 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

The effect of education on reducing the expectation gap concerning perceptions of messages conveyed by audit and review reports

The audit expectation gap has been described by Humphrey et al. (1992) as the gap between the public's perception of the role of the audit and the auditor's perception of that role. The expectation gap still continues to persist, not only with respect to naive users, but also with respect to sophisticated users of general purpose financial reports. Thus, efforts must be doubled by the profession in its attempt to narrow the expectation gap. According to the Middleton Report, it recognized that education is vital to help contain the expectation gap. This view is supported by Jenkins (1990) who indicated that the profession needs a continuing, imaginative program of explaining the inherent limitations in accounting, reporting and auditing to the users of accounts. Also, Smithers (1992) stated that he believes that an education process would have to form a major part of any campaign aimed at closing the expectation gap. Monroe and Woodliff (1994) found that auditing students' beliefs about auditors' responsibilities, the reliability of audited financial information and future prospects changed significantly over the semester. They concluded that education is an effective approach to address the expectation gap. Ferguson et al. (2000) found that Canadian co-operative students had pre-scores on an expectation gap instrument that are closer to practicing auditors relative to the pre-scores of Australian non-co-operative students, which they attributed to experience. There were significant differences between auditors and students who had not completed an auditing course, about auditors' responsibilities, the reliability of audited financial information and the decision usefulness of audited or reviewed financial statements. After completing their course, the auditing students believed auditors assumed less responsibility for soundness of internal control, maintaining accounting records, preventing fraud and detecting fraud; management assumed more responsibility for producing financial statements; the auditor/ reviewer was more independent; and the auditor/reviewer exercised more judgment in the selection of procedures, than they did at the beginning of the course. These changes were in the direction of auditors' beliefs indicating a significant reduction in expectation gap in relation to auditor's or reviewer's responsibilities. After finishing the auditing course, students believed to a greater extent that the auditor

agreed with the accounting policies and to a lesser extent that the entity was free from fraud. These changes were in the direction of auditors' beliefs indicating a significant reduction in the expectation gap in relation to the reliability of audited or reviewed financial statements. However, the auditors still had a significantly stronger belief that the audited financial statements give a true and fair view and believed a significantly higher level of assurance was provided by the audit. All groups believed that an audit provided a higher level of assurance that there were no material errors than a review. After the auditing course, students believed to a greater extent that reviewed financial statements were useful for monitoring performance and making decisions. These changes were in the direction of auditors' beliefs indicating a significant reduction in the expectation gap in relation to the usefulness of reviewed financial statements. However, the students still believed that the unqualified audit/review report meant that the entity was well managed. The results indicate that education may be an effective way to reduce the expectation gap. However, several differences in expectations still existed. Also, it must be remembered that it may not be practical to expect all parties to the expectation gap to undertake the equivalent of an undergraduate auditing course. However, it emphasizes the importance of the accounting bodies retaining auditing as a prescribed subject for accreditation purposes for undergraduate tertiary degrees, to help ensure that members of the accounting profession do not have misconceptions about the audit function.

5. Conclusion

The collapse of Enron and WorldCom raise a number of issues that have a direct bearing on the expectation gap. Public debate of these collapses has centered on issues of: . corporate governance and management style, management neglect or misconduct as is evident by recent ASIC enforcement actions against executives and directors of a number of collapsed companies; . mandatory audit committees, their role, structure, composition and operation, management representations to such committees; . the independence of the auditor, the provision of non-audit services, the rotation of auditors, attendance of auditors at AGMs and ex-auditors serving on the boards of companies which are audited by the same auditor;

[ 527 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

the need to reassess the effectiveness of the audit process, including existing auditing standards, as well as providing them with the force of law; the need to monitor the effectiveness of legislation, regulations and regulatory bodies particularly with regard to specialised industries; the need to review current accounting standards, the standard setting process and the adoption of international accounting standards on a wholesale or unconditional basis; the need to reassess the financial reporting framework, strengthening continuous reporting requirements with adequate sanctions for non-compliance; the need to reassess the role and responsibilities of the CEO and corporate whistleblowing expectations including the strengthening of current reporting obligations of auditors to regulators; and the need to assess the effectiveness of the co-regulatory framework for the profession and the ability of the profession to maintain quality and effectively sanction or discipline members when required to do so.

communications: with large investors and government, presenting the corporation's public face, etc. The CEO attends to executive and operational aspects coordinating the work of other executive directors and running the company internally. This separation is a common UK model whereas the USA model tends to position one person in a combined role.

References

In dealing with the above issues the professional accounting bodies need to be vigilant and proactive, working closely with other professional bodies and regulators to ensure that similar consequences are not repeated in the future. The movement to more democratic forms of corporate governance by empowering owners is important not only for creating wealth; it cuts directly to our ability to maintain a free society. It may be an exaggeration but ``Corporations determine far more than any other institution the air we breathe, the quality of the water we drink, even where we live''. However, they are not accountable to anyone. The Cadbury Report (Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance) was published in December 1992 with a further Financial Reporting Council study in June 1995. The former reported on the ``propriety'' of corporate governance particularly public quoted companies. It argued for:

. . . clearly accepted division of responsibilities at the head of a company, which will ensure a balance of power and authority, such that no individual has unfettered powers of decision.

This reflects UK practice historically where the chief executive's and chairman's position are held by two people. The chairman chairs the board and oversees external

AASB (1996), An Experimental Investigation of Alternative Going Concern Reporting Formats: Canadian Experience, Anandarajan, A, School of Management, New Jersey Institute of Technology, University Heights, Newark, NJ. AICPA (1982), ``Serving the public interest: a new conceptual framework for auditor independence'', report prepared on behalf of the AICPA in connection with the presentation to the Independence Standards Board of Serving the Public Interest, AICPA, October 20. AICPA (1989), Bankcruptcy Prediction Models and Going Concern Audit Opinions Before and After SAS, No. 59. AICPA (1996), Auditing Procedures Study, Audit Sampling, AICPA, New York, NY. APB (1996), ``The company applies APB Opinion No. . . . that no warranty reserve was necessary as of December 31, 1995 and 1996'', Leinenger Audit Report, 1995, 1996. Carmichael, D.R. and Pany, S.G. (1993), ``The appearance standard for auditor independence: what we know and should know'', in International Research Implications for Academicians and Standard Setters on Going Concern Reporting: Evidence from the United States, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. COSO Report (1982), December. Dyer, J.L. (1975), ``Toward the development of objective materiality norms'', The Arthur Andersen Chronicle, October. Ferguson, C.B., Richardson, G.D. and Wines, G. (2000), ``Audit education and training: the effect of formal studies and work experience'', Accounting Horizon, June, Vol. 14 No. 2, pp. 137-67. Fisher, M.H. (1990), ``The effects of reporting auditor materiality levels publicly, privately, or not at all in an experimental markets setting'', Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 9, Supplement. Grice, J.S. Sr (1989), Bankruptcy Prediction Models and Going Concern Audit Opinions, Before and After SAS, AICPA, New York, NY, No. 59 Humphrey, C., Moizer, P. and Turley S. (1992), ``The audit expectation gap plus ca change, plus c'est la meme chose?'', Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 3, May, pp. s137-61. IASC (1995), Framework for the Preparation and Presentation of Financial Statements, FSR, Copenhagen. Jenkins, W.P. (1990), ``The goal of price stability'', Taking Aim: The Debate on Zero Inflation,

[ 528 ]

Junaid M. Shaikh and Mohammad Talha Credibility and expectation gap in reporting on uncertainties Managerial Auditing Journal 18/6/7 [2003] 517-529

Policy Study No. 10, C.D. Howe Institute, Toronto, pp. 19-24. McEnroe, J.E. and Martens, S.C. (2002), Taxman, March 9, pp. 236-51. Marian, Y.J., Gladie, M.C. and Albert, Y.H. (2002), Malayan Law Journal, Vol. 1. Mautz, R. and Sharaf, H. (1961), The Philosophy of Auditing, American Accounting Association, Sarasota, FL, ch. 9. Monroe, G. and Woodliff, D. (1994), ``The audit expectation gap: messages communicated through the unqualified audit report'', Perspectives on Contemporary Auditing, pp. 47-56. Murray, A. (2002), July 2. Orrenstein, P. (1995), ``Jenkins on the Jenkins Report'', CA Magazine, April, pp. 15-18. Patillo, J.W. (1976), The Concept of Materiality in Financial Reporting, Financial Executive Research Foundation, New York, NY. Porter, B. (1993), ``An empirical study of the audit expectation-performance gap'', Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 24 No. 93. Robinson, C. and Fertuck, L. (1985), Materiality. An Empirical Study of Actual Auditors Decisions, Research Monograph No. 12, The Canadian Certified General Accountants' Research Foundation, Vancouver. Rosen, L.S. (1982), An Empirical Study of Materiality Judgements by Auditors, Bankers, and Analysts. Research to Support Standard Setting in Financial Accounting: A Canadian Perspective, The Clarkson Gordon Foundation, Toronto. Smithers (1992), ``Legislative Session: 1st Session, 35th Parliament'', Hansard, Vol. 3, May 12. Walker, D. (2002), March 2. Woolsey, S.M. (1973a), ``Approach to solving the materiality problem'', Journal of Accountancy, March. Woolsey, S.M. (1973b), ``Materiality survey'', Journal of Accountancy, September.

Further reading

Chapman, P. (2001), ``Corporate governance and the sons of Cadbury'', Management Accounting Journal, Vol. 1 No. 4. Danish Accounting Standards (1994), FSR, Copenhagen. Danish Auditing Standards (1996), FSR, Copenhagen (Danish edition only).

Elliott, R.K. (1981), ``Audit materiality and myth'', D.R. Scott Memorial Lectures in Accountancy, Vol. 11. Elliott, R.K. (1983), ``Unique audit methods: Peat Marwick International'', Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, Vol. 2 No. 2, Spring. FASB (1975), Discussion Memorandum: An Analysis of the Issues Related to Criteria for Determining Materiality, 21 March. Laing, D. and Weir, C.M. (1999), ``Governance structures, size and corporate performance in UK firms'', Management Decision,Vol. 37 No. 5, pp. 457-64. Glautier, M. and Underdown, B. (1997), Accounting Theory and Practice, 6th ed., Pitman, London. Godfrey, J., Hodgson, A. and Homes, S. (1997), Accounting Theory, 3rd ed., John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. Hjskov, L. (n.d.), ``Should errors in financial statements be corrected?'', unpublished working paper. ISA (1994), International Standards on Auditing No. 320 and Glossary of Terms, International Auditing Practices Committee (IAPC), issued by the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), July, FSR, Copenhagen. Leslie, D.A. (1985), Materiality, CICA, Toronto. Public Sector Corporate Governance (2002), ``Turnbull report'', Credit Control, Vol. 23 No. 1, pp. 27-30. Ricchiute, D. (1992), Auditing, South-Western Thomson Learning, Mason, OH. Schelluch, P. and Green, W. (1996), ``The expectation gap: the next step'', Australian Accounting Review, Vol. 6 No. 2. Selley, D.C. (184), ``The origins and development of materiality as an audit concept'', paper presented at the Audit Symposium VII, Touche Ross/University of Kansas Symposium on Auditing Problems. Vinten, G. (2002), ``The corporate governance lessons of Enron'', Corporate Governance, Vol. 2 No. 4, pp. 4-9. Wilson, I. (2000), ``The new rules: `ethics and social responsibility''', Strategy and Leadership, Vol. 28 No. 3, pp. 12-16. Wolk, H. and Tearney, M. (1997), Accounting Theory, 4th ed., Thomson, Mason, OH.

Appendix

Table AI Comparison of the auditors' and the financial analysts' average levels Index figures for auditors' average levels (average of financial analysts = 100) Levels in the cases Overestimation Underestimation Company 1: Company 2: Company 3: Company 4: Carlsberg Micro Matic B&O DDT 188 170 229 207 124 (15012) 66 94 102 Average 159 (157) 136

Source: Research in Accounting Conference Proceeding, Japan, 1998

[ 529 ]

Вам также может понравиться

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- A New Look at Management AccountingДокумент14 страницA New Look at Management AccountingWan LingОценок пока нет

- StudentДокумент1 страницаStudentWan LingОценок пока нет

- 动物Документ12 страниц动物Wan LingОценок пока нет

- MPWДокумент9 страницMPWWan LingОценок пока нет

- Teleological Moral SystemДокумент4 страницыTeleological Moral SystemWan LingОценок пока нет

- RR +F F Aih I+ Er Ii: R RR !aslf, E G$igДокумент14 страницRR +F F Aih I+ Er Ii: R RR !aslf, E G$igWan LingОценок пока нет

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Fae3e SM ch04 060914Документ23 страницыFae3e SM ch04 060914JarkeeОценок пока нет

- Suggested Solutions/ Answers Fall 2016 Examinations 1 of 8: Business Taxation (G5) - Graduation LevelДокумент8 страницSuggested Solutions/ Answers Fall 2016 Examinations 1 of 8: Business Taxation (G5) - Graduation LevelQadirОценок пока нет

- CipherДокумент2 страницыCipherAnonymous RXEhFb100% (1)

- Vault Career Guide To Investment ManagementДокумент121 страницаVault Career Guide To Investment Managementsoolianggary100% (4)

- HedgingДокумент7 страницHedgingSachIn JainОценок пока нет

- Murex Training at Analyst360Документ13 страницMurex Training at Analyst360AnalystОценок пока нет

- Macro FinalДокумент198 страницMacro FinalpitimayОценок пока нет

- Notes The Men Who Built AmericaДокумент6 страницNotes The Men Who Built Americaapi-299132637Оценок пока нет

- Popularity of Credit Cards Issued by Different BanksДокумент25 страницPopularity of Credit Cards Issued by Different BanksNaveed Karim Baksh75% (8)

- Financial Accounting-Short Answers Revision NotesДокумент26 страницFinancial Accounting-Short Answers Revision Notesfathimathabasum100% (7)

- Manufacturing Accounts - Principles of AccountingДокумент6 страницManufacturing Accounts - Principles of AccountingAbdulla Maseeh100% (1)

- IIFL Nifty ETF PresentationДокумент25 страницIIFL Nifty ETF Presentationrkdgr87880Оценок пока нет

- Lenskart - Marketing ProjectДокумент27 страницLenskart - Marketing Projectaditya bandil0% (2)

- Gorin Business Structuring MaterialsДокумент1 260 страницGorin Business Structuring MaterialsJoshua Friel100% (3)

- Investment Vs SpeculationДокумент8 страницInvestment Vs Speculationshehbaz_khanna28Оценок пока нет

- Carter Favorite Set UpsДокумент56 страницCarter Favorite Set UpsAndreas100% (2)

- FMA Sues Akin GumpДокумент67 страницFMA Sues Akin GumpDomainNameWireОценок пока нет

- Banking and Finance Subject Code Subjects L T P CДокумент10 страницBanking and Finance Subject Code Subjects L T P Cshanti priyaОценок пока нет

- The Wall Street Journal - 2019-09-21 PDFДокумент54 страницыThe Wall Street Journal - 2019-09-21 PDFKevin MillánОценок пока нет

- 144MW Hydropower Development Opportunity in Mufindi, TanzaniaДокумент2 страницы144MW Hydropower Development Opportunity in Mufindi, TanzaniagadielОценок пока нет

- Annual Shareholders' Meeting - 04.18.2016 - MinutesДокумент11 страницAnnual Shareholders' Meeting - 04.18.2016 - MinutesBVMF_RIОценок пока нет

- Sherkhan ProjectДокумент96 страницSherkhan ProjectAbhishek AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Lecture 5.2-General Cost Classifications (Problem 2)Документ2 страницыLecture 5.2-General Cost Classifications (Problem 2)Nazmul-Hassan Sumon75% (4)

- Say's LawДокумент10 страницSay's Lawbrook denisonОценок пока нет

- API 571 Damage Mechanism Affecting Fixed Refining EquipmentsДокумент4 страницыAPI 571 Damage Mechanism Affecting Fixed Refining EquipmentsKmt_AeОценок пока нет

- Lacerta Abs Cdo 2006 1 LTD ProspectusДокумент215 страницLacerta Abs Cdo 2006 1 LTD ProspectusDuff ChampОценок пока нет

- Feshbach On ShortingДокумент3 страницыFeshbach On ShortingLincM@TheMinorGroupcomОценок пока нет

- TurnKey Investing With Lease-Options (Table of Contents, Intro, Chapter 1)Документ35 страницTurnKey Investing With Lease-Options (Table of Contents, Intro, Chapter 1)Matthew S. ChanОценок пока нет

- Genmath e PortfolioДокумент17 страницGenmath e Portfoliosalazar sagaОценок пока нет

- All 1Документ7 страницAll 1Sudhanshu SrivastavaОценок пока нет