Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Risk Management Presentation April 22 2013

Автор:

George LekatisАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Risk Management Presentation April 22 2013

Автор:

George LekatisАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Page |1

International Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (IARCP)

1200 G Street NW Suite 800 Washington, DC 20005-6705 USA Tel: 202-449-9750 www.risk-compliance-association.com

Top 10 risk and compliance management related news stories and world events that (for better or for worse) shaped the week's agenda, and what is next

Dear Member, I really enjoyed this paper from the Financial Conduct Authority in UK with title:

Applying behavioural economics at the Financial Conduct Authority

WOW! Now I know what was missing from the old FSA! They deserved to die. I love behavioural economics. This is one of the few areas we can explain that everybody (outside the financial services industry of course) is too stupid or has lost his mind, so it is not likely to understand what we do.

My summary of the paper: A fool and his money are soon parted.

It is science, of course. And, it is a really excellent paper, and you should study it. I t could become the manual for every expert witness in the financial services. All the good excuses are there. It this paper, one of the questions is: Why consumer choice in retail financial products and services is particularly prone to errors?

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |2

Some answers:

1.Many products are inherently complex for most people. {My understanding: Most people are too small, too poor, too stupid} To add insult to the injury the paper continues: Faced with complexity, consumers can simplify decisions in ways that lead to errors, such as focusing only on headline rates

2.Decisions may require assessing risk and uncertainty. People are generally bad (even terrible) intuitive statisticians and are prone to making systematic errors in decisions involving uncertainty.

{My understanding: People are generally bad (even terrible) statisticians, ok, but can statistician predict the future using the history repeats itself assumption? } 3. Some products permit little learning from past mistakes.

{My understanding: Even when people can learn from past mistakes in the financial markets, we can always make different mistakes.}

Read more (about how not to exploit continuously the fact that the others are stupid) at N umber 2. Again, it is an excellent paper. I love Figure 5 especially what describes the MARKET It has never crossed my mind that we can describe the market in this way:

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |3

Also What is Intraday Liquidity Risk? We have the official definition from the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) Intraday Liquidity Risk is the risk that a bank fails to manage its intraday liquidity effectively, which could leave it unable to meet a payment obligation at the time expected, thereby affecting its own liquidity position and that of other parties. Yes, we have a final rule, the introduction of monitoring tools for intraday liquidity. Under Pillar 2.

Why Pillar 2?

According to the paper (at N umber 1 below), the tools are being introduced for monitoring purposes only.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |4

Internationally active banks will be required to apply these tools. National supervisors will determine the extent to which the tools apply to non-internationally active banks within their jurisdictions. However, banks and supervisors are not required to disclose these reporting requirements publicly. Public disclosure is not intended to be part of these monitoring tools.

For the eyes of the supervisors only Pillar 2 these Basel iii secrets

But also:

National supervisors will determine the extent Another national discretion another opportunity to say bye-bye harmonized approach to implement Basel I I I . Read more at Number 1 below. Welcome to the Top 10 list.

Best Regards,

George Lekatis President of the I ARCP General Manager, Compliance LLC 1200 G Street N W Suite 800, Washington DC 20005, USA Tel: (202) 449-9750 Email: lekatis@risk-compliance-association.com Web: www.risk-compliance-association.com HQ: 1220 N. Market Street Suite 804, Wilmington DE 19801, USA Tel: (302) 342-8828

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |5

BIS: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)

Monitoring tools for intraday liquidity management - final document, April 2013

This document is the final version of the Committee's Monitoring tools for intraday liquidity management. It was developed in consultation with the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems to enable banking supervisors to better monitor a bank's management of intraday liquidity risk and its ability to meet payment and settlement obligations on a timely basis.

Applying behavioural economics at the Financial Conduct Authority

April 2013

Kristine Erta, Stefan H unt, Zanna I scenko, Will Brambley A rapidly growing literature on behavioural economics shows that some errors made by consumers are persistent and predictable. This raises the prospect of firms designing business models that do not focus on competing on price and quality. Behavioural economics enables regulators to intervene in markets more effectively, and in new ways, to counter such business models and secure better outcomes for consumers.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |6

Thematic peer review on the FSB Principles for Reducing Reliance on Credit Rating Agency (CRA) Ratings

The goal of the Principles is to end mechanistic reliance on CRA ratings by banks, institutional investors and other market participants.

Stress testing banks what have we learned?

Speech by Mr Ben S Bernanke, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, at the Maintaining financial stability: holding a tiger by the tail financial markets conference, sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Stone Mountain, Georgia

APRA releases consultation package on disclosure of composition of capital and remuneration

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) today released a consultation paper and draft prudential standard relating to Pillar 3 disclosures on the composition of capital and on remuneration by authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) in Australia.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |7

ESMA 2013 Regulatory Work Programme

ESMA has published its 2013 Regulatory Work Programme which is based on its 2013 Work Programme, published in October 2012, and provides a detailed breakdown of the of the individual workstreams as outlined in the 2013 Work Programme.

Islamic finance and the European challenge

Opening address by Mr Ignazio Visco, Governor of the Bank of I taly, at the IFSB Forum The European challenge, organized by the I slamic Financial Services Board (IFSB) and hosted by the Bank of Italy, Rome, 9 April 2013.

COMMODITY FUTURES TRADING COMMISSION, SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION

Identity Theft Red Flags Rules

Joint final rules and guidelines.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |8

Department of H ome Affairs SUMMARY OF RESPONSES TO TH E CONSULTATI ON ON TH E MONEY LAUNDERING AND TERRORIST FINAN CING CODE 2013

The Department of Home Affairs (DHA) issued the Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Code 2013 with a view to replacing the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) Code 2010 and the Prevention of Terrorist Financing Code 2011.

Regulation of Cross-Border OTC Derivatives Activities: Finding the Middle Ground

By Chairman Elisse Walter, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, American Bar Association Spring Meeting, Washington D.C.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

Page |9

BIS: Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS)

Monitoring tools for intraday liquidity management - final document, April 2013

This document is the final version of the Committee's Monitoring tools for intraday liquidity management. It was developed in consultation with the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems to enable banking supervisors to better monitor a bank's management of intraday liquidity risk and its ability to meet payment and settlement obligations on a timely basis. Over time, the tools will also provide supervisors with a better understanding of banks' payment and settlement behaviour. The framework includes: the detailed design of the monitoring tools for a bank's intraday liquidity risk stress scenarios key application issues the reporting regime Management of intraday liquidity risk forms a key element of a bank's overall liquidity risk management framework. As such, the set of seven quantitative monitoring tools will complement the qualitative guidance on intraday liquidity management set out in the Basel Committee's 2008 Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 10

It is important to note that the tools are being introduced for monitoring purposes only and that internationally active banks will be required to apply them.

National supervisors will determine the extent to which the tools apply to non-internationally active banks within their jurisdictions. Basel I I I: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools (January 2013), which sets out one of the Committee's key reforms to strengthen global liquidity regulations does not include intraday liquidity within its calibration. The reporting of the monitoring tools will commence on a monthly basis from 1 January 2015 to coincide with the implementation of the LCR reporting requirements. An earlier version of the framework of monitoring tools was issued for consultation in July 2012. The Committee wishes to thank those who provided feedback and comments as these were instrumental in revising and finalising the monitoring tools.

Monitoring tools for intraday liquidity management April 2013 Introduction

1. Management of intraday liquidity risk forms a key element of a banks overall liquidity risk management framework. In September 2008, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) published its Principles for Sound Liquidity Risk Management and Supervision (the Sound Principles), which provide guidance for banks on their management of liquidity risk and collateral. Principle 8 of the Sound Principles focuses specifically on intraday liquidity risk and states that:

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 11

A bank should actively manage its intraday liquidity positions and risks to meet payment and settlement obligations on a timely basis under both normal and stressed conditions and thus contribute to the smooth functioning of payment and settlement systems.

2. Principle 8 identifies six operational elements that should be included in a banks strategy for managing intraday liquidity risk. These state that a bank should: (i)have the capacity to measure expected daily gross liquidity inflows and outflows, anticipate the intraday timing of these flows where possible, and forecast the range of potential net funding shortfalls that might arise at different points during the day; (ii)have the capacity to monitor intraday liquidity positions against expected activities and available resources (balances, remaining intraday credit capacity, available collateral); (iii)arrange to acquire sufficient intraday funding to meet its intraday objectives; (iv)have the ability to manage and mobilise collateral as necessary to obtain intraday funds; (v)have a robust capability to manage the timing of its liquidity outflows in line with its intraday objectives; and (vi)be prepared to deal with unexpected disruptions to its intraday liquidity flows. 3.In January 2013, the BCBS published Basel I I I: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and liquidity risk monitoring tools, which sets out one of the Committees key reforms to strengthen global liquidity regulations. The objective of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) is to promote the short-term resilience of the liquidity risk profile of banks, but does not include intraday liquidity within its calibration. 4.The BCBS, in consultation with the Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems (CPSS) has developed a set of quantitative tools to enable banking supervisors to monitor banks intraday liquidity risk and

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 12

their ability to meet payment and settlement obligations on a timely basis under both normal and stressed conditions.

The monitoring tools will complement the qualitative guidance in the Sound Principles. 5. Given the close relationship between the management of banks intraday liquidity risk and the smooth functioning of payment and settlement systems, 4 the tools will also be of benefit to central bank or other authorities responsible for the oversight of payment and settlement systems (overseers). It is envisaged that the introduction of monitoring tools for intraday liquidity will lead to closer co-operation between banking supervisors and the overseers in the monitoring of banks payment behaviour. 6.It is important to note that the tools are being introduced for monitoring purposes only. Internationally active banks will be required to apply these tools. These tools may also be useful in promoting sound liquidity management practices for other banks, whether they are direct participants of a large-value payment system (LVPS) or use a correspondent bank to settle payments. National supervisors will determine the extent to which the tools apply to non-internationally active banks within their jurisdictions. 7.Consistent with their broader liquidity risk management responsibilities, bank management will be responsible for collating and submitting the monitoring data for the tools to their banking supervisor. It is recognised that banks may need to liaise closely with counterparts, including payment system operators and correspondent banks, to collate these data.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 13

However, banks and supervisors are not required to disclose these reporting requirements publicly.

Public disclosure is not intended to be part of these monitoring tools. 8. The following sections of this document set out: The definitions of intraday liquidity and intraday liquidity risk and the elements that constitute a banks intraday liquidity sources and usage The detailed design of the intraday liquidity monitoring tools The intraday liquidity stress scenarios The scope of application of the tools The implementation date and reporting frequency

I I . Definitions and sources and usage of intraday liquidity A. Definitions

9. For the purpose of this document, the following definitions will apply to the terms stated below. Intraday Liquidity: funds which can be accessed during the business day, usually to enable banks to make payments in real time Business Day: the opening hours of the LVPS or of correspondent banking services during which a bank can receive and make payments in a local jurisdiction Intraday Liquidity Risk: the risk that a bank fails to manage its intraday liquidity effectively, which could leave it unable to meet a payment obligation at the time expected, thereby affecting its own liquidity position and that of other parties.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 14

Time-specific obligations: obligations which must be settled at a specific time within the day or have an expected intraday settlement deadline.

B. I ntraday liquidity sources and usage

10. The following sets out the main constituent elements of a banks intraday liquidity sources and usage. (The list should not be taken as exhaustive.) (i) Sources

Own sources Reserve balances at the central bank; Collateral pledged with the central bank or with ancillary systems that can be freely converted into intraday liquidity; Unencumbered assets on a banks balance sheet that can be freely converted into intraday liquidity; Secured and unsecured, committed and uncommitted credit lines available intraday; Balances with other banks that can be used for intraday settlement. Other sources Payments received from other LVPS participants; Payments received from ancillary systems; Payments received through correspondent banking services.

(ii) Usage Payments made to other LVPS participants; Payments made to ancillary systems; Payments made through correspondent banking services; Secured and unsecured, committed and uncommitted credit lines offered intraday; Contingent payments relating to a payment and settlement systems failure (eg as an emergency liquidity provider).

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 15

1 1. I n correspondent banking, some customer payments are made across accounts held by the same correspondent bank.

These payments do not give rise to an intraday liquidity source or usage for the correspondent bank as they do not link to the payment and settlement systems. However, these internalised payments do have intraday liquidity implications for both the sending and receiving customer banks and should be incorporated in their reporting of the monitoring tools.

I I I. The intraday liquidity monitoring tools

12. A number of factors influence a banks usage of intraday liquidity in payment and settlement systems and its vulnerability to intraday liquidity shocks. As such, no single monitoring tool can provide supervisors with sufficient information to identify and monitor the intraday liquidity risk run by a bank.

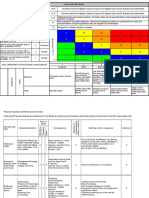

To achieve this, seven separate monitoring tools have been developed (see Table 1).

As not all of the tools will be relevant to all reporting banks, the tools have been classified in three groups to determine their applicability as follows: Category A: applicable to all reporting banks; Category B: applicable to reporting banks that provide correspondent banking services; and Category C: applicable to reporting banks which are direct participants.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 16

A. Monitoring tools applicable to all reporting banks (i) Daily maximum intraday liquidity usage

13. This tool will enable supervisors to monitor a banks intraday liquidity usage in normal conditions. It will require banks to monitor the net balance of all payments made and received during the day over their settlement account, either with the central bank (if a direct participant) or over their account held with a correspondent bank (or accounts, if more than one correspondent bank is used to settle payments). The largest net negative position during the business day on the account(s), (ie the largest net cumulative balance between payments made and received), will determine a banks maximum daily intraday liquidity usage. The net position should be determined by settlement time stamps (or the equivalent) using transaction-by-transaction data over the account(s). The largest net negative balance on the account(s) can be calculated after close of the business day and does not require real-time monitoring throughout the day.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 17

14. For illustrative purposes only, the calculation of the tool is shown in figure 1.

A positive net position signifies that the bank has received more payments than it has made during the day. Conversely, a negative net position signifies that the bank has made more payments than it has received. For direct participants, the net position represents the change in its opening balance with the central bank. For banks that use one or more correspondent banks, the net position represents the change in the opening balance on the account(s) with its correspondent bank(s).

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 18

15.Assuming that a bank runs a negative net position at some point intraday, it will need access to intraday liquidity to fund this balance.

The minimum amount of intraday liquidity that a bank would need to have available on any given day would be equivalent to its largest negative net position. (In the illustration above, the intraday liquidity usage would be 10 units.) 16.Conversely, when a bank runs a positive net cumulative position at some point intraday, it has surplus liquidity available to meet its intraday liquidity obligations. This position may arise because the bank is relying on payments received from other LVPS participants to fund its outgoing payments. (In the illustration above, the largest positive net cumulative position would be 8.6 units.) 17.Banks should report their three largest daily negative net cumulative positions on their settlement or correspondent account(s) in the reporting period and the daily average of the negative net cumulative position over the period. The largest positive net cumulative positions, and the daily average of the positive net cumulative positions, should also be reported. As the reporting data accumulates, supervisors will gain an indication of the daily intraday liquidity usage of a bank in normal conditions.

(ii) Available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day

18. This tool will enable supervisors to monitor the amount of intraday liquidity a bank has available at the start of each day to meet its intraday liquidity requirements in normal conditions.

Banks should report both the three smallest sums by value of intraday liquidity available at the start of each business day in the reporting period,

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 19

and the average amount of available intraday liquidity at the start of each business day in the reporting period.

The report should also break down the constituent elements of the liquidity sources available to the bank. 19.Drawing on the liquidity sources set out in Section I I B above, banks should discuss and agree with their supervisor the sources of liquidity which they should include in the calculation of this tool. Where banks manage collateral on a cross-currency and/ or cross-system basis, liquidity sources not denominated in the currency of the intraday liquidity usage and/ or which are located in a different jurisdiction, may be included in the calculation if the bank can demonstrate to the satisfaction of its supervisor that the collateral can be transferred intraday freely to the system where it is needed. 20.As the reporting data accumulates, supervisors will gain an indication of the amount of intraday liquidity available to a bank to meet its payment and settlement obligations in normal conditions.

(iii) Total payments

21. This tool will enable supervisors to monitor the overall scale of a banks payment activity. For each business day in a reporting period, banks should calculate the total of their gross payments sent and received in the LVPS and/ or, where appropriate, across any account(s) held with a correspondent bank(s). Banks should report the three largest daily values for gross payments sent and received in the reporting period and the average daily figure of gross payments made and received in the reporting period.

(iv) Time-specific obligations

22. This tool will enable supervisors to gain a better understanding of a banks time specific obligations.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 20

Failure to settle such obligations on time could result in financial penalty, reputational damage to the bank or loss of future business.

23. Banks should calculate the total value of time-specific obligations that they settle each day and report the three largest daily total values and the average daily total value in the reporting period to give supervisors an indication of the scale of these obligations.

B. Monitoring tools applicable to reporting banks that provide correspondent banking services (i) Value of payments made on behalf of correspondent banking customers

24.This tool will enable supervisors to gain a better understanding of the proportion of a correspondent banks payment flows that arise from its provision of correspondent banking services. These flows may have a significant impact on the correspondent banks own intraday liquidity management.

25.Correspondent banks should calculate the total value of payments they make on behalf of all customers of their correspondent banking services each day and report the three largest daily total values and the daily average total value of these payments in the reporting period.

(ii) Intraday credit lines extended to customers

26. This tool will enable supervisors to monitor the scale of a correspondent banks provision of intraday credit to its customers.

Correspondent banks should report the three largest intraday credit lines extended to their customers in the reporting period, including whether these lines are secured or committed and the use of those lines at peak usage.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 21

C. Monitoring tool applicable to reporting banks which are direct participants

(i) I ntraday throughput

27. This tool will enable supervisors to monitor the throughput of a direct participants daily payments activity across its settlement account. Direct participants should report the daily average in the reporting period of the percentage of their outgoing payments (relative to total payments) that settle by specific times during the day, by value within each hour of the business day. Over time, this will enable supervisors to identify any changes in a banks payment and settlement behaviour.

IV. Intraday liquidity stress scenarios

28.The monitoring tools in Section I I I will provide banking supervisors with information on a banks intraday liquidity profile in normal conditions. However, the availability and usage of intraday liquidity can change markedly in times of stress. In the course of their discussions on broader liquidity risk management, banks and supervisors should also consider the impact of a banks intraday liquidity requirements in stress conditions. As guidance, four possible (but non-exhaustive) stress scenarios have been identified and are described below. Banks should determine with their supervisor which of the scenarios are relevant to their particular circumstances and business model. 29.Banks need not report the impact of the stress scenarios on the monitoring tools to supervisors on a regular basis.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 22

They should use the scenarios to assess how their intraday liquidity profile in normal conditions would change in conditions of stress and discuss with their supervisor how any adverse impact would be addressed either through contingency planning arrangements and/ or their wider intraday liquidity risk management framework.

Stress scenarios (i) Own financial stress: a bank suffers, or is perceived to be suffering from, a stress event

30.For a direct participant, own financial and/ or operational stress may result in counterparties deferring payments and/ or withdrawing intraday credit lines. This, in turn, may result in the bank having to fund more of its payments from its own intraday liquidity sources to avoid having to defer its own payments. 31.For banks that use correspondent banking services, an own financial stress may result in intraday credit lines being withdrawn by the correspondent bank(s), and/ or its own counterparties deferring payments. This may require the bank having either to prefund its payments and/ or to collateralise its intraday credit line(s).

(ii) Counterparty stress: a major counterparty suffers an intraday stress event which prevents it from making payments

32. A counterparty stress may result in direct participants and banks that use correspondent banking services being unable to rely on incoming payments from the stressed counterparty , reducing the availability of intraday liquidity that can be sourced from the receipt of the counterpartys payments.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 23

(iii) A customer banks stress: a customer bank of a correspondent bank suffers a stress event

33. A customer banks stress may result in other banks deferring payments to the customer, creating a further loss of intraday liquidity at its correspondent bank.

(iv) Market-wide credit or liquidity stress

34.A market-wide credit or liquidity stress may have adverse implications for the value of liquid assets that a bank holds to meet its intraday liquidity usage. A widespread fall in the market value and/ or credit rating of a banks unencumbered liquid assets may constrain its ability to raise intraday liquidity from the central bank. In a worst case scenario, a material credit downgrade of the assets may result in the assets no longer meeting the eligibility criteria for the central banks intraday liquidity facilities.

35.For a bank that uses correspondent banking services, a widespread fall in the market value and/ or credit rating of its unencumbered liquid assets may constrain its ability to raise intraday liquidity from its correspondent bank(s).

36.Banks which manage intraday liquidity on a cross-currency basis should consider the intraday liquidity implications of a closure of, or operational difficulties in, currency swap markets and stresses occurring in multiple systems simultaneously.

Application of the stress scenarios

37.For the own financial stress and counterparty stress, all reporting banks should consider the likely impact that these stress scenarios would have on their daily maximum intraday liquidity usage, available intraday

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 24

liquidity at the start of the business day, total payments and time-specific obligations.

38.For the customer banks stress scenario, banks that provide correspondent banking services should consider the likely impact that this stress scenario would have on the value of payments made on behalf of its customers and intraday credit lines extended to its customers. 39.For the market-wide stress, all reporting banks should consider the likely impact that the stress would have on their sources of available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day. 40.While each of the monitoring tools has value in itself, combining the information provided by the tools will give supervisors a comprehensive view of a banks resilience to intraday liquidity shocks. Examples on how the tools could be used in different combinations by banking supervisors to assess a banks resilience to intraday liquidity risk are presented in Annex 3.

V. Scope of application

41. Banks generally manage their intraday liquidity risk on a system-by-system basis in a single currency, but it is recognised that practices differ across banks and jurisdictions, depending on the institutional set up of a bank and the specifics of the systems in which it operates. The following considerations aim to help banks and supervisors determine the most appropriate way to apply the tools. Should banks need further clarification, they should discuss the scope of application with their supervisors.

(i) Systems

42. Banks which are direct participants to an LVPS can manage their intraday liquidity in very different ways.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 25

Some banks manage their payment and settlement activity on a system-by-system basis.

Others make use of direct intraday liquidity bridges between LVPS, which allow excess liquidity to be transferred from one system to another without restriction. Other formal arrangements exist, which allow funds to be transferred from one system to another (such as agreements for foreign currency liquidity to be used as collateral for domestic systems). 43. To allow for these different approaches, direct participants should apply a bottom-up approach to determine the appropriate basis for reporting the monitoring tools. The following sets out the principles which such banks should follow: As a baseline, individual banks should report on each LVPS in which they participate on a system-by-system-basis; I f there is a direct real-time technical liquidity bridge between two or more LVPS, the intraday liquidity in those systems may be considered fungible. At least one of the linked LVPS may therefore be considered an ancillary system for the purpose of the tools; I f a bank can demonstrate to the satisfaction of its supervisor that it regularly monitors positions and uses other formal arrangements to transfer liquidity intraday between LVPS which do not have a direct technical liquidity bridge, those LVPS may also be considered as ancillary systems for reporting purposes. 44. Ancillary systems (eg retail payment systems, CLS, some securities settlement systems and central counterparties), place demands on a banks intraday liquidity when these systems settle the banks obligations in an LVPS.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 26

Consequently, separate reporting requirements will not be necessary for such ancillary systems.

45.Banks that use correspondent banking services should base their reports on the payment and settlement activity over their account(s) with their correspondent bank(s). Where more than one correspondent bank is used, the bank should report per correspondent bank. For banks which access an LVPS indirectly through more than one correspondent bank, the reporting may be aggregated, provided that the reporting bank can demonstrate to the satisfaction of its supervisor that it is able to move liquidity between its correspondent banks. 46.Banks which operate as direct participants of an LVPS but which also make use of correspondent banks should discuss whether they can aggregate these for reporting purposes with their supervisor. Aggregation may be appropriate if the payments made directly through the LVPS and those made through the correspondent bank(s) are in the same jurisdiction and same currency.

(ii) Currency

47.Banks that manage their intraday liquidity on a currency-by-currency basis should report on an individual currency basis. 48.If a bank can prove to the satisfaction of its supervisor that it manages liquidity on a cross-currency basis and has the ability to transfer funds intraday with minimal delay including in periods of acute stress then the intraday liquidity positions across currencies may be aggregated for reporting purposes. However, banks should also report at an individual currency level so that supervisors can monitor the extent to which firms are reliant on foreign exchange swap markets.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 27

49. When the level of activity of a banks payment and settlement activity in any one particular currency is considered de minimis with the agreement of the supervisor23 a reporting exemption could apply and separate returns need not be submitted.

(iii) Organisational structure

50.The appropriate organisational level for each banks reporting of its intraday liquidity data should be determined by the supervisor, but it is expected that the monitoring tools will typically be applied at a significant individual legal entity level. The decision on the appropriate entity should consider any potential impediments to moving intraday liquidity between entities within a group, including the ability of supervisory jurisdictions to ring-fence liquid assets, timing differences and any logistical constraints on the movement of collateral. 51.Where there are no impediments or constraints to transferring intraday liquidity between two (or more) legal entities intraday, and banks can demonstrate this to the satisfaction of their supervisor, the intraday liquidity requirements of the entities may be aggregated for reporting purposes.

(iv) Responsibility of home and host supervisors

52. For cross-border banking groups, where a bank operates in LVPS and/ or with a correspondent bank(s) outside the jurisdiction where it is domiciled, both home and host supervisors will have an interest in ensuring that the bank has sufficient intraday liquidity to meet its obligations in the local LVPS and/ or with its correspondent bank(s). The allocation of responsibility between home and host supervisor will ultimately depend upon whether the bank operating in the non-domestic jurisdiction does so via a branch or a subsidiary.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 28

For a branch operation

The home (consolidated) supervisor should have responsibility for monitoring through the collection and examination of data that its banking groups can meet their payment and settlement responsibilities in all countries and all currencies in which they operate. The home supervisor should therefore have the option to receive a full set of intraday liquidity information for its banking groups, covering both domestic and non-domestic payment and settlement obligations. The host supervisor should have the option to require foreign branches in their jurisdiction to report intraday liquidity tools to them, subject to materiality.

For a subsidiary active in a non-domestic LVPS and/ or correspondent bank(s)

The host supervisor should have primary responsible for receiving the relevant set of intraday liquidity data for that subsidiary.

The supervisor of the parent bank (the home consolidated supervisor) will have an interest in ensuring that a non-domestic subsidiary has sufficient intraday liquidity to participate in all payment and settlement obligations.

The home supervisor should therefore have the option to require non-domestic subsidiaries to report intraday liquidity data to them as appropriate.

VI. Implementation date and reporting frequency

53.The reporting of the monitoring tools will commence on a monthly basis from 1 January 2015 to coincide with the implementation of the LCR reporting requirements. 54. Sample reporting templates can be found in Annex 2.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 29

As noted above, the tools apply to internationally active banks.

National supervisors will determine whether other banks should apply the reporting requirements. Banks should also agree with their supervisors the scope of application and reporting arrangements between home and host authorities. 55. If customer banks are unable to meet this implementation deadline because of data availability constraints with their correspondent bank(s), consideration may be given by supervisors to phasing-in their implementation to a later date (preferably no later than 1 January 2017).

Annex 1 Practical example of the monitoring tools

The following example illustrates how the tools would operate for a bank on a particular business day. Assume that on the given day, the banks payment profile and liquidity usage is as follows:

1. Direct participant Details of the banks payment profile are as followings:

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 30

Payment A: 450 Payment B: 100 to settle obligations in an ancillary system Payment C: 200 which has to be settled by 10 am Payment D: 300 on behalf of a counterparty using some of a 500 unit unsecured credit line that the bank extends to the counterparty Payment E: 250 Payment F: 100 The bank has 300 units of central bank reserves and 500 units of eligible collateral.

A(i) Daily maximum liquidity usage: largest negative net cumulative positions: 550 units largest positive net cumulative positions: 200 units A(ii) Available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day: 300 units of central bank reserves + 500 units of eligible collateral (routinely transferred to the central bank) = 800 units A(iii) Total payments: Gross payments sent: 450+100+200+300+250+100 = 1,400 units Gross payments received: 200+400+300+350+150 = 1,400 units A(iv) Time-specific obligations: 200 + value of ancillary payment (100) = 300 units B(i) Value of payments made on behalf of correspondent banking customers: 300 units B(ii) Intraday credit line extended to customers: Value of intraday credit lines extended: 500 units Value of credit line used: 300 units C(i) Intraday throughput

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 31

2. Bank that uses a correspondent bank Details of the banks payment profile are as followings: Payment A: 450 Payment B: 100 Payment C: 200 which has to be settled by 10am Payment D: 300 Payment E: 250 Payment F: 100 which has to be settled by 4pm The bank has 300 units of account balance at the correspondent bank and 500 units of credit lines of which 300 units unsecured and also uncommitted. A(i) Daily maximum intraday liquidity usage: largest negative net cumulative positions: 550 units largest positive net cumulative positions: 200 units A(ii) Available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day: 300 units of account balance at the correspondent bank + 500 units of credit lines (of which 300 units unsecured and uncommitted) = 800 units A(iii) Total payments: Gross payments sent: 450+100+200+300+250+100 = 1,400 units Gross payments received: 200+400+300+350+150 = 1,400 units

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 32

A(iv) Time-specific obligations: 200 + 100 = 300 units

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 33

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 34

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 35

Annex 3 Combining the tools

The following is a non-exhaustive set of examples which illustrate how the tools could be used in different combinations by supervisors to assess a banks resilience to intraday liquidity risk:

(1)Time-specific obligations relative to total payments and available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day If a high proportion of a banks payment activity is time critical, the bank has less flexibility to deal with unexpected shocks by managing its payment flows, especially when its amount of available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day is typically low. In such circumstances the supervisor might expect the bank to have adequate risk management arrangements in place or to hold a higher proportion of unencumbered assets to mitigate this risk. (2)Available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day relative to the impact of intraday stresses on the banks daily liquidity usage If the impact of an intraday liquidity stress on a banks daily liquidity usage is large relative to its available intraday liquidity at the start of the

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 36

business day, it suggests that the bank may struggle to settle payments in a timely manner in conditions of stress.

(3)Relationship between daily maximum liquidity usage, available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day and the time-specific obligations If a bank misses its time-specific obligations, it could have a significant impact on other banks. If it were demonstrated that the banks daily liquidity usage was high and the lowest amount of available intraday liquidity at the start of the business day were close to zero, it might suggest that the bank is managing its payment flows with an insufficient pool of liquid assets. (4)Total payments and value of payments made on behalf of correspondent banking customers If a large proportion of a banks total payment activity is made by a correspondent bank on behalf of its customers and, depending on the type of the credit lines extended, the correspondent bank could be more vulnerable to a stress experienced by a customer. The supervisor may wish to understand how this risk is being mitigated by the correspondent bank. (5) Intraday throughput and daily liquidity usage: If a bank starts to defer its payments and this coincides with a reduction in its liquidity usage (as measured by its largest positive net cumulative position), the supervisor may wish to establish whether the bank has taken a strategic decision to delay payments to reduce its usage of intraday liquidity. This behavioural change might also be of interest to the overseers given the potential knock-on implications to other participants in the LVPS.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 37

Applying behavioural economics at the Financial Conduct Authority

April 2013 Kristine Erta, Stefan H unt, Zanna I scenko, Will Brambley A rapidly growing literature on behavioural economics shows that some errors made by consumers are persistent and predictable. This raises the prospect of firms designing business models that do not focus on competing on price and quality. Behavioural economics enables regulators to intervene in markets more effectively, and in new ways, to counter such business models and secure better outcomes for consumers. The UK Parliament has created the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) and has given it an additional objective and duty to promote effective competition, which we believe should be on price and quality (rather than on false focal points or strategies to exclude rivals at point-of-sale).

To achieve this, the FCA will first need to undertake integrated analysis of economic markets.

In other words, it will need to understand how information problems, consumers behavioural errors and firms competitive strategies combine to produce observed market outcomes. This involves some change from the existing practice of most conduct regulators, with one of the biggest changes relating to greater focus on understanding consumer behaviour. This paper first sets out what behavioural economics tells us about consumer decision-making in financial markets. This is based on an extensive review of the available literature.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 38

It then discusses how behavioural economics can be, and should be, used in the regulation of financial conduct.

While I recognise that this is an independent piece of research, this paper is the first in the Financial Conduct Authoritys Occasional Paper series, and an important one at that. I therefore add my support for the paper. I believe that using insights from behavioural economics, together with more traditional analysis of competition and market failures, can help the FCA assess problems in financial markets better, choose more appropriate remedies and be a more effective regulator as a result. While applying behavioural economics also brings new challenges, I believe they are surmountable.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 39

Executive summary

People often make errors when choosing and using financial products, and can suffer considerable losses as a result. Using behavioural economics we can understand how these errors arise, why they persist, and what we can do to ameliorate them. Behavioural economics uses insights from psychology to explain why people behave the way they do. People do not always make choices in a rational and calculated way. In fact, most human decision-making uses thought processes that are intuitive and automatic rather than deliberative and controlled. Academic literature identifies behavioural biasesspecific ways in which normal human thought systematically departs from being fully rational. Biases can cause people to misjudge important facts or to be inconsistent, for example changing their choices for the worse when essentially the same decision is presented in a different way. In other words, our normal human thought processes can lead us to make choices that are predictably mistaken. Market forces left to themselves will often not work to reduce these mistakes, so regulation may be needed. A good example is payment protection insurance (PPI).

Firms were able to earn large profits on PPI products because many buyers fundamentally misunderstood PPI pricing and the limitations in its coverage.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 40

High PPI prices allowed sellers to attract more customers by offering mortgages at cheaper rates (which consumers focused on when choosing a provider).

As a result, no firm had an incentive to advertise that PPI was a poor product for many people and charge appropriate mortgage and PPI prices. This would have made the firms mortgage more expensive and the firm uncompetitive.

Intervention was needed to solve this problem.

While it is common sense that people make mistakes, behavioural economics takes us beyond intuition and helps us be precise in detecting, understanding, and remedying problems that arise from consumer mistakes. Integrating behavioural economics into the FCA can therefore help it be an effective regulator. This paper has two parts. In Part I we summarise the main lessons from behavioural economics for retail financial markets: - how consumers make predictable mistakes when choosing and using financial products; - how firms respond to these mistakes, and - how behavioural biases can lead firms to compete in ways that are not in the interests of consumers. In Part I I we describe how behavioural economics can, and should, be used in the regulation of financial conduct.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 41

Part I: Lessons from behavioural economics

Why are there more behavioural problems in financial services?

For a number of reasons, consumer choice in retail financial products and services is particularly prone to errors: Many products are inherently complex for most people. Financial products are abstract and intangible and often have many features and complex charging structures. This contrasts with many ordinary products where consumers can easily understand what they are getting and the product has a single, simple price. Faced with complexity, consumers can simplify decisions in ways that lead to errors, such as focusing only on headline rates. Many products involve trade-offs between the present and the future. Often people make decisions against their long-term interests because of self-control problems, e.g. borrowing excessively using payday loans. Decisions may require assessing risk and uncertainty. People are generally bad (even terrible) intuitive statisticians and are prone to making systematic errors in decisions involving uncertainty. So we often misjudge probabilities and make poor insurance or investment decisions. Decisions can be emotional. Stress, anxiety, fear of losses and regret, rather than the costs and benefits of the choices, can drive decisions.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 42

Some products permit little learning from past mistakes.

Some financial decisions, such as choosing a retirement plan or mortgage, are made infrequently, with little learning from others, and with consequences revealed only after a long delay.

Which biases affect consumer financial decisions?

To identify and correct mistakes we need to be able to detect biases. The table below lists the most relevant biases for retail markets, categorising biases according to how they affect decisions: preferences (what we want); beliefs (what we believe are the facts about our situation and options); and decision-making (which option gets us closest to what we want, given our beliefs).

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 43

Categorising biases like this helps us consider whether people are making mistakes.

Errors in beliefs or decision-making can often be clear-cut.

For example, people may have beliefs about the likelihood of an event that contradicts objective probabilities. But if peoples preferences are inconsistent (and so not fully rational), it can be difficult to say that these preferences are wrong; they are after all what people want, at least at the time.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 44

If people are not making mistakes, intervening to prevent them from acting on these preferences can make them worse-off.

How do biases affect the strategies of firms, competition and other market problems?

Firms play a crucial role in shaping consumer choices. Product design, marketing or sales processes can exacerbate the effects of biases and cause problems.

Firms can respond to the different biases in specific ways (we give detailed examples in the Annex).

One important response is that firms will tend to increase non-salient prices and decrease salient prices. For example, if consumers tend to underestimate how much they will spend on their credit card in the future (because of projection bias or overconfidence), firms have an incentive to offer low rates today with higher rates later. Another important response is that firms will tend to obfuscate unattractive product attributes, such as exclusions in insurance contracts. Consumer biases thus affect competition. They can lead firms to compete in ways that are not in consumer interests, e.g. by offering products that appeal to the consumer because they play to biases. Biases can also create de facto market power in markets that might appear competitive based on the number of firms alone. We must be mindful, however, that sometimes firms might not know that their customers are making mistakes.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 45

What looks like deliberate exploitation may actually just be firms responding to observed consumer demand without realising that it is driven by biases.

Regardless of what firms know, in badly functioning markets bias exploitation may be the only way for firms to attract and retain consumers and therefore to stay in business. Behavioural biases can also interact with other market failures like information asymmetries or externalities.

They can exacerbate other problems or make regulatory interventions aimed at addressing problems ineffective or even harmful.

Part I I : Applying behavioural economics at the FCA

We have already begun to put behavioural economics into practice, but change will not be instantaneous. Behavioural economics raises important issues for all steps of the regulatory process.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 46

Step 1: Identifying and prioritising issues

How can we spot potential consumer detriment caused by biases?

Biases are rarely directly observable. Based on evidence on the common mistakes people make, we suggest a set of indicators that can help identify where consumer detriment from mistakes may be particularly high. The indicators highlight potentially problematic consumer and firm behaviours and product features. A complementary approach to detecting issues is to identify the true economic function of a product and then evaluate whether consumers actually use the product for this function, or for another reason.

How can we prioritise these risks?

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 47

We will prioritise risks arising from behavioural biases as with other issues.

Size of the problem will obviously drive priority. Behavioural problems can cause less sophisticated consumers to pay more than others, effectively cross-subsidising the more sophisticated, so prioritisation also needs to consider these distributional effects.

Step 2: Understanding root causes of problems

Could consumers be choosing reasonably? If consumers are biased, what do they truly want and need?

When analysing problems we need to develop possible explanations as to the underlying cause and then build evidence. We must investigate whether consumers are making mistakes, and if so which biases may be the cause. Crucial evidence includes how consumers choose in different settings (e.g. do consumers choose differently as they gain experience?), their awareness of essential product information and their self-reported needs and objectives.

How should we analyse firm-specific issues?

For firm-specific issues, behavioural insights can inform what dialogue to have with, and what information to gather from the firm. Qualitative information may be enough, though data on consumer behaviour may be needed. Establishing whether the product feature or practice is common to many firms or market-wide is important.

How should we analyse market-wide issues?

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 48

Diagnosing market-wide issues naturally requires a greater level of evidence.

This may include collecting first-hand data using consumer research, laboratory experiments or field experiments (also called randomised controlled trials, or RCTs). Analysis must consider the broad context of the market, including how firms compete, what other market and regulatory failures are present and how consumer biases interact with these factors.

Step 3: Designing effective interventions

What interventions are available to protect consumers?

Behavioural economics offers new perspectives on interventions that the FCA could use, for behavioural and other problems in the market. Ordered from least to most interventionist, there are four ways in which the FCA could solve behavioural problems:

1.Provide information. Require firms to provide information in a specific way or prohibit specific marketing materials or practices.

2.Change the choice environment. Adjust how choices are presented to consumers. 3.Control product distribution. Require products to be promoted or sold only through particular channels or only to certain types of clients. 4.Control products. Ban specific product features or whole products that appear designed to exploit, or require products to contain specific features. We could expand our toolkit by using more nudges small prompts that, if designed well, have low costs and can lead to better decisions by biased consumers without restricting choice.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 49

Providing information or changing the choice environment can be nudges.

As these less interventionist measures do not constrain consumer choice, they are preferable, if they are effective in preventing mistakes. Understanding how consumers make decisions can also improve the effectiveness of traditional remedies, such as disclosure. Consumer psychology is nuanced, however, and specific interventions can succeed or fail based on small details. Interventions should therefore ideally be tested in practice before implementation, possibly using RCTs. Often consumer biases are just one part of a problem, and a package of market-wide measures will be required.

Should we intervene and, if so, how? How can we assess the impact of interventions?

Applying behavioural economics also brings additional challenges.

We will have to tackle difficult questions like: what is in consumers best interests, where should the limits to consumer responsibility lie, and how effective are less interventionist measures, such as nudges, or more interventionist measures, such as product banning? When choosing between different measures, or no intervention at all, we need to assess their costs and benefits, to the extent that this is practically possible.

A wide variety of factors should be considered including

(i) whether firms can circumvent the measure, (ii) negative and positive impacts on innovation,

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 50

(iii)transfers between different groups of consumers, e.g. the more and the less sophisticated,

(iv) the impact on consumers incentives to learn and (v)whether the problem is one for the regulator or best left to the Government. Traditional impact assessment approaches, for example, for estimating benefits to consumers, may need to be adapted when biases are present.

Conclusion

Integrating insights from behavioural economics with traditional competition and market failure analysis has much scope for helping the FCA choose the best interventions. Behavioural insights have implications for many functions of the organisation: policy i.e. creating our rules and guidance; analysing firms business models, behaviour and products when authorising or supervising firms; building evidence for enforcement cases; and shaping FCA and firm communications with customers. We believe that the challenges are surmountable and this paper contributes to the foundations for the FCA to undertake wide-ranging, integrated analysis of financial markets and then act on the results.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 51

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 52

Thematic peer review on the FSB Principles for Reducing Reliance on Credit Rating Agency (CRA) Ratings

Questionnaire Introduction

In October 2010, the FSB issued Principles for Reducing Reliance on CRA Ratings. The goal of the Principles is to end mechanistic reliance on CRA ratings by banks, institutional investors and other market participants. The hard wiring of CRA ratings in regulation has been wrongly interpreted as providing those ratings with an official seal of approval and has reduced incentives for firms to develop their own capacity for credit risk assessment and due diligence. As demonstrated during the financial crisis, reliance on external ratings to the exclusion of internal credit assessments can be a cause of herding behaviour and of abrupt sell-offs of securities when they are downgraded (cliff effects). These effects can amplify procyclicality and cause systemic disruption. Following a February 2012 progress report by the FSB Secretariat, both the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors as well as the G20 Leaders, in their Los Cabos Declaration, called for faster progress by national authorities and SSBs in ending mechanistic reliance on credit ratings. In response to this call, the FSB Plenary at its meeting in Tokyo in October 2012 endorsed a roadmap1 with timelines to accelerate implementation of the FSB Principles, which were welcomed at the

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 53

November 2012 G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting.

The roadmap consists of two tracks: Work to reduce mechanistic reliance on CRA ratings through standards, laws and regulations. Reviews should cover the identification and reduction of references to CRA ratings in standards, laws and regulations. The reviews should also identify whether, even absent such references to CRA ratings, sufficient steps are being taken in standards, laws and regulations to actively place a duty or expectation on market participants that they will not mechanistically rely on CRA ratings; Work to promote and, where needed, require financial institutions to strengthen their own credit risk assessment processes as a replacement for reliance on CRA ratings, and disclose information on those processes. To this end, the FSB is undertaking a thematic peer review, whose main objective is to assist national authorities fulfil their commitments under the agreed CRA ratings roadmap. The aim of the review is to accelerate progress in reducing mechanistic reliance on CRA ratings by including by encouraging market participants to develop and implement adequate credit assessment processes. The peer review will focus on certain Principles, as highlighted in the questionnaire, that relate to regulatory and supervisory practices or the official sector more broadly. More specifically, the review will: Take stock of the extent to which references to CRA ratings in national laws and regulations have been identified, assessed and (where appropriate) removed or replaced with suitable alternative standards of creditworthiness; H ighlight good practices and lessons of experience from assessing, removing and/ or replacing references to CRA ratings in laws and regulations;

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 54

I dentify any challenges that have arisen in seeking to remove or replace references as set out in the Principles, and highlight potential solutions where these have been developed; and

Review national authorities progress and plans to encourage disclosure by financial institutions of information about their credit assessment processes and to further strengthen those capabilities. The primary source of information for the peer review will be member jurisdictions responses to this questionnaire.

The questionnaire is divided into four sections:

Section 1 covers the measures taken to reduce references to CRA ratings in laws and regulations (Principle I ); Section 2 covers the measures taken by the official sector to reduce market reliance on CRA ratings (Principle I I); Section 3 covers the detailed measures taken by the relevant official sector authorities to implement the detailed application of the Principles (Principle I I I ); Section 4 concerns general observations on the implementation of the Principles. National authorities should provide a consolidated response that covers all financial sub-sectors in their jurisdiction. Responses from Member States of the European Union should indicate where the responsibility for addressing a specific question resides with the European Commission or one of the European authorities (ESMA, EBA, or EIOPA). Respondents are encouraged to draw on their responses to prior surveys in this area where those are relevant for this questionnaire.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 55

The Peer Review Team will follow up with jurisdictions, as necessary, concerning plans indicated in this questionnaire before finalizing the peer review report.

Jurisdictions are also encouraged to provide updated information to the attention of the Peer Review Team as plans develop or experience is gained over the coming months.

1. Reducing reliance on CRA ratings in laws and regulations (Principle I)

General 1. Please describe the process that was used to assess references to CRA ratings in your laws and regulations for the financial sector: a)Did the authorities in your jurisdiction conduct a review of laws and regulations following publication of the CRA Principles in October 2010?

If yes:

b)Which supervisory or other authorities were involved in the assessment?

c)What steps, if any , were taken to coordinate the approach taken by the relevant authorities? d) Over what timeframe were the assessments conducted? e)If the assessments resulted in proposals for legislative and/ or regulatory change, which authorities were responsible for implementing the proposed changes? f ) H ow many of the proposed legislative and/ or regulatory changes have already been adopted? g ) H ow many legislative and/ or regulatory changes remain to be made and what is the timetable for their adoption?

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 56

h) H as the assessment been updated following the adoption of the FSB roadmap?

If no:

i) Please describe the plans by your jurisdiction to conduct a review of laws and regulations in line with the FSB roadmap. 2. Please describe the process that is being used to develop action plans for your jurisdiction as called for under the roadmap:

a)Which supervisory or other authorities are involved in the development of the action plan? To what extent is the private sector involved in this process?

b)What steps, if any , are being taken to coordinate the approach taken by the relevant authorities? c) What is the current status of the action plan for your jurisdiction? d)What is the timeframe, if any, for the completion and full implementation of the action plan?

References to CRA ratings in laws and regulations

For the following questions please provide separate responses for each of the following categories: Banks Insurance/ reinsurance companies Investment funds management, including: Collective investment schemes (i.e. schemes investing in transferrable securities such as mutual funds) Alternative investment schemes (e.g. hedge funds, endowments etc.)

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 57

Occupational retirement schemes

Collateral policies for central counterparties (CCPs) Securities issuance, including asset-backed securities and corporate debt Securities firms (broker-dealers) 3. Please provide details (using Annex I ) of all specific laws and regulations from which references to CRA ratings were removed or have been proposed to be removed following the assessment described in answer to Question 1. Please use Annex I to provide details of: a) The specific law/ regulation reference b) The text of the relevant law/ regulation c) The replacement text (where applicable) 4. Please provide details (using Annex I) of all laws and regulations where references to CRA ratings have been identified but were not replaced. a)Where references to CRA ratings were identified but not replaced or proposed to be replaced, what were the factors that lead to these references being retained? b)Will the decision not to replace the references be reviewed in the future? c) What factors might trigger a review?

5. Where CRA ratings are used to assess creditworthiness, have you developed alternative standards of assessment for the purpose of replacing references to CRA ratings in laws and regulations?

Where applicable, please provide these alternative definitions (using Annex I ).

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 58

6. Please describe the measures of creditworthiness that you have considered as alternatives to credit ratings.

What do you consider as the main advantages and weaknesses of each of these alternative creditworthiness measures?

2. Reducing market reliance on CRA ratings (Principle I I )

1.Please describe any roles played by regulatory authorities in your jurisdiction in reviewing credit risk assessment capabilities of market participants. 2.To what extent are the regulatory authorities directly involved in developing alternative credit risk assessment processes? 3.Please describe (using Annex I ) any supervisory processes and procedures used to check the adequacy of market participants own credit assessment processes in respect of: Banks Insurance/ reinsurance companies Investment funds management, including: Collective investment schemes (i.e. schemes investing in transferrable securities such as mutual funds) Alternative investment schemes (e.g. hedge funds, endowments, etc.) Occupational retirement schemes Collateral policies for central counterparties (CCPs) Securities issuance, including asset-backed securities and corporate debt Securities firms (broker-dealers) a) Please describe (using Annex I) any specific procedures that have been adopted to guard against upward biases in firms internal ratings.

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 59

4. What measures have authorities in your jurisdiction adopted to incentivise market participants to develop their internal risk management capabilities?

a)Please describe separately any additional measures taken since the publication of the FSB CRA Principles. b)What role is played by CRA ratings as part of internal credit risk management approaches for each of the above categories of market participants?

c)To what extent are market participants required to disclose information about their internal credit risk assessment processes?

3.Application of the basic principles to particular financial market activities (Principle I I I)

Please refer to Annex I

4. General

a)What are the main lessons to be drawn from the assessment and implementation process followed by the authorities in your jurisdiction? b)What have been the greatest obstacles to implementing the CRA Principles? c)Please describe any specific policies or measures that you believe have been particularly effective in reducing reliance on CRA ratings. d)Do you have any specific recommendations for amending the CRA Principles on the basis of your implementation experience? e)Are there any other general observations you would like to make about the CRA Principles or their implementation?

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 60

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 61

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 62

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 63

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 64

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 65

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 66

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 67

I nternational Association of Risk and Compliance Professionals (I ARCP) www.risk-compliance-association.com

P a g e | 68

Stress testing banks what have we learned?