Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Tumours: Will Aston, Timothy Briggs, Louis Solomon

Загружено:

ShuvashishSunuwar0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров24 страницыORTHOPAEDICS

Оригинальное название

Tumours

Авторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документORTHOPAEDICS

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров24 страницыTumours: Will Aston, Timothy Briggs, Louis Solomon

Загружено:

ShuvashishSunuwarORTHOPAEDICS

Авторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 24

Tumours

Will Aston, Timothy Briggs, Louis

Solomon

Tumours, tumour-like lesions & cysts

similar clinical presentation & management

evolving definitive classification of bone tumours &

some disorders move from one category to another

mimic each other

Incidence

Benign lesions: quite common

Primary malignant: rare

critical decisions on T/t: a working knowledge of all

the important conditions is necessary (i.e. its

essential to differentiate 3 conditions)

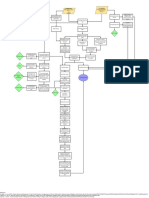

Classification of bone tumours

Based on recognition of dominant tissue in

lesions

Advantage: Knowing cell line from which

tumour has sprung may help with both

diagnosis & planning of treatment

Pitfalls in the approach of bone tumour classification:

most pervasive tissue is not necessarily the tissue

of origin

there is not necessarily any connection between

conditions in one category

there is often no relationship between benign &

malignant lesions with similar tissue elements

(e.g. osteoma and osteosarcoma)

the commonest malignant lesions in bone

metastatic tumours are not, strictly speaking,

bone tumours, i.e. not of mesenchymal origin.

Revised WHO Classification of bone tumours

Schajowicz (1994)

Predominant tissue Benign Malignant

Bone forming Osteoma, Osteoid Osteosarcoma: central,

osteoma, Osteoblastoma peripheral, parosteal

Cartilage forming Chondroma, Chondrosarcoma:

Osteochondroma, central

Chondroblastoma, peripheral

?Chondromyxoid fibroma juxtacortical

clear-cell

mesenchymal

Fibrous tissue Fibroma, Fibrosarcoma

Fibromatosis

Mixed ?Chondromyxoid fibroma

Giant-cell tumours Benign osteoclastoma Malignant osteoclastoma

Marrow tumours Ewings tumour

Myeloma

Vascular tissue Haemangioma Angiosarcoma

Haemangiopericytoma Malignant

Haemangioendothelioma haemangiopericytoma

Predominant tissue Benign Malignant

Other connective tissue Fibroma Fibrosarcoma

Fibrous histiocytoma Malignant fibrous

Lipoma histiocytoma

Liposarcoma

Other tumours Neurofibroma Adamantinoma

Neurilemmoma Chordoma

Clinical presentation of bone tumours

History

History: prolonged; delay in obtaining T/t

Asymptomatic; abnormality discovered on x-ray

i.e. incidental finding on x-ray (more likely with

benign lesions)

non-ossifying fibroma (benign): common in

children but rare > 30yrs; capable of spontaneous

resolution

Malignant tumours: silent if slow-growing &

situated in a room for inconspicuous expansion

(pelvis cavity)

History

Age

During childhood & adolescence: many benign

lesions; primary malignant tumours (Ewings

tumour & osteosarcoma)

In older people (fourth or sixth decades) :

Chondrosarcoma & fibrosarcoma

seldom seen before the sixth decade (>60yrs) :

myeloma (commonest of all primary malignant

bone tumours)

over 70 years: metastatic bone lesions are more

common than primary tumours

History

Pain

common complaint

gives little indication of nature of lesion

Progressive & unremitting pain is a sinister symptom

even a tiny lesion may be very painful if it is

encapsulated in dense bone (e.g. an osteoid osteoma)

caused by

a) rapid expansion with stretching of surrounding

tissues

b) central haemorrhage or degeneration in tumour or

c) an incipient pathological fracture

History

Swelling or appearance of a lump: alarming

patients seek advice only when a mass

becomes painful or continues to grow

(medical adviced seeked on growing or painful

mass)

History

of trauma: offered frequently;significant

whether injury initiates a pathological change

or merely draws attention to what is already

there remains unanswered

History

Neurological symptoms (paraesthesiae or

numbness)

caused by pressure upon or stretching of a

peripheral nerve

Progressive dysfunction is more ominous &

suggests invasion by an aggressive tumour

History

Pathological fracture

may be the first (and only) clinical signal

Suspicion is aroused if the injury was slight; in

elderly people, whose bones usually fracture

at the cortico-cancellous junctions, any break

in the mid-shaft should be regarded as

pathological until proved otherwise

c/fs of bone tumours

Prolonged; silent; asymptomatic & incidental finding on x-ray

Pain: pressure symptom (osteoid osteoma); central hhg /degn;

pathological #

Swelling:painful growing mass

Pathological #: with slight trauma; in elderly (at mid-shaft)

Trauma: initiate pathology or draw attention

Paresthesia & numbness: pressure symptom; progressive

dysfunction: aggressive tumour

Age: child & adolescence (bening; primary tumour like Ewing &

osteosarcome); old (40/60yr): chondrosarcoma, fibrosarcoma; (>60

yrs: myeloma); > 70 yrs: mets

4P + AST

Examination will focus on the symptomatic part

Lump:

Site (where does it arise? ): Spinal lesions (benign or

malignant) cause muscle spasm & back stiffness, or

a painful scoliosis

discrete or ill-defined (diffuse swelling with warm &

inflamed overlying skin: DD difficult to diff. tumour,

hematoma, infection)

soft or hard

pulsatile

Tender

Tumour near a jt: an effusion and/or limitation of

movement

Examination in asymptomatic part

area of lymphatic drainage (pelvis, abdomen,

chest & spine)

IMAGING

Plain x-rays

most useful of all imaging techniques

Provides informative detail can seldom be relied on

for a definitive diagnosis in which the appearances

are pathognomonic (osteochondroma, non-ossifying

fibroma, osteoid osteoma) except in some where

further investigations will be needed

Do all forms of imaging (bone scans, CT or MRI)

before undertaking a biopsy as biopsy may distort the

appearances

Location of lesion: in metaphysis or the diaphysis

solitary or multiple lesions

margins well-defined or ill-defined

Plain x-rays

Bony abnormality seen

cortical thickening

a discrete lump

ill-defined destruction

hollow cavities or radiolucent area (DD: cyst,

fibroma or chondroma)

a cyst (sharply defined boundary: benign; hazy &

diffuse boundary: invasive tumour)

Stippled calcification inside a cystic area is

characteristic of cartilage tumours

Plain x-rays

Bone surfaces suggestive of malignant change:

periosteal newbone formation &

extension of the tumour into soft tissues

Plain x-rays

soft tissues

Distorted muscle planes by swelling

Any calcification

Plain x-ray summary

Most useful in pathognomic lesions like osteochondroma,

non-ossifying fibroma, osteoid osteoma

Do all imaging before biopsy as biopsy distorts appearance

Site (D,E, M), number & border of lesion

Bony abnormality: thickened cortex, lump, hollow

radiolucent cavity (cyst, fibroma, chondroma), stippled

calcification inside cyst (cartilage tumour), cyst (sharp

border: benign; hazy border: invasive); ill-defined

destruction

Bony surface: periosteal new bone formation & extension

into soft t/s (malignancy)

Soft-tissue abnormality: distorted muscle plane,

calcification

RADIONUCLIDE SCANNING

Scanning with 99mTc-methyl diphosphonate

(99mTc-

MDP) shows non-specific reactive changes in

bone; this

can be helpful in revealing the site of a small

tumour

(e.g. an osteoid osteoma) that does not show

up clearly

on x-ray. Skeletal scintigraphy is also useful for

detecting

skip lesions or silent secondary deposits.

\

COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

CT extends the range of x-ray diagnosis; it shows

more accurately both intraosseous and extraosseous

extension of the tumour and the relationship to surrounding

structures. It may also reveal suspected

lesions in inaccessible sites, like the spine or pelvis; and

it is a reliable method of detecting pulmonary metastases.

MAGNETIC RESONANCE IMAGING

MRI provides further information. Its greatest value is

in the assessment of tumour spread: (a) within the

bone, (b) into a nearby joint and (c) into the soft tissues.

Blood vessels and the relationship of the tumour

to the perivascular space are well defined. MRI is also

useful in assessing soft-tissue tumours and cartilaginous

lesions.

Вам также может понравиться

- 08 Bone TumorsДокумент94 страницы08 Bone TumorsSara FoudaОценок пока нет

- Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology - Wills Eye Institute Oculoplastics 2 PDFДокумент303 страницыColor Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Ophthalmology - Wills Eye Institute Oculoplastics 2 PDFdinul21Оценок пока нет

- Bone Tumors and Tumorlike Conditions: Analysis With Conventional RadiographyДокумент73 страницыBone Tumors and Tumorlike Conditions: Analysis With Conventional RadiographyViskaОценок пока нет

- Radiotherapy in Penile Carcinoma: Dr. Ayush GargДокумент32 страницыRadiotherapy in Penile Carcinoma: Dr. Ayush GargMohammad Mahfujur RahmanОценок пока нет

- Oncology Oite Review 2012 120920125342 Phpapp02Документ738 страницOncology Oite Review 2012 120920125342 Phpapp02Stephen James100% (1)

- ESMO Sarcoma GIST and CUP Essentials For CliniciansДокумент91 страницаESMO Sarcoma GIST and CUP Essentials For CliniciansTonette PunjabiОценок пока нет

- Meningococcal MeningitisДокумент22 страницыMeningococcal MeningitisShuvashishSunuwar100% (1)

- Bone and Joint TumoursДокумент49 страницBone and Joint TumoursMahmoud Abu Al Amrain100% (1)

- Tumors of MusculoskeletalДокумент7 страницTumors of MusculoskeletalodiliajessicanpviaОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumor FinalДокумент156 страницBone Tumor Finalavni_stormОценок пока нет

- Benign Non-Odontogenic Tumors of Oral CavityДокумент64 страницыBenign Non-Odontogenic Tumors of Oral CavityvannaputriwОценок пока нет

- Management of Lung CancerДокумент31 страницаManagement of Lung CancerPadmaj KulkarniОценок пока нет

- Benign Bone Tumours LectureДокумент11 страницBenign Bone Tumours Lecturekyliever100% (1)

- Bone Tumours: Natasha Eleena Nor Maghfirah Hani Farhana Nur FadhilaДокумент85 страницBone Tumours: Natasha Eleena Nor Maghfirah Hani Farhana Nur FadhilaWan Nur AdilahОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumor: Daniel A. (Orthopedic Surgeon)Документ225 страницBone Tumor: Daniel A. (Orthopedic Surgeon)mebrieОценок пока нет

- Ayurveda Herbal Liver Cancer CureДокумент7 страницAyurveda Herbal Liver Cancer CureChirag Patel100% (1)

- Posttest Ans Key Intensive Onco de GuzmanДокумент2 страницыPosttest Ans Key Intensive Onco de GuzmanZymer Lee AbasoloОценок пока нет

- OSTEOSARCOMAДокумент5 страницOSTEOSARCOMALorebell75% (4)

- Benign Bone TumorsДокумент31 страницаBenign Bone TumorsDr Afsar KhanОценок пока нет

- National Cancer Control Program: IndiaДокумент29 страницNational Cancer Control Program: IndiaNitti PathakОценок пока нет

- Breast SurgeryДокумент14 страницBreast SurgeryUday Prabhu100% (1)

- An Approach To Malignant.7496050.PowerpointДокумент19 страницAn Approach To Malignant.7496050.PowerpointAndrei OlaruОценок пока нет

- Musculoskelet Al Tumors: Rizal Daulay MD, Spot. MarsДокумент98 страницMusculoskelet Al Tumors: Rizal Daulay MD, Spot. MarsMuhammad AdityaОценок пока нет

- Management of Benign Bone Neoplasm by Eyecherry 3 - 2 (Autosaved)Документ51 страницаManagement of Benign Bone Neoplasm by Eyecherry 3 - 2 (Autosaved)Osifo EmmanuelОценок пока нет

- Tumors of Musculoskeletal: Tutorial Ortopaedic SurgeryДокумент108 страницTumors of Musculoskeletal: Tutorial Ortopaedic SurgeryfarisОценок пока нет

- Neoplasma Muskuloskeletal - PRMMДокумент48 страницNeoplasma Muskuloskeletal - PRMMhello from the other sideОценок пока нет

- Tumors of Bone-2Документ33 страницыTumors of Bone-2Jackline nyawiraОценок пока нет

- Bone and Joint Neoplasm or TumorДокумент49 страницBone and Joint Neoplasm or Tumorendah rahmadaniОценок пока нет

- Tumor MusculoskeletalДокумент41 страницаTumor Musculoskeletalrisky setyanОценок пока нет

- Tumors Around Knee in PediatricsДокумент25 страницTumors Around Knee in PediatricsMike RossОценок пока нет

- Bone TumorsДокумент40 страницBone TumorsVisura PrabodОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumors - DR OkunolaДокумент36 страницBone Tumors - DR OkunolaIdris Balasa IdrisОценок пока нет

- X-Ray: Most Useful of All ImagingДокумент33 страницыX-Ray: Most Useful of All ImagingDinesh VeraОценок пока нет

- Seminar 1 OrthoДокумент139 страницSeminar 1 OrthoEng Kian NgОценок пока нет

- Slide Ajar B.2 Asdos 2015Документ111 страницSlide Ajar B.2 Asdos 2015Kumala DewiОценок пока нет

- Seminar W4 - Bone & Soft Tissue TumoursДокумент123 страницыSeminar W4 - Bone & Soft Tissue TumoursUN EPОценок пока нет

- Patologi Anatomi Kelainan MuskuloskeletalДокумент38 страницPatologi Anatomi Kelainan Muskuloskeletalmuthia saniОценок пока нет

- YeeerДокумент91 страницаYeeerbilljohn.bueno.crsОценок пока нет

- Presenbone Tumors Irfantation1Документ65 страницPresenbone Tumors Irfantation1Ya Sayyadi BilalОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumours: Mohamad Bayu SahadewaДокумент31 страницаBone Tumours: Mohamad Bayu SahadewaDwi SarwindaОценок пока нет

- Booooooone Tumors REFERATДокумент47 страницBooooooone Tumors REFERATNurlaila IshaqОценок пока нет

- Soft Tissue Tumor SeminarДокумент39 страницSoft Tissue Tumor SeminarAhmad SyahmiОценок пока нет

- jnu bone tumors - 複本Документ130 страницjnu bone tumors - 複本Wai Kwong ChiuОценок пока нет

- 3 - Imaging Hand Tumours FESSHДокумент37 страниц3 - Imaging Hand Tumours FESSHProfesseur Christian DumontierОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumor DefinitionДокумент2 страницыBone Tumor DefinitionJinsen Paul MartinОценок пока нет

- Referat Primery Bone TumorsДокумент62 страницыReferat Primery Bone Tumorsrahma nilasari100% (1)

- Pendekatan Diagnostik Tumor MSKДокумент73 страницыPendekatan Diagnostik Tumor MSKAulia AlmiraОценок пока нет

- Short Version Malignant Bone LesionsДокумент57 страницShort Version Malignant Bone LesionsAfОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis of Bone Tumours: 1. Age of Patient 2. Location of Tumour 3. Radiological Appearance 4. Histological FeaturesДокумент69 страницDiagnosis of Bone Tumours: 1. Age of Patient 2. Location of Tumour 3. Radiological Appearance 4. Histological Featuresyurie_ameliaОценок пока нет

- Benign Bone TumoursДокумент13 страницBenign Bone TumoursAnisah MahmudahОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumor: A. Nithya 1 Year M.SC (Nursing)Документ46 страницBone Tumor: A. Nithya 1 Year M.SC (Nursing)nithya nithyaОценок пока нет

- Neoplasms of The Musculoskeletal TissuesДокумент21 страницаNeoplasms of The Musculoskeletal Tissuesi dewa wisnu putraОценок пока нет

- Orthopedic Tumors and OsteoarthritisДокумент6 страницOrthopedic Tumors and OsteoarthritisSai Snigdha MohantyОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumors and Tumor-Like LesionsДокумент22 страницыBone Tumors and Tumor-Like LesionsOswin Caicedo100% (1)

- Osteochondroma of Distal FemurДокумент37 страницOsteochondroma of Distal FemurafinaОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumours: - Jeffrey Pradeep RajДокумент42 страницыBone Tumours: - Jeffrey Pradeep RajjeffreyprajОценок пока нет

- Bone Pathology LectureДокумент114 страницBone Pathology LecturemikulcicaОценок пока нет

- Anatomy of The Upper and Lower Extremities Neoplasms of MusculosДокумент93 страницыAnatomy of The Upper and Lower Extremities Neoplasms of MusculosraihanekapОценок пока нет

- Imaging Evaluation of Malignant Chest Wall NeoplasmsДокумент51 страницаImaging Evaluation of Malignant Chest Wall NeoplasmsRicky SeptafiantyОценок пока нет

- Septic ArthritisДокумент94 страницыSeptic ArthritisCut Riska NovizaОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumors 1Документ44 страницыBone Tumors 1George josephОценок пока нет

- Bone Tumor: Kemas M Dahlan Fahriza UtamaДокумент65 страницBone Tumor: Kemas M Dahlan Fahriza UtamaAyu Ersya WindiraОценок пока нет

- MS TumorsДокумент16 страницMS TumorsASM MutahirОценок пока нет

- Malignant Tumors of BoneДокумент29 страницMalignant Tumors of Bonenuthu mahnОценок пока нет

- Dr. Andre Sihombing. SpotДокумент56 страницDr. Andre Sihombing. SpotDinda AdiaОценок пока нет

- A Simple Guide to Fibro-sarcoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsОт EverandA Simple Guide to Fibro-sarcoma, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsОценок пока нет

- Soft Tissue Tumors: A Practical and Comprehensive Guide to Sarcomas and Benign NeoplasmsОт EverandSoft Tissue Tumors: A Practical and Comprehensive Guide to Sarcomas and Benign NeoplasmsОценок пока нет

- Crystal Deposition DisordersДокумент4 страницыCrystal Deposition DisordersShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Inhalational Agents: General PrinciplesДокумент13 страницInhalational Agents: General PrinciplesShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- General AppearanceДокумент2 страницыGeneral AppearanceShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1Документ12 страницSexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1Документ9 страницSexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Ectatic ConditionsДокумент11 страницEctatic ConditionsShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Sexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1Документ9 страницSexually Transmitted Infections (Stis) : 4Th October, 2015 1ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Corrosives 1Документ13 страницCorrosives 1ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- 1Документ12 страниц1ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Forensic MedicineДокумент31 страницаForensic MedicineShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Obstetric InstrumentsДокумент15 страницObstetric InstrumentsShuvashishSunuwar100% (1)

- Oral Cavity: Anatomy GI SystemДокумент5 страницOral Cavity: Anatomy GI SystemShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Chemical and Pill EsophagitisДокумент3 страницыChemical and Pill EsophagitisShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Seborrhoeic Dermatitis: Synonyms - Pityrosporal Dermatitis - Dermatitis of The Sebaceous AreasДокумент3 страницыSeborrhoeic Dermatitis: Synonyms - Pityrosporal Dermatitis - Dermatitis of The Sebaceous AreasShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- Chi Kun GunyaДокумент20 страницChi Kun GunyaShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- HHV3Документ6 страницHHV3ShuvashishSunuwarОценок пока нет

- 10 Anos Cross Trial Jco2021Документ11 страниц10 Anos Cross Trial Jco2021alomeletyОценок пока нет

- Clinico-Histopathological Analysis of Orbito-Ocular Lesions: A Hospital-Based StudyДокумент6 страницClinico-Histopathological Analysis of Orbito-Ocular Lesions: A Hospital-Based StudyFKUMP17 Part 2Оценок пока нет

- Hornick Carcinoma of Unknown Primary 8 June 1400Документ87 страницHornick Carcinoma of Unknown Primary 8 June 1400Olteanu Dragos-NicolaeОценок пока нет

- FNA Biopsy Thyroid Nodules BrochureДокумент2 страницыFNA Biopsy Thyroid Nodules BrochureAndreeaBraduОценок пока нет

- Consensus Statement: The 16th Annual Western Canadian Gastrointestinal Cancer Consensus Conference Saskatoon, Saskatchewan September 5-6, 2014Документ12 страницConsensus Statement: The 16th Annual Western Canadian Gastrointestinal Cancer Consensus Conference Saskatoon, Saskatchewan September 5-6, 2014Amina GoharyОценок пока нет

- Project CancerДокумент4 страницыProject CancerShinu BathamОценок пока нет

- 2023 SABCS Abstract ReportДокумент3 742 страницы2023 SABCS Abstract ReportNeetumishti ChadhaОценок пока нет

- TIRADS ClassificationДокумент1 страницаTIRADS ClassificationkristwibowoОценок пока нет

- All Program 240423Документ26 страницAll Program 240423NoneОценок пока нет

- (SURG) Case Surgical Oncology PDFДокумент5 страниц(SURG) Case Surgical Oncology PDFDave RapaconОценок пока нет

- College of Nursing Silliman University Dumaguete City: Mrs. Corazon Ordonez, BSN-RNДокумент23 страницыCollege of Nursing Silliman University Dumaguete City: Mrs. Corazon Ordonez, BSN-RNMarodvi ZernaОценок пока нет

- Cutaneous MelanomaДокумент199 страницCutaneous MelanomahapzanimОценок пока нет

- ASCO Bladder Cancer Talk Jun 2013 v2Документ37 страницASCO Bladder Cancer Talk Jun 2013 v2Prof_Nick_JamesОценок пока нет

- BreastQ-bank Full - 2Документ44 страницыBreastQ-bank Full - 2Helene AlawamiОценок пока нет

- Modern Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Ppt-1Документ25 страницModern Biomarkers in Prostate Cancer Ppt-1FredОценок пока нет

- Entrectinib - MoA and ROS1-NTRK Data PackageДокумент126 страницEntrectinib - MoA and ROS1-NTRK Data PackageDavid LeeОценок пока нет

- Radiofrequency Ablation and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy For Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Should They Clash or Reconcile?Документ24 страницыRadiofrequency Ablation and Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy For Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Should They Clash or Reconcile?Amina GoharyОценок пока нет

- Kaposi-Sarcoma PathophysiologyДокумент1 страницаKaposi-Sarcoma PathophysiologyChiara FajardoОценок пока нет

- IMP Society DetailsДокумент16 страницIMP Society DetailsRohan KulkarniОценок пока нет

- Lung Cancer Oncologic NursingДокумент39 страницLung Cancer Oncologic NursingLoren PanОценок пока нет

- Colon and Rectum Colorectal CancerДокумент20 страницColon and Rectum Colorectal CancerJemima Nove JapitanaОценок пока нет