Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

County Shredding Response

Загружено:

tulocalpoliticsОригинальное название

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

County Shredding Response

Загружено:

tulocalpoliticsАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ANNE POPE, JANIS GONZALEZ, WANDA WILLINGHAM, GERALDINE

E BELL, SAMUEL COLEMAN and LEE PINCKNEY, Plaintiffs, - against COUNTY OF ALBANY and the ALBANY COUNTY BOARD OF ELECTIONS, Defendants. ____________________ Civil Action #11-CV-736 LEK/DRH DEFENDANTS MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN OPPOSITION TO PLAINTIFFS MOTION FOR DISCOVERY SANCTIONS MURPHY, BURNS, BARBER & MURPHY, LLP Attorneys for Defendant County of Albany 226 Great Oaks Boulevard, Albany, New York, 12203 Telephone: 518-690-0096; Telefax: 518-690-0053 Of Counsel: Peter G. Barber, Esq. Catherine A. Barber, Esq. THOMAS MARCELLE, ESQ. Attorney for Defendant Board of Elections Albany County Attorney, Department of Law 112 State Street, Suite 1010, Albany, New York, 12207 Of Counsel: Karry Culihan, Esq. Adam Giangreco, Esq.

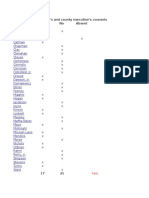

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ........................................................................................................... i PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ......................................................................................................1 STATEMENT OF FACTS ..............................................................................................................1 ARGUMENT ...................................................................................................................................4 POINT I................................................................................................................................4 DEFENDANTS PRESERVED RELEVANT DOCUMENTS................................4 POINT II PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO PROVE CULPABLE CONDUCT ..............................7 A. B. C. D. POINT III DEFENDANTS ACTED IN GOOD FAITH .........................................................14 POINT IV PLAINTIFFS PROPOSED RELIEF IS UNJUSTIFIED ......................................16 CONCLUSION ..............................................................................................................................18 Thomas Scarff, Secretary of Redistricting Commission ..............................8 Hon. Frank Commisso, Majority Leader ...................................................10 Eugenia Condon, Esq., Deputy County Attorney ......................................11 County Executives Office .........................................................................12

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page Anderson v. Sothebys Inc. Severance Plan, 2005 WL 2583715 (S.D.N.Y.) ..................................9 Byrnie v. Town of Cromwell, Bd. Of Educ., 243 F.3d 93 (2nd Cir. 2001) ....................................4 Essenter v. Cumberland Farms, Inc., 2011 WL 124505 (N.D.N.Y. 2011) ....................................15 Favors v. Fisher, 13 F.3d 1235 (8th Cir. 1994) ...............................................................................16 Field Day, LLC v. County of Suffolk, 2010 WL 1286622 (E.D.N.Y.)............................................9 Hamilton v. Mount Sinai Hospital, 528 F.Supp.2d 431 (S.D.N.Y. 2007) .......................................8 Kronisch v. U.S., 150 F.3d 112 (2nd Cir. 1998) ...............................................................................4 Latimore v. Citibank Fed. Sav. Bank, 151 F.3d 712 (7th Cir. 1998) ..............................................16 Marlow v. Chesterfield County School Board, 2010 WL 4393909 (E.D. Va. 2010) ......................9 Orbit One Communciations, Inc. v. Numerex Corp., 271 F.R.D. 429 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) .................7 Pension Plan v. Banc of America Securities, 685 F.Supp.2d 456 (S.D.N.Y. 2010) ........................8 Prestige Global Co. Ltd. v. L.A. Printex Industries, Inc., 2012 WL 1569792 (S.D.N.Y. 2012) ...............................................................................................................................4 Residential Funding Corp. v. DeGeorge Fin. Corp., 306 F.3d 99 (2nd Cir. 2002) .................3, 8, 16 S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co., 695 F.2d 253 (7th Cir. 1982) ................................................................................................................................................9 Steuben Foods, Inc. v. Country Gourmet Foods, LLC, 2011 WL 1549450 (W.D.N.Y. 2011) ..............................................................................................................................................15 Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 220 F.R.D. 212 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) .............................................13

-i-

Statutes, etc. Local Law C of 2011.............................................................................................................. passim NYS Arts & Cultural Affairs Law .................................................................................................13

-ii-

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT Proving nothing, other than a talent to drawing attention by using phrases like knowingly destroyed, and destruction of material evidence, plaintiffs motion is a disservice to this Court. It is similarly easy to paint a false image of defendants discovery responses by mischaracterizing a handful of isolated events. But, when the actual facts and proper law are applied, it is clear that plaintiffs never should have filed this motion. The County discharged its legal obligations in preserving, maintaining, and producing all material evidence relating to the redistricting of its legislature. Given its reckless nature, plaintiffs motion should be summarily denied, with an award of attorneys fees and expenses to defendants. STATEMENT OF FACTS In a Resolution dated January 10, 2011, the Albany County Legislature appointed a seven member Redistricting Commission, with representatives from the Democratic and Republican Parties, to redistrict the Legislature under the 2010 Federal census. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 2. The Legislature apportioned funds for retaining John Merrill, as a consultant on the redistricting process. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 6. Thomas Marcelle, Esq., counsel to the Republican minority, was retained as attorney to assist the Redistricting Commission and the Legislature. Thomas Scarff was appointed Secretary of the Redistricting Commission. Mr. Scarff maintained a website which contained updated information on notices of meeting times and locations, meeting minutes, Federal census numbers, maps, and general 1

information about redistricting. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. C (Scarff Tr. 61:12-18; 68:1769:2). From February 24, 2011, through April 23, 2011, the Redistricting Commission conducted seven public meetings throughout the County. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 12. At many of the meetings, no persons provided public comment. See id. Mr. Scarff hand wrote information about the meeting, including attendance by members and public participation. Mr. Scarff used his reminder notes to prepare minutes that were placed on the website. With that task complete, Mr. Scarff discarded his notes. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. C (Scarff Tr. 67:17-68:16; 115:20-116:13). On May 19, 2011, the Redistricting Commission conducted a public hearing on the proposed redistricting plan. The public hearing was videotaped and transcribed. See Barber Aff. 4. On May 23, 2011, the Legislature held a public hearing on Local Law C of 2011, the redistricting plan recommended by the Redistricting Commission. The public hearing was videotaped and transcribed. At the conclusion of the public hearing, the Legislature approved Local Law C of 2011. See Barber Aff. 4. On May 31, 2011, the County Executive held a public hearing on his consideration of Local Law C. This public hearing was transcribed. See Barber Aff. 5. The County Executive had no role in the preparation of the redistricting map or the Legislatures adoption of Local Law C. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 31:15-21). The County Executives office maintained a to-do list for the County Executives consideration of 2

Local Law C, including copies of documents. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 157:22-158:10). On June 6, 2011, the County Executive signed Local Law C. See Dkt. No. 1 at 17; Dkt. No. 100 at 20. On June 29, 2011, plaintiffs commenced this action under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act contending that Local Law C diluted the vote of the minority community. See Dkt. No. 1. Pursuant to State statute and County policy, the County has preserved all records relating to the redistricting process. As detailed in the accompanying affidavits, defendants have timely preserved all available documents relating to the redistricting process, and upon receipt of plaintiffs demands, have produced responsive documents. In December 2011, the staff of the outgoing County Executive disposed of documents no longer needed under the Countys retention policy. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 33; Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 66:19-22, 83:23-84:2-10). The County Executives Office received guidance from the Albany County Clerks Office on document retention, and destroyed only appropriate documents. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 33; Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 67:19-22). None of the confidential documents were related to the 2011 redistricting process. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 74:15-17).

ARGUMENT In Residential Funding Corp. v. DeGeorge Fin. Corp., 306 F.3d 99, 107 (2nd Cir. 2002), the Second Circuit imposed exacting standards on a partys efforts to impose sanctions for an alleged failure to produce material evidence. The Court held: (1) that the party having control over the evidence had an obligation to preserve it at the time it was destroyed; (2) that the records were destroyed with a culpable state of mind; and (3) that the destroyed evidence was relevant to the party's claim or defense such that a reasonable trier of fact could find that it would support that claim or defense. Id. at 107. See Byrnie v. Town of Cromwell, Bd. of Educ., 243 F.3d 93 (2nd Cir. 2001). As demonstrated below, plaintiffs motion fails to satisfy any requirement. POINT I DEFENDANTS PRESERVED RELEVANT DOCUMENTS Plaintiffs open their flawed argument with the false premise that defendants failed to preserve relevant documents. Relying upon straw man arguments regarding when the obligation to preserve documents first arose1 or whether or when a litigation hold was instituted, plaintiffs argue that the County was derelict in its discovery obligations. Plaintiffs conveniently ignore the fact that the County engaged in a good faith

Plaintiffs erroneously maintain that the mere prospect of litigation triggers the preservation of evidence. This obligation to preserve evidence arises when the party has notice that the evidence is relevant to litigation-most commonly when suit has already been filed . . . . Kronisch v. U.S., 150 F.3d 112, 126 (2nd Cir. 1998); see Prestige Global Co. Ltd. v. L.A. Printex Industries, Inc., 2012 WL 1569792, 3 (S.D.N.Y. 2012). Given the fact that the County preserved and produced all evidence regarding the 2011 redistricting process, plaintiffs arguments are of no moment. 4

preservation and production of documents pertaining to the 2011 redistricting process from its inception. As detailed in the accompanying affidavits, defendants conducted diligent searches, and timely produced voluminous responsive documents, and have not intentionally or improperly destroyed any documents relevant to this action. During the short period between the commencement of this action and the August 3rd preliminary injunction hearing, defendants attorneys conferred with County department heads and agency counsel and gathered all documents relating to the 2011 redistricting process. See Barber Aff. 11. The Countys Department of Information and Technology was also contacted regarding this effort. See Diegel Aff. 2. In Defendants Response to Plaintiffs Request for Production of Documents, dated July 29, 2011, defendants produced all available documents relating to the Redistricting Commission, including minutes, hearing transcripts, and reports, all data used by Mr. Merrill in preparing Local Law C, and two bound volumes of election results provided by defendant Board of Elections. See Barber Aff. Exh. A. After the conclusion of the hearing on plaintiffs motion for preliminary injunction, on August 8, 2011, plaintiffs served 41 subpoenas duces tecum on each of the 39 members of the County Legislature, and other members of the Redistricting Commission. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 25. Plaintiffs also served Plaintiffs Requests for Production of Documents dated August 8, 2011, which were identical to its July 5, 2011 demand. 5

Even though these document demands and subpoenas duces tecum were not authorized by this Courts Orders dated July 1, 2011 and July 22, 2011 regarding disclosure, see Dkt. Nos. 4, 22, and also violated Rule 26(d)(1), defendants attorneys contacted counsel for the majority and minority caucuses and requested that they obtain responsive documents from legislators and Commission members. See Barber Aff. 17. Defendants attorneys again contacted Mr. Scarff to confirm his production of all documents considered by the Redistricting Commission. See id. 18. Defendants counsel again notified certain County department heads that might have responsive documents of the current status of the action and requested that they search for and produce relevant documents in response to plaintiffs latest demands. See Barber Aff. 19. In subsequent phone calls, defendants counsel discussed the status of the production with certain department heads and their attorneys. See id. 19. Over the ensuing months, defendants provided plaintiffs with thousands of pages of documents, including multiple year Federal EEOC filings, and affirmative action complaints, grievances, and civil rights actions dating back decades. See Barber Aff. Exhs. B - I. Defendants also provided copious records regarding prior redistricting actions and election results. See id. 13 & Exh. A. In addition, plaintiffs were allowed to depose agency heads, legislative leaders, and County Executives. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 21 (Michael Breslin, former County Executive); Exh. 7 (Dan McCoy, current County Executive); Exh. 11 (Michael Perrin, Deputy County Executive); Exh. 10 (Frank Commisso, Majority Leader); Exh. 19 (Christine Benedict, Minority Leader); Exh. 18 6

(Robert Conway, Commissioner of Human Resources); Exhs. 28 & 29 (Paula Wilkerson, Director of Affirmative Action); Exh. 9 (Thomas Scarff, Secretary of Redistricting Commission). In sum, defendants discovery responses have been complete. POINT II PLAINTIFFS FAILED TO PROVE CULPABLE CONDUCT Beyond failing to show that defendants failed to preserve material evidence, plaintiffs also fail in their effort to prove culpable conduct. Indeed, plaintiffs assertions of malfeasance by defendants rings hollow and is a disservice to the efforts made by defendants, under an expedited schedule, to provide responsive documents. On prior occasions, this Court has properly rebuffed plaintiffs misplaced attacks on defendants discovery responses. See Dkt. Nos. 77, 89, 112. Moreover, plaintiffs are simply unable to refute the conclusion that defendants comprehensive document responses exceeded all applicable standards. Instead, plaintiffs devote most of their brief to arguing that certain individuals failed to meet their discovery duties. By isolating each persons action, plaintiffs improperly seek to project a distorted picture of defendants efforts and recklessly attack the character of public officials. As succinctly held in Orbit One Communications, Inc. v. Numerex Corp., 271 F.R.D. 429, 441 (S.D.N.Y. 2010), this type of complaint is unwarranted: Because of the likelihood that some data will be lost in virtually any case, there is a real danger that litigation [will] become a gotcha game rather than a full and fair opportunity to air the merits of a dispute. In order to avoid sanctions, parties would be obligated, at best, to document any deletion of data whatsoever in order to prove that it was not relevant or, at worst, to preserve everything. 7

citing Pension Plan v. Banc of America Secur., 685 F.Supp.2d 456, 468 (S.D.N.Y. 2010). Far from satisfying the exacting requirement of culpable conduct required to find fault with defendants discovery responses, see Residential Funding Corp. v. DeGeorge Fin. Corp., 306 F.3d 99, 107 (2nd Cir. 2002), the record demonstrates the opposite and shows that each person assailed by plaintiffs exercised good faith in preserving and gathering information, and that the combined efforts of County officials and their attorneys met legal standards. A. Thomas Scarff, Secretary of Redistricting Commission.

Plaintiffs start their personal attacks by assailing Thomas Scarff, Secretary of the Commission, for discarding his handwritten notes of public meetings. Mr. Scarff recorded members attendance and summarized public comment, if any, with names if provided. He discarded the notes after he used them to prepare minutes which he posted on the Commissions website. Mr. Scarffs actions were proper and do not, in the slightest, constitute culpable conduct. For example, in Hamilton v. Mount Sinai Hospital, 528 F.Supp.2d 431, 444 (S.D.N.Y. 2007), the court held: [I]t is hard to see how the notes were destroyed with a culpable state of mind. The notes were merely the handwritten versions of notes that were then put into typewritten form. In such circumstances, the party destroying the notes would have no reason to think that he or she was destroying notes that would ultimately be useful to any party in the future.

See S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc. v. Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co., 695 F.2d 253, 259 (7th Cir.1982)(no bad faith shown where handwritten notes were typed in the form of a memorandum prior to destruction). Likewise, in Anderson v. Sothebys Inc. Severance Plan, 2005 WL 2583715 *4,5 (S.D.N.Y.), under substantially similar circumstances, the court held: There is insufficient evidence here to establish that [defendant] intentionally destroyed notes of the Committee meetings to prevent plaintiff from obtaining them . . . . [Defendant] testified that she routinely destroyed her handwritten meeting notes after she prepared a typewritten report . . . plaintiff has failed to show relevance and is not entitled to an adverse inference instruction. Similarly, in Field Day, LLC v. County of Suffolk, 2010 WL 1286622 * 8 (E.D.N.Y.), the Court held: With respect to Plaintiffs reliance on [the county employees] testimony that he got rid of handwritten notes regarding the permit, the testimony is that he threw out these handwritten reminder notes once he no longer needed them to remind himself. The import of this testimony is that the notes were thrown out shortly after they were made, most likely before the duty to preserve arose. Plaintiffs have not sustained their burden of demonstrating that [the county employee] . . . failed to preserve his files after the duty to preserve arose. Even assuming there was a written litigation hold, Mr. Scarffs discarding of his own reminder notes still would not support a finding of culpable conduct. Like Marlow v. Chesterfield County School Board, 2010 WL 4393909 *3 (E.D.Va. 2010), the routine destruction of handwritten notes that are summarized in typewritten meeting minutes is no evidence that [employee] made a conscious decision to destroy the notes because of [plaintiffs] forthcoming lawsuit. Thus, it would be unreasonable to expect [employee] to consider the litigation hold when she discarded her handwritten notes, and, accordingly, it cannot be said that she 9

had a culpable state of mind when she did so. Indicative of the specious nature of their accusations, plaintiffs fault Mr. Scarff for not recording the names of public attendees, even though they neither spoke nor asked to be identified in the record. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 12 . Even assuming Mr. Scarff was clairvoyant and could discern the identity of public attendees and their motive for attending, nothing in the law would fault Mr. Scarff for not recording this information. Moreover, public participation, let alone attendance, at the seven public meetings was scant. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 12. Under NYS Public Officers Law 103, public participation at public meetings is not required. See DeSantis v. City of Jamestown, 193 Misc.2d 197 (2002). In any event, at two of the public meetings (March 31, and April 14), there were no members of the public in attendance, and at two other public meetings (February 24 and April 5), no public comment was provided. At two other public meetings (March 24 and April 18), the attendance of members of the public were noted but, unlike the last public meeting (April 23), no members of the public identified themselves. Finally, plaintiffs failed to inform this Court that, on May 23, 2011, the Redistricting Commission held a public hearing which was both transcribed and videotaped. See Barber Aff. 4. In sum, plaintiffs efforts to prove culpable conduct in Mr. Scarffs performance of his secretarial duties fall well short of the mark. B. Hon. Frank Commisso, Majority Leader.

Finding no complaint regarding the other 38 County Legislators, plaintiffs strangely focus on Frank Commisso, Majority Leader of the Legislature, and his alleged 10

improper discarding of handouts at Legislative meetings. See Pl. Mem. at 6. Mr. Commisso testified that he did not use a computer and did not have an e-mail address. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. B (Commisso Tr. 55:17-21). He only received copies of documents handed out to all Legislators at meetings, and, with the conclusion of the vote to approve Local Law C, he disposed of his copies. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. B (Commisso Tr. 35:3-10; 50:3-5). The documents received by Legislators, including Mr. Commisso, have been produced. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. B (Commisso Tr. 35:3-10; 50:3-5). Simply stated, plaintiffs allegations against Mr. Commisso are frivolous. C. Eugenia Condon, Esq., Deputy County Attorney.

Plaintiffs next seek to condemn Eugenia Condon, Esq., an Assistant County Attorney, for not issuing a written litigation hold. See Pl. Mem. at 7, 18-19. Again, plaintiffs arguments rest on a false premise. On June 29, 2011, the day of commencement of this action, this Court held a conference during which the County Attorneys office stated that it would have no involvement with this matter and that the County would retain outside counsel. See Dkt. Minute Entry; Marcelle Aff. 4 & Exh. D (Condon Tr. 35:9-23). Soon thereafter, Mr. Marcelle and Mr. Barber entered their appearances on behalf of defendants. Inasmuch as Ms. Condon did not represent defendants, she was not responsible for any litigation steps or coordinating defendants document collection. To the contrary, Ms. Condon was acting only upon behalf of the Department of Law. Like other agency representatives, she was responding to requests by defendants attorneys to search for and 11

locate documents responsive to plaintiffs demands, including, with regard to the Department of Law, litigation files for civil rights and employment actions. Ms. Condon also assisted with the production of affirmative action complaints handled by the Department of Human Resources. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. D (Condon Tr. 26:12-15; 30:6-31:20). In a very short time, Ms. Condon assisted defendants attorneys in the production of litigation and administrative documents dating back to the 1980s. See Marcelle Aff. 5. Far from the scurrilous accusations of culpable conduct, Ms. Condons actions were exemplary. D. County Executives Office.

Plaintiffs next contend that the County Executive engaged in a shredding party or has a missing file in a flawed effort to suggest that the County Executives office engaged in culpable conduct. Plaintiffs efforts are wrong because no material evidence was destroyed. Indicative of their flawed accusations, plaintiffs simply speculate that the documents might be relevant, but choose to ignore the nature of the documents. For example, plaintiffs contend that the County failed to produce e-mails and other documents submitted by Aaron Mair relating to the redistricting process, including his alternative districting plan. See Pl. Mem. at 11. Of course, the premise is false in light of defendants voluminous production of materials submitted by Mr. Mair. Plaintiffs argument is doubly dubious given the fact that Mr. Mair is one of plaintiffs own experts. Plaintiffs also fail to note that the County provided a list of the documents 12

destroyed, and that every document on that list had no relation to the 2011 redistricting action. These documents included confidential resumes (1994-2011), confidential constituent issues (2005-2011), personnel records (1995-2003), correspondence (20002005), and litigation copies (1998-2011). See Karlan Dec. Exh. 33. In particular, neither litigation copies nor the missing file contained any original documents pertaining to the current litigation or the 2011 redistricting process. See Marcelle Aff. Exh. A (Perrin Tr. 86:9-20; 121:6-122:10; 132:5-133:3). Similarly, under NYS Arts & Cultural Affairs Law 57.25(1), the County Executive was only obligated to retain and have custody of such records for so long as the records are needed for the conduct of the business of the office For purposes of this retention requirement, a record is defined as: Any book, paper, map, photograph, or other information-recording device, regardless of physical form or characteristic, that is made, produced, executed, or received by any local government or officer thereof pursuant to law or in connection with the transaction of public business. Record as used herein shall not be deemed to include library materials, extra copies of documents created only for convenience of reference, and stocks of publications. See NYS Arts & Cultural Affairs Law 57.17(4) (emphasis added). The County Executives office, which had no role in development of the redistricting plan or the preparation of Local Law C, only would have possession of copies of documents, not the originals. As such, any missing file, such as copies of Local Law C and plaintiffs competing redistricting plan, were copies that were produced elsewhere. In addition, the County Executive has already provided copies of such 13

documents in discovery. Simply put, a party is not required to retain and produce multiple copies of the same document. Zubulake v. UBS Warburg, LLC, 220 F.R.D. 212, 218 (S.D.N.Y. 2003). In sum, plaintiffs reliance upon unsubstantiated accusations is an ill-advised insult against hard working County officials effort to provide documents, regardless of their relevance. Plaintiffs arguments are a frivolous attempt to deflect attention from material facts. Plaintiffs do not dispute that the County Executive held a public hearing before signing Local Law C. Moreover, plaintiffs do not dispute that they were allowed to depose the County Executive regarding his conducting of the public hearing and consideration of Local Law C. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 20. As such, even assuming the missing documents included information submitted to the County Executive, the fact remains that the County Executive considered this information before exercising his authority to sign the legislation despite opposition. POINT III DEFENDANTS ACTED IN GOOD FAITH Unable to show culpable conduct, plaintiffs nonetheless incredibly assert that defendants acted in bad faith or with gross negligence so that they are entitled to a presumption that the missing documents would be adverse to defendants. See Pl. Mem. at 17. Again, plaintiffs are wrong on the facts and law. Like before, plaintiffs argument is first premised on the Countys alleged failure to issue a written litigation hold. As demonstrated above, plaintiffs argument is a red 14

herring, given the Countys preservation and production of all documents relating to the 2011 redistricting process. But even if a written litigation hold were relevant, plaintiffs are wrong in its application. Not one Second Circuit case mentions the term litigation hold, let alone requires it to be written. Steuben Foods, Inc. v. Country Gourmet Foods, LLC, 2011 WL 1549450, 5 (W.D.N.Y. 2011) (holding that a written litigation hold is not a ground to presume or infer loss of relevant documents and holding that there is no Second Circuit case holding that a litigation hold must be in writing). Similarly, plaintiffs misapply this Courts holding in Essenter v. Cumberland Farms, Inc., 2011 WL 124505, 6-7 (N.D.N.Y., 2011), in which this Court found that spoliation of material evidence had occurred and held that gross negligence could be found for failing to take the steps to preserve the material evidence, including a litigation hold. Here, of course, there was no spoliation of material evidence. Moreover, as demonstrated above, this action was commenced within weeks of the enactment of Local Law C and soon thereafter, defendants provided plaintiffs with all documentation regarding the redistricting process. Similarly, plaintiffs revisit the actions of the County Executives Offices destruction of documents. Again, as detailed above, plaintiffs are unable to demonstrate that these actions were unlawful or that the documents were even relevant. Plaintiffs related attempt to characterize the new County Executive as having a cavalier attitude with regard to the County document retention policy is utterly specious. To the contrary, 15

the County Executive properly stated that he was familiar with the law and was abiding by it. Plaintiffs again resort to attacking Mr. Scarff for destroying his notes and Mr. Commisso for discarding copies of materials provided to all legislators. Plaintiffs mistakenly contend that they are entitled to an adverse presumption against the County because the discarding of these documents allegedly violated the Countys document retention policy. But even if theses sweeping allegations were true, the cases cited by plaintiffs support the conclusion that the actions under these circumstances would not trigger the presumption. See Latimore v. Citibank Fed. Sav. Bank, 151 F.3d 712, 716 (7th Cir. 1998)(the disappearance of Kernbauer's notes was inadvertent, and an inadvertent failure to comply with the regulation is not a violation of it. So the presumption did not attach); Favors v. Fisher, 13 F.3d 1235, 1239 (8th Cir. 1994) (citations omitted) (defendants testimony showed that he did not destroy the documents in anticipation of litigation). Once again, plaintiffs misleading assertions aside, defendants acted in good faith and plaintiffs are not entitled to any adverse inference. POINT IV PLAINTIFFS PROPOSED RELIEF IS UNJUSTIFIED Having failed to meet any of the requirements necessary to impose sanctions on defendants for alleged failure to produce material evidence, see Residential Funding Corp., 306 F.3d at 107, plaintiffs proposed relief is wholly inappropriate and patently unjustified. Under plaintiffs strained theory, even the innocent discarding of personal 16

reminder notes for preparing minutes, the recycling of extra copies of legislative handouts, and the supervised removal of duplicate copies and irrelevant confidential records would somehow warrant their unprecedented access to the Countys computer server and the deposition of the County Comptroller. This argument is flawed for a number of reasons. First, as exhaustively established above, plaintiffs cannot demonstrate any culpable conduct by defendants. Moreover, even with the expedited discovery schedule for the preliminary injunction hearing, defendants production of documents pertaining to the 2011 redistricting process was complete and thorough. Second, from the outset of this litigation, the County Department of Information Technology has assisted defendants counsel in the search for and production of relevant documents responsive to plaintiffs demands. See Diegel Aff. s 2-4. Nothing in the law or facts would justify plaintiffs intrusion into the Countys secured computer system. Third, most of the claimed missing documents (handwritten minute notes and legislative handouts) were hard copies that were never stored on the Countys computer system. Similarly, the County Executive does not even recall receiving any e-mails regarding the redistricting process. See Karlan Dec. Exh. 20 (Breslin Tr. 72) . As such, access to the Countys server to search for these documents is unwarranted. Fourth, the central issue in this action remains whether Local Law C of 2011 is lawful under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Plaintiffs scheme to gain access to sensitive material is indicative of its continued improper foray into irrelevant inquiries 17

and should not be endorsed by this Court. Simply stated, plaintiffs motion for discovery sanctions lacks both a factual foundation and legal basis. CONCLUSION For these reasons, defendants request an order denying plaintiffs motion for discovery sanctions in its entirety. Dated: June 12, 2012 Of Counsel: Catherine A. Barber, Esq. MURPHY, BURNS, BARBER & MURPHY, LLP By: Peter G. Barber, Esq. Attorneys for Defendant County of Albany 226 Great Oaks Boulevard Albany, New York, 12203 Telephone: 518-690-0096; Telefax: 518-690-0053 ALBANY COUNY ATTORNEY By: Thomas Marcelle, Esq. Attorneys for Defendant Board of Elections Department of Law 112 State Street, Suite 1010 Albany, New York, 12207 Telephone: 518-447-7110; Telefax: 518-447-5564

Of Counsel: Karry Culihan, Esq. Adam Giangreco, Esq.

18

Вам также может понравиться

- Rules of The Albany County Democratic CommitteeДокумент36 страницRules of The Albany County Democratic Committeetulocalpolitics100% (1)

- TU Center Naming Rights ContractДокумент29 страницTU Center Naming Rights ContracttulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- 2015 Albany Landfill Compliance Report PrintДокумент1 201 страница2015 Albany Landfill Compliance Report PrinttulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- Thruway Dec 1207Документ2 страницыThruway Dec 1207tulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- 2016 Albany County Budget AmendmentsДокумент2 страницы2016 Albany County Budget AmendmentstulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- Albany High School Vote BreakdownДокумент8 страницAlbany High School Vote BreakdowntulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- Board Minutes May 21 2015Документ1 страницаBoard Minutes May 21 2015tulocalpoliticsОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Transportation LawДокумент3 страницыTransportation LawFe EsperanzaОценок пока нет

- PEOPLE V GONZALES JRДокумент9 страницPEOPLE V GONZALES JRuranusneptune20Оценок пока нет

- LLB 5 YdcДокумент2 страницыLLB 5 Ydctasya lopaОценок пока нет

- Application For Work Permit FormДокумент6 страницApplication For Work Permit FormIsan Ismail100% (1)

- Heirs of Amparo Del Rosario vs. Santos 565 SCRA 1 (2008)Документ10 страницHeirs of Amparo Del Rosario vs. Santos 565 SCRA 1 (2008)Jessie Albert CatapangОценок пока нет

- Docket ReportДокумент5 страницDocket ReportWSETОценок пока нет

- Nego Case DoctrinesДокумент4 страницыNego Case DoctrinesFlorence RoseteОценок пока нет

- Nepali PoliticsДокумент19 страницNepali PoliticsSmaran PaudelОценок пока нет

- Occupiers Liability - Part 3 (OLA 1984)Документ50 страницOccupiers Liability - Part 3 (OLA 1984)李雅文Оценок пока нет

- Carriage of PassengersДокумент5 страницCarriage of PassengersLoueljie AntiguaОценок пока нет

- 482 (HC) MaharudrappaДокумент7 страниц482 (HC) Maharudrappaadv_vinayakОценок пока нет

- Model Law PDFДокумент8 страницModel Law PDFRap PatajoОценок пока нет

- Managerial Remuneration Checklist FinalДокумент4 страницыManagerial Remuneration Checklist FinaldhuvadpratikОценок пока нет

- Nevada DETR Response To PUA LawsuitДокумент27 страницNevada DETR Response To PUA LawsuitMichelle Rindels67% (3)

- Labor Cases 2 (OFWs)Документ24 страницыLabor Cases 2 (OFWs)Jeremy LlandaОценок пока нет

- 100 Manuel Labor Notes PDFДокумент20 страниц100 Manuel Labor Notes PDFTopnotch2015Оценок пока нет

- UCEDA Admissions Application 2021Документ5 страницUCEDA Admissions Application 2021Adriana OsorioОценок пока нет

- Lawyers Duties in Handling Clients Case CompleteДокумент23 страницыLawyers Duties in Handling Clients Case CompleteAnne Lorraine DioknoОценок пока нет

- Character Statutory DeclarationДокумент4 страницыCharacter Statutory DeclarationErin GamerОценок пока нет

- Divorce Position Paper by EdДокумент5 страницDivorce Position Paper by EdAnonymous TLYZbXqxWzОценок пока нет

- Letter To Town of Highlands Re Short Term Rental Regulations 2022.08.10Документ46 страницLetter To Town of Highlands Re Short Term Rental Regulations 2022.08.10Michael JamesОценок пока нет

- BSNL JudgementДокумент15 страницBSNL JudgementJasvinder SinghОценок пока нет

- NEA V COAДокумент3 страницыNEA V COAthethebigblackbook100% (1)

- Micro Insurance Product: Tata AIA Life Insurance Saat SaathДокумент5 страницMicro Insurance Product: Tata AIA Life Insurance Saat SaathSample accountОценок пока нет

- G.R. No. L-22948Документ4 страницыG.R. No. L-22948Karen Gina DupraОценок пока нет

- General Power of AttorneyДокумент2 страницыGeneral Power of AttorneyValix CPAОценок пока нет

- Departmental Examination of Acs OfficersДокумент4 страницыDepartmental Examination of Acs OfficersSatrajit NeogОценок пока нет

- Litigation Annexure - SWAMIH - Template - 210323Документ372 страницыLitigation Annexure - SWAMIH - Template - 210323shruti goyalОценок пока нет

- PLM Juris Doctor CurriculumДокумент2 страницыPLM Juris Doctor Curriculumglee0% (1)

- The 2012 Philip C. Jessup Internaional Law Moot Court CompetitionДокумент48 страницThe 2012 Philip C. Jessup Internaional Law Moot Court Competitionprakash nanjanОценок пока нет