Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

SC

Загружено:

Ila Daril FadhilahИсходное описание:

Авторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

SC

Загружено:

Ila Daril FadhilahАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227 Published online 18 February 2003 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.

56

First-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar

D. JURKOVIC, K. HILLABY, B. WOELFER, A. LAWRENCE, R. SALIM and C. J. ELSON

Early Pregnancy and Gynaecology Assessment Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Kings College Hospital, London, UK

K E Y W O R D S: Cesarean section scar; ectopic pregnancy; rst trimester; ultrasound

ABSTRACT

Objective To describe rst-trimester ultrasound diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into uterine Cesarean section scars. Methods All women referred for an ultrasound scan because of suspected early pregnancy complications were screened for pregnancies implanted into a previous Cesarean section scar. The management of Cesarean section scar pregnancies included transvaginal surgical evacuation, medical treatment with local injection of 25 mg methotrexate into the exocelomic cavity and expectant management. Results Eighteen Cesarean section scar pregnancies were diagnosed in a 4-year period. The prevalence in the local population was 1 : 1800 pregnancies. Surgical treatment was used in eight women and it was successful in all cases. The respective success rates of medical treatment and expectant management were 5/7 (71%) and 1/3 (33%). Five women (28%) required blood transfusion and one woman (6%) had a hysterectomy. Conclusions Cesarean section scar pregnancies are more common than previously thought. When the diagnosis is made in the rst trimester the prognosis is good and the risk of hysterectomy is relatively low. Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

INTRODUCTION

Implantation of the placenta into the uterine scar following a previous Cesarean section is associated with severe late pregnancy complications such as placenta previa and placenta accreta1 . In women with a history of multiple Cesarean sections the incidence of placenta previa is ten times higher compared with women who had

vaginal deliveries2 . When the placenta is implanted over the uterine scar, it is abnormally adherent in 3040% of cases, which often causes uncontrollable hemorrhaging at delivery2,3 . Abnormally inserted placentae are responsible for 5065% of all obstetric hysterectomies, 66% of which have a history of previous Cesarean sections4,5 . The clinical signicance of this complication is emphasized by the Condential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths, which showed that 72% of all maternal deaths associated with placenta previa in the UK between 1991 and 1999 occurred in women who had at least one previous Cesarean section6 . Placenta accreta can be diagnosed by ultrasound in the third trimester of pregnancy. The diagnostic criteria include an absent decidual interface between the placenta and myometrium as well as unusual dilatation of the vessels under the placental implantation site7 . Although the reported accuracy of ultrasound diagnosis in the third trimester is high8 , the late detection of placenta accreta is of limited value, as it does not help to prevent serious maternal morbidity associated with this condition. There are only a handful of reports describing the rst-trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into Cesarean section scars9 22 (Table 1). In this report we describe 18 cases of pregnancies implanted into the previous lower segment Cesarean section scar, which were diagnosed in our unit over a 4-year period. All were detected in the rst trimester and we discuss the controversies surrounding both the diagnosis and clinical management of this condition.

METHODS

This study was set in a dedicated tertiary referral early pregnancy assessment ultrasound unit in an inner city

Correspondence to: Mr D. Jurkovic, Early Pregnancy and Gynaecology Assessment Unit, 6th Floor, Ruskin Wing, Kings College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 8RX, UK (e-mail: davor.jurkovic@kcl.ac.uk) Accepted: 5 December 2002

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

ORIGINAL PAPER

Cesarean scar pregnancies

Table 1 Treatment of Cesarean scar pregnancy: summary of the literature Gravidity & Previous hCG Decient Parity LSCS (n) (IU/L) Viability myometrium N/K G2 P1 G2 P1 N/K 1 1 N/K N/K 5789 N/K Yes Yes No No No

221

Ref. 9 10 11

Treatment Laparotomy, hysterotomy and curretage Expectant Local MTX

Success Yes No No N/K

Outcome

12

G3 P2

62 000

Yes

Yes

Expectant

No

13

G4 P2

12 000

Yes

Yes

Systemic MTX

Yes

14 15 16 17

G4 P1 G4 P2 G8 P5 G3 P2

1 2 1 1

54 24 940 7250 21 866

No N/K No Yes

Yes Yes Yes Yes

Laparoscopic surgery Laparotomy Local glucose, systemic MTX Laparotomy, hysterotomy, uterine artery ligation, systemic MTX Local MTX Laparotomy US-guided aspiration Laparotomy Systemic MTX

Yes Yes Yes Yes

Emergency LSCS hysterectomy at 35 weeks Laparotomy; pregnant 4 months later normal intrauterine pregnancy Given local MTX and KCl; 3 months to ultrasound resolution Resolution of hCG in 3 months; pregnant 8 months later normal intrauterine pregnancy Follow-up visit after 1 year all well Pregnant 6 months later normal twin intrauterine pregnancy 8 weeks to resolution Follow-up visit after 4 months all well Resolution of hCG in 2 months Pregnant 2 months later normal intrauterine pregnancy Given systemic MTX resolution of hCG in 3 weeks N/K N/K

18 19 20 21 22

G6 P1 G3 P2 G2 P1 G3 P2 G5 P4

1 2 1 2 4

23 328 N/K 69 000 19 755 11 306

Yes No No Yes Yes

Yes Yes Yes Yes No

Yes Yes No Yes Yes

Ref., reference; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; G, gravida; P, para; N/K, not known; MTX, methotrexate; US, ultrasound; LSCS, lower segment Cesarean sections; KCl, potassium chloride.

hospital. The unit serves a racially mixed population with a high level of socioeconomic deprivation. Women with suspected early pregnancy complications were either self-referred for assessment or they were referred to the unit by a local general practitioner, the hospital accident and emergency department or one of the hospital consultants. Tertiary referrals of women with ectopic pregnancies were also received from other hospitals within the UK. All women attending the early pregnancy unit had a positive urine pregnancy test, which is routinely performed prior to clinical and ultrasound assessment TM (Clearview HCG II , Unipath, Bedford, UK). The test is a monoclonal-based antibody test, which, according to the manufacturers specications, has a sensitivity of 99% at a urine -human chorionic gonadotropin (-hCG) level greater than 25 IU/L. All women were assessed by gynecologists who were fully trained in transvaginal sonography. A full history was always taken initially and entered into a clinical database (PIA Fetal Database, Version 3.23, Viewpoint Bildverarbeitung GmbH, Munich, Germany). When appropriate, clinical examination was also carried out by the attending physician, including a vaginal speculum examination. A transvaginal ultrasound scan was then performed to examine the viability and location of the pregnancy.

Figure 1 Four-week gestational sac implanted into the lower segment Cesarean section scar.

Implantation into the previous Cesarean section scar (Figure 1) was diagnosed when the following criteria were satised: (1) empty uterine cavity; (2) gestational sac located anteriorly at the level of the internal os

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

222

Jurkovic et al.

covering the visible or presumed site of the previous lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar; (3) evidence of functional trophoblastic/placental circulation on Doppler examination, which was dened by the presence of an area of increased peritrophoblastic or periplacental vascularity on color Doppler examination, and high-velocity (peak velocity > 20 cm/s), low-impedance (pulsatility index < 1) ow velocity waveforms on pulsed Doppler examination23 ; (4) negative sliding organs sign, which was dened as the inability to displace the gestational sac from its position at the level of the internal os using gentle pressure applied by the transvaginal probe. In all women with the diagnosis of pregnancy implanted into the lower segment Cesarean section scar the appearance of the myometrium at the implantation site was also examined. The scar was described as decient whenever there was a visible gap in the myometrium of the anterior uterine wall and the pregnancy was seen bulging towards the urinary bladder (Figures 2 and 3). A blood sample was obtained from each woman to ascertain the full blood count, blood group, crossmatch and serum -hCG (World Health Organization, Third International Reference 75/537). In women who were considered suitable for medical treatment with methotrexate, baseline liver and renal function tests were also performed. Women were informed about the poor understanding of the natural history and clinical signicance of rsttrimester pregnancies implanted into previous Cesarean section scars. Clinical symptoms, pregnancy viability, gestational age and evidence of myometrial deciency determined the management in each individual case. Women with minimal clinical symptoms who had small non-viable pregnancies were considered suitable for all management options including expectant management. Women with a viable pregnancy > 7 weeks gestation and those with signs of abnormal placentation involving the myometrium were offered medical treatment with

Figure 3 Transverse section of the uterus at 6 weeks gestation showing a gestational sac with a live embryo protruding through the left side of the Cesarean section scar.

Figure 2 Longitudinal section of the uterus showing a 7-week gestational sac implanted into a previous Cesarean section scar and protruding towards the urinary bladder.

local injection of methotrexate. Surgical evacuation of pregnancy was offered to all women with a pregnancy < 7 weeks, those who experienced heavy bleeding and those in whom non-surgical treatment failed. However, the management plan was sometimes modied depending on the womans own views and preferences and in some cases on the opinion of the referring consultant obstetricians and gynecologists. Medical treatment involved an injection of 25 mg methotrexate directly into the pregnancy. The injection was administered transvaginally under continuous ultrasound guidance using a 20-G needle. Antibiotic prophylaxis of a single intravenous dose of 1.5 g cefuroxime and 500 mg metronidazole was given to all women. All procedures were performed on an outpatient basis under mild analgesia (50 mg pethidine and 10 mg metoclopramide intravenously). In cases with detectable embryonic cardiac activity, embryocide was performed rst by the intracardiac injection of 0.10.2 nmol potassium chloride (KCl). Surgery involved the use of suction curettage under ultrasound guidance. In cases complicated by heavy intraoperative bleeding, a 1622-G Foley catheter was inserted at the level of the implantation site and inated with 3090 mL saline in an attempt to achieve hemostasis by compression. The catheter was left in situ for 1224 h and then gradually deated and removed. Follow-up consisted of weekly outpatient clinical assessment and measurements of serum hCG levels. Once hCG levels declined to < 25 IU/L an ultrasound examination was performed to assess the size of the retained products of conception. Ultrasound examinations were then arranged on a monthly basis until it was conrmed that all pregnancy tissue had been spontaneously expelled or absorbed. All women who were planning future pregnancies were encouraged to attend for an early scan in order to assess the location of pregnancy.

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

Cesarean scar pregnancies

223

RESULTS

Over the 4-year period 18 245 women with suspected early pregnancy complications attended the early pregnancy unit. Eighteen women were found to have pregnancies implanted into a previous lower segment Cesarean section scar. Eight of these women were referred from other hospitals, and ten lived locally. As only 12% of women with early pregnancy problems were referred from other units, the prevalence of Cesarean scar pregnancy in the local population of women attending the early pregnancy assessment unit was approximately 1 : 1800. The mean number of previous Cesarean sections in women with scar pregnancies was 1.9 (range, 14) and 13/18 (72%) of these women had undergone previous multiple Cesarean sections (Table 2). The gestational age of the Cesarean scar pregnancies ranged between 4 and 23 weeks. On ultrasound examination, 11/18 (61%) pregnancies had evidence of cardiac activity. However, all pregnancies diagnosed at > 12 weeks gestation consisted only of retained placental tissue following rst-trimester embryonic demise. Eight (44%) women with Cesarean scar pregnancies were initially treated surgically, seven medically (39%), and three expectantly (17%). Surgical management was successful in all cases, although three of eight (38%) women suffered signicant bleeding (5001000 mL) which required the insertion of a Foley catheter into the cervix in order to achieve hemostasis. There were no cases of retained products of conception following surgical treatment. In the group of women who were managed medically the success rate was 5/7 (71%). Two women in this group required surgical intervention and blood transfusion due to heavy vaginal bleeding (> 1000 mL). A woman with heterotopic intrauterine and Cesarean scar pregnancies was treated only with local injection of KCl into the scar pregnancy. The intrauterine pregnancy remained viable and progressed normally until the third trimester. At 31 weeks she suffered a major antepartum hemorrhage and an emergency Cesarean section was performed. At the operation the uterine scar appeared thin and severely decient. Bleeding was originating from the left lateral edge of the scar where a small amount of retained trophoblast tissue was found. Histological examination conrmed the presence of rst-trimester trophoblast. However, due to the special circumstances of this case the management was classied as successful. In women successfully treated with methotrexate the hCG resolution time was between 6 and 10 weeks. None of the women in this subgroup experienced any side effects, which could be attributable to the medication. Expectant management was successful in one of three cases (33%). This woman had an incomplete miscarriage at 10 weeks. Another women, who was diagnosed with a scar pregnancy at 5 weeks gestation, had a follow-up scan in another hospital which showed that embryonic demise occurred at 10 weeks. She was given systemic methotrexate and the pregnancy resolved without need for further intervention. The third woman who was managed

expectantly had a spontaneous miscarriage at 17 weeks gestation. She suffered a severe hemorrhage requiring an emergency hysterectomy. At the time of writing, seven of the women with previous Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancies had tried for another pregnancy. Five of them (71%) have been successful, all achieving normal singleton intrauterine pregnancies.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of rst-trimester Cesarean scar pregnancies was much higher in the population of women attending our early pregnancy unit than would be expected from the review of individual case reports from the literature. This may be explained by the liberal use of transvaginal sonography in our unit, which facilitates the diagnosis of abnormal uterine implantation. In addition, the appearance of a previous Cesarean section scar is routinely examined in our unit in both pregnant and non-pregnant women. An effort to exclude implantation into the uterine scar is always made in all women with a history of previous Cesarean section attending for an early pregnancy scan. Previous studies have shown that women with a history of Cesarean section are more likely to experience miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, abruptio placentae, placenta previa and placenta accreta24 . Some of these complications, such as tubal ectopic pregnancy, are likely to be a result of postoperative infection and adhesions, which may occur after any abdominal surgery. Our study showed that 44% of Cesarean scar pregnancies ended in spontaneous rst-trimester miscarriage. This rate would probably be higher if all the women with a viable pregnancy on the initial scan were managed expectantly. However, the mean maternal age was 36 years in this study, which may also have been a signicant contributing factor to this high miscarriage rate. We have already referred to the high prevalence of placenta previa and accreta in women with multiple Cesarean sections1 5 . In 10 of 14 cases (71%) of rst-trimester Cesarean scar pregnancies reported in the literature, the authors observed that the pregnancy penetrated deep into the myometrium (Table 1). Typically, the anterior uterine wall appeared thin in these cases and the pregnancy was seen bulging through the anterior uterine wall, reaching to within a few millimeters from the bladder. We saw similar ndings in 11/18 (61%) women in our study (Figures 2 and 3). Most previous reports classied these cases as intramural pregnancies. However, the term intramural pregnancy implies that the pregnancy is completely conned to the myometrium, which is not the case with the majority of scar pregnancies. As the rst-trimester ndings closely resemble the appearance of placenta and myometrium in cases of placenta accreta later in pregnancy, the term abnormally adherent trophoblast/placenta, may be more appropriate. The propensity of the Cesarean scar pregnancy to invade deep into the myometrium could be explained

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

224

Table 2 Characteristics of 18 women with rst-trimester Cesarean scar pregnancies

Maternal Case age no. (years) Viability Non-viable N/A Yes D&C, Foley catheter D&C D&C Yes Yes Yes CRL (mm) Management Success Complications 1 11 7620 14

Conception

Initial Gestational hCG sac diameter Gravidity Previous Gestation level (mm) & Parity LSCS (n) (weeks) (IU/L) Decient myometrium N/A

Time to resolution (weeks)

Future pregnancy Not trying

39

Spontaneous

G3, P1

2 1 6 4622 9 Non-viable N/A No

33

Spontaneous

G2,P1

9730

11

Non-viable

N/A

No

Intraoperative hemorrhage < 1000 mL None None

N/A N/A

42

Spontaneous

G6,P1

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 2 10 N/K 34 Non-viable N/A Yes D&C Yes None N/A 2 23 283 25 Non-viable N/A Yes D&C, Foley catheter D&C D&C D&C, Foley catheter Yes 10.8 Yes Yes N/A Not yet conceived Normal pregnancy 5 months later Normal pregnancy 9 months later Not trying 2 4 2 6 14 11 184 N/K 10 25 Viable Non-viable 3 N/A Yes No 6 N/K 20 Viable 2.4 No Yes Yes Yes Intraoperative hemorrhage < 1000 mL None N/A 10 N/A Not yet conceived Not trying Not trying 1 2 8 18 090 16 Viable 6 23 700 19 Viable 18.7 Yes No None Intraoperative hemorrhage < 1000 mL None Local methotrexate Local methotrexate Hemorrhage > 1000 mL, D&C, blood transfusion 6 N/A Not trying Not trying (continued overleaf )

27

Spontaneous

G4,P2

37

Spontaneous

G5,P2

34

Spontaneous

G4,P2

7 8

35 30

Spontaneous Spontaneous

G6,P5 G3,P2

Spontaneous

G4,P3

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

10

38

Spontaneous

G7,P2

Jurkovic et al.

Table 2 (Continued)

Cesarean scar pregnancies

Maternal Case age no. (years) Viability Viable 2.3 Yes Local methotrexate Yes No None Yes None 6 CRL (mm) Management Success Complications 1 6 15 540 7

Conception

Initial Gestational hCG sac diameter Gravidity Previous Gestation level (mm) & Parity LSCS (n) (weeks) (IU/L) Decient myometrium Time to resolution (weeks)

Future pregnancy

11

34

Spontaneous

G4,P2

12 2 6 64 299 25 Viable 2.3 Yes

39

Spontaneous

G5,P2

3823

Viable

N/A

Yes

10 N/A

Normal pregnancy 6 months later Not trying Not trying

13

43

spontaneous

G7,P2

Local methotrexate Local methotrexate

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 3 9 92 880 37 Viable 23.8 Yes Yes Hemorrhage > 1000 mL, embolization D&C, blood transfusion None N/K Awaiting IVF 3 7 68 800 27 Viable 16 Yes Local methotrexate + KCl Local KCL Yes N/A Not trying 3 5 3013 7 Non-viable N/A No Expectant No N/K Normal pregnancy 6 months later 2 9 13.5 8 Viable 1.6 No Expectant for 4 months 2.3 N/K Expectant Yes 16 Normal pregnancy 3 months later No N/A 2 6 N/K 12 Viable Hemorrhage at 31 weeks > 1000 mL Emergency LSCS Missed miscarriage at 10 weeks Systemic methotrexate Prolonged bleeding < 1000 mL Severe hemorrhage at 17 weeks > 1000mL Hysterectomy

14

43

IVF

G5,P3

15

36

Spontaneous (heterotopic)

G10,P3

16

35

Spontaneous

G8,P3

17

35

Spontaneous

G5,P2

18

38

IVF

G3,P2

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; CRL, crownrump length; IVF, in-vitro fertilization; N/K, not known; N/A, not applicable; D&C, dilatation and curettage; KCl, potassium chloride; LSCS, lower segment Cesarean sections.

225

226

Jurkovic et al. pregnancy and low intrauterine pregnancy becomes more difcult. Vial et al.19 proposed a list of sonographic criteria which should be present in order to make the diagnosis of a Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy. They included: (i) the trophoblast must be mainly located between the bladder and the anterior uterine wall; (ii) no fetal parts must be visible in the uterine cavity; (iii) on a sagittal view of the uterus running through the amniotic sac, a discontinuity in the anterior wall of the uterus should be identied. However, in order to avoid false-positive diagnosis of scar implantation in cases of incomplete miscarriages being expelled from the uterine cavity, we feel that in women with non-viable pregnancies, Doppler ultrasound and sliding organs sign should be used to conrm the diagnosis of a scar pregnancy. In cases of miscarriages of intrauterine pregnancies the gestational sac appears avascular, reecting the fact that the sac has become detached from its implantation site, whereas in Cesarean section scar pregnancies the gestational sac appears well-perfused on Doppler examination. With limited experience of Cesarean scar pregnancies in the rst trimester, it is difcult to decide on optimal management in individual cases. The majority of women in previous reports were treated either surgically or medically, whilst two women were managed expectantly. It is interesting that the authors of the previous case reports who chose surgical treatment all opted for the transabdominal approach, using either laparoscopy or open laparotomy to excise the pregnancy from the Cesarean section scar. Although the treatment was successful in all cases, we achieved a similar success rate using a transcervical approach, which is simpler and has a quick postoperative recovery. Analysis of published case reports showed that the success of methotrexate, when used as the initial treatment option, was 80%. One woman in whom treatment failed had an open laparotomy and excision of pregnancy. These results are similar to the 71% success rate of medical treatment in our study. There are two reports of expectant management in the literature. One of these women required additional treatment with methotrexate12 , whilst the other had an emergency Cesarean hysterectomy at 35 weeks gestation10 . Expectant management failed in two of three cases in our study, one women requiring methotrexate and the other an emergency hysterectomy. These results indicate that expectant management of viable scar pregnancies carries a signicant risk of emergency hysterectomy if the pregnancy progresses beyond the rst trimester.

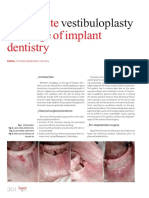

Figure 4 Longitudinal section of a non-pregnant uterus showing a well-healed lower segment Cesarean section scar.

Figure 5 Longitudinal section of a retroverted non-pregnant uterus showing a highly decient lower segment Cesarean section scar.

by the characteristics of uterine Cesarean scars in nonpregnant women25 . The majority of scars are well-healed (Figure 4), but in a small number of women the anterior uterine wall is decient (Figure 5). These decient scars are more likely to occur after multiple Cesarean sections due to brosis, which leads to poor vascularity of the lower uterine segment and impaired postoperative healing. The scar surface area is increased in women with multiple sections, which in turn increases the chance of a pregnancy implanting into the scar. This may explain both the high number of previous multiple Cesarean sections and the high proportion of abnormally inserted placentae in cases of scar implantation. There is no agreement on the best method and criteria to diagnose Cesarean scar pregnancies. However, transvaginal ultrasound has been used in most studies and is likely to emerge as a future gold standard for the diagnosis of scar implantation. Diagnosis is relatively simple early in pregnancy, but as the pregnancy progresses, the distinction between Cesarean scar, cervical

CONCLUSIONS

The prognosis of a Cesarean section scar pregnancy diagnosed in the rst trimester appears to be much better than the prognosis of placenta previa/accreta detected in the third trimester. However, given the uncertainties about the diagnostic criteria and prognosis,

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

Cesarean scar pregnancies the main question is whether any form of treatment is justied in these cases. We feel that an experienced operator using transvaginal sonography should be able to establish with a high degree of accuracy the diagnosis of scar pregnancy and detect an abnormal adherence of trophoblast to the myometrium. Current data also indicate that expectant management is rarely successful and is particularly unsuitable for women with viable scar pregnancies. It is also important to emphasize that the maternal morbidity and length of follow-up both increase with gestation. Myometrial involvement is a particularly unfavorable feature, which makes surgical termination of pregnancy very difcult. In addition, it is very likely, although unproven, that these women will develop placenta previa/accreta should the pregnancy be allowed to progress into the third trimester. In the absence of reliable scientic data we believe that each woman should be presented with all available information and given the opportunity to decide on the management of her pregnancy. Should she opt for treatment, a local injection of methotrexate and transcervical aspiration of pregnancy should be used in preference to a laparoscopy or laparotomy.

227

9. Rempen A, Albert P. Diagnosis and therapy of early pregnancy implanted in the scar of caesarean section. Z Geburtsh u Perinat 1990; 194: 4648. 10. Herman A, Weinraub Z, Avrech O, Maymon R, Ron-El R, Bukovsky Y. Follow up and outcome of isthmic pregnancy located in a previous caesarean section scar. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995; 102: 839841. 11. Lai YM, Lee JD, Lee CL, Chen TC, Soong YK. An ectopic pregnancy embedded in the myometrium of a previous cesarean section scar. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995; 74: 573576. 12. Godin PA, Bassil S, Donnez J. An ectopic pregnancy developing in a previous caesarean section scar. Fertil Steril 1997; 67: 398400. 13. Ravhon A, Ben-Chetrit A, Rabinowitz R, Neuman M, Beller U. Successful methotrexate treatment of a viable pregnancy within a thin uterine scar. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1997; 104: 628629. 14. Lee CL, Wang CJ, Chao A, Yen CF, Soong YK. Laparoscopic management of an ectopic pregnancy in a previous Caesarean section scar. Hum Reprod 1999; 14: 12341236. 15. Neiger R, Weldon K, Means N. Intramural pregnancy in a cesarean section scar. J Reprod Med 1998; 43: 9991001. 16. Roberts H, Kohlenber C, Lanzarone V, Murray H. Ectopic pregnancy in lower segment uterine scar. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynecol 1998; 38: 114116. 17. Valley MT, Pierce JG, Daniel TB, Kaunitz AM. Cesarean scar pregnancy: Imaging and treatment with conservative surgery. Obstet Gynecol 1998; 91: 838840. 18. Seow KM, Cheng WC, Chuang J, Lee C, Tsai YL, Hwang JL. Methotrexate for cesarean scar pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. J Reprod Med 2000; 45: 754757. 19. Vial Y, Petignat P, Hohlfeld P. Pregnancy in a caesarean scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2000; 16: 592593. 20. Ayoubi J-M, Fanchin R, Meddoun M, Fernandez H, Pons JC. Conservative treatment of complicated cesarean scar pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2001; 80: 469470. 21. Seow KM, Hwang JL, Tsai YL. Ultrasound diagnosis of a pregnancy in a Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001; 18: 547549. 22. Shufaro Y, Nadjari M. Implantation of a gestational sac in a cesarean section scar. Fertil Steril 2001; 75: 1217. 23. Jurkovic D, Jauniaux E, Kurjak A, Hustin J, Campbell S, Nicolaides KH. Transvaginal color Doppler assessment of uteroplacental circulation in early pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1991; 77: 365369. 24. Hemminki E, Merilainen J. Long term effects of cesarean sections: Ectopic pregnancies and placental problems. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 15691574. 25. Jarvela IY, Slakevicius P, Kelly S, Ojha K, Campbell S, Nargund G. Cesarean delivery scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2002; 19: 632633.

REFERENCES

1. Clark S, Koonings PP, Phelan JP. Placenta previa-accreta and prior cesarean section. Obstet Gynecol 1985; 66: 8992. 2. Miller DA, Chollet JA, Goodwin TM. Clinical risk factors for placenta praevia-placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997; 177: 210214. 3. Zaideh SM, Abu-Heija AT, El-Jallad MF. Placenta praevia and accreta: analysis of a two-year experience. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1998; 46: 9698. 4. Zelop CM, Harlow BL, Frigoletto FD, Safon LE, Saltzman DH. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993; 168: 14431448. 5. Castaneda S, Karrison T, Ciblis LA. Peripartum hysterectomy. J Perinal Med 2000; 28: 472481. 6. Why Mothers Die. Reports on Condential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 19911999, HSMO: London, 1996, 1998, 2001. 7. Jauniaux E, Toplis PJ, Nicolaides KH. Sonographic diagnosis of a non-previa placenta accreta. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1996; 7: 5860. 8. Lerner JP, Deane S, Timor-Tritsch IE. Characterization of placenta accreta using transvaginal sonography and color Doppler imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1995; 5: 198201.

Copyright 2003 ISUOG. Published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2003; 21: 220227.

Вам также может понравиться

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeОт EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (5794)

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)От EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Рейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (98)

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceОт EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (895)

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersОт EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (344)

- PLKFJDHKDFNBVДокумент1 страницаPLKFJDHKDFNBVIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingОт EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (399)

- AsdfghjklДокумент1 страницаAsdfghjklIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- MnjklhgbfjkbkiyvДокумент1 страницаMnjklhgbfjkbkiyvIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerОт EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (271)

- LPK ,,JKGBHGCFMNДокумент1 страницаLPK ,,JKGBHGCFMNIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaОт EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (266)

- AsdfghjkloДокумент1 страницаAsdfghjkloIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItОт EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (838)

- AbcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzДокумент1 страницаAbcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyzIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryОт EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (231)

- Purpura Henoch Schonlein 1Документ9 страницPurpura Henoch Schonlein 1Aninditya Christa MaharaniОценок пока нет

- DiatomsДокумент3 страницыDiatomsIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Kuliah PendahuluanДокумент10 страницKuliah PendahuluanIla Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureОт EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (474)

- What Is Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) ?Документ4 страницыWhat Is Henoch-Schönlein Purpura (HSP) ?Ila Daril FadhilahОценок пока нет

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnОт EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnРейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (234)

- Curriculum Vitae: Allah Bakhsh KhosoДокумент2 страницыCurriculum Vitae: Allah Bakhsh KhosoKhoso BalochОценок пока нет

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyОт EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyРейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (2259)

- Apacible NCM119-LP1 LeadershipДокумент15 страницApacible NCM119-LP1 LeadershipUlah Vanessa BasaОценок пока нет

- Work Immersion Parent Consent FormДокумент2 страницыWork Immersion Parent Consent FormJohnArgielLaurenteVictor88% (8)

- Qlaira Film-Coated Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - (Emc)Документ1 страницаQlaira Film-Coated Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SMPC) - (Emc)Rand KamalОценок пока нет

- Dwnload Full Foundations of Maternal Newborn and Womens Health Nursing 7th Edition Murray Test Bank PDFДокумент35 страницDwnload Full Foundations of Maternal Newborn and Womens Health Nursing 7th Edition Murray Test Bank PDFroxaneblyefx100% (13)

- Materi PustakaДокумент22 страницыMateri Pustakaayuslst30Оценок пока нет

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaОт EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (45)

- 2022 FWN Magazine - Most Influential Filipina Women in The World Commemorative IssueДокумент52 страницы2022 FWN Magazine - Most Influential Filipina Women in The World Commemorative IssueFilipina Women's NetworkОценок пока нет

- HLFPPT CSR Competency Statement PDFДокумент9 страницHLFPPT CSR Competency Statement PDFShivi RawatОценок пока нет

- Chung 2016 Stop Bang QuestionnaireДокумент8 страницChung 2016 Stop Bang QuestionnaireDicka adhitya kamilОценок пока нет

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreОт EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (1090)

- Dr. Michael Banks License RevocationДокумент69 страницDr. Michael Banks License RevocationWKYC.comОценок пока нет

- Mdindia Healthcare Services (Tpa) Pvt. LTD.: Claim FormДокумент4 страницыMdindia Healthcare Services (Tpa) Pvt. LTD.: Claim FormShubakar ReddyОценок пока нет

- Narrative Report BLSДокумент6 страницNarrative Report BLSSoriano Armenio67% (3)

- Ensuring A Patient's Right To Pastoral Care and Spiritual ServicesДокумент6 страницEnsuring A Patient's Right To Pastoral Care and Spiritual ServicesArwenn BeragoОценок пока нет

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)От EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Рейтинг: 4.5 из 5 звезд4.5/5 (121)

- Aesthetic Medicine Training CourseДокумент8 страницAesthetic Medicine Training Coursedrdahabra3Оценок пока нет

- AOP-2024-narrative FINALДокумент66 страницAOP-2024-narrative FINALjasper manuelОценок пока нет

- Prof. Herkutanto - Informed Consent Sebagai Pencegahan Tuntutan 2017Документ33 страницыProf. Herkutanto - Informed Consent Sebagai Pencegahan Tuntutan 2017muslih setia ardi cahyanaОценок пока нет

- Neuro Lymphatic MassageДокумент2 страницыNeuro Lymphatic Massagewolfgangl70Оценок пока нет

- Aspects of Early Movement Therapy in Line With The Medical DiagnosisДокумент2 страницыAspects of Early Movement Therapy in Line With The Medical DiagnosisHajduGrétaОценок пока нет

- Revchilanestv 5103061042Документ10 страницRevchilanestv 5103061042María Augusta Robayo UvilluzОценок пока нет

- BookletДокумент80 страницBookletHarjot SinghОценок пока нет

- 4-Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) As A Practice For Supporting Chronic Disease Healthcare A Practitioners' PerspectiveДокумент10 страниц4-Emotional Freedom Techniques (EFT) As A Practice For Supporting Chronic Disease Healthcare A Practitioners' PerspectiveFria ZafriaОценок пока нет

- Up-To-Date at The Age of Implant Dentistry: VestibuloplastyДокумент3 страницыUp-To-Date at The Age of Implant Dentistry: VestibuloplastyDemmy WijayaОценок пока нет

- LabservicesДокумент91 страницаLabservicesendale gebregzabherОценок пока нет

- Wandilla Qatar PresentationДокумент31 страницаWandilla Qatar PresentationAnthonyОценок пока нет

- Summary For The Case Study On MastectomyДокумент2 страницыSummary For The Case Study On MastectomyNishi SharmaОценок пока нет

- Ayobunmi Pacheco - Assistant: Apacheco@veg - VetДокумент17 страницAyobunmi Pacheco - Assistant: Apacheco@veg - Vetapi-207993624Оценок пока нет

- PSmarkup - ARTIKEL PRENATAL MASSAGE-LILIS SURYA WATIДокумент9 страницPSmarkup - ARTIKEL PRENATAL MASSAGE-LILIS SURYA WATIRiya WahyuniОценок пока нет

- Primary Health CentreДокумент22 страницыPrimary Health CentreRakersh Patidar100% (1)

- Treatment and OutcomeДокумент26 страницTreatment and OutcomeChristine EnriquezОценок пока нет

- Academic Calender2023Документ37 страницAcademic Calender2023VUDIKALA BHARATH KUMARОценок пока нет

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossОт EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossРейтинг: 4 из 5 звезд4/5 (6)