Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Utilitarianism (STUART)

Загружено:

yuta nakamoto0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров19 страницАвторское право

© © All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

0 оценок0% нашли этот документ полезным (0 голосов)

13 просмотров19 страницUtilitarianism (STUART)

Загружено:

yuta nakamotoАвторское право:

© All Rights Reserved

Доступные форматы

Скачайте в формате PPTX, PDF, TXT или читайте онлайн в Scribd

Вы находитесь на странице: 1из 19

Utilitarianism

By:Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart

Prepared by: Group 5

John Stuart Mill: Ethics

The ethical theory of John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) is most

extensively articulated in his classical

text Utilitarianism (1861). Its goal is to justify the utilitarian

principle as the foundation of morals. This principle says

actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote overall

human happiness. So, Mill focuses on consequences of actions

and not on rights nor ethical sentiments.

This article primarily examines the central ideas of his

text Utilitarianism, but the article's last two sections are

devoted to Mill's views on the freedom of the will and the

justification of punishment, which are found in System of

Logic (1843) and Examination of Sir William Hamilton’s

Philosophy (1865), respectively.

Introductory Remarks

Mill tells us in his Autobiography that the “little work with

the name” Utilitarianism arose from unpublished material, the

greater part of which he completed in the final years of his

marriage to Harriet Taylor, that is, before 1858. For its

publication he brought old manuscripts into form and added

some new material.

The work first appeared in 1861 as a series of three articles

for Fraser’s Magazine, a journal that, though directed at an

educated audience, was by no means a philosophical organ.

Mill planned from the beginning a separate book publication,

which came to light in 1863. Even if the circumstances of the

genesis of this work gesture to an occasional piece with a

popular goal, on closer examination Utilitarianism turns out to

be a carefully conceived work, rich in thought.

One must not forget that since his first reading of Bentham

in the winter of 1821-22, the time to which Mill dates his

conversion to utilitarianism, forty years had passed. Taken

this way, Utilitarianism was anything but a philosophical

accessory, and instead the programmatic text of a thinker

who for decades had understood himself as a utilitarian and

who was profoundly familiar with popular objections to the

principle of utility in moral theory. Almost ten years earlier

(1852) Mill had defended utilitarianism against the

intuitionistic philosopher William Whewell (Whewell on

Moral Philosophy).

Mill’s Theory of Value and the Principle of Utility

Mill defines "utilitarianism" as the creed that considers a

particular “theory of life” as the “foundation of morals” (CW 10,

210). His view of theory of life was monistic: There is one thing,

and one thing only, that is intrinsically desirable, namely

pleasure. In contrast to a form of hedonism that conceives

pleasure as a homogeneous matter, Mill was convinced that

some types of pleasure are more valuable than others in virtue

of their inherent qualities. For this reason, his position is often

called “qualitative hedonism”. Many philosophers hold that

qualitative hedonism is no consistent position. Hedonism

asserts that pleasure is the only intrinsic value. Under this

assumption, the critics argue, there can be no evaluative basis

for the distinction between higher and lower pleasures.

Probably the first ones to raise this common objection were the

British idealists F. H. Bradley (1876/1988) and T. H. Green

(1883/2003).

Morality as a System of Social Rules

The fifth and final chapter of Utilitarianism is of unusual

importance for Mill’s theory of moral obligation. Until the

1970s, the significance of the chapter had been largely

overlooked. It then became one of the bridgeheads of a

revisionist interpretation of Mill, which is associated with the

work of David Lyons, John Skorupski and others.

Mill worked very hard to hammer the fifth chapter into shape

and his success has great meaning for him. Towards the end of

the book he maintains the “considerations which have now

been adduced resolve, I conceive, the only real difficulty in the

utilitarian theory of morals.” (CW 10, 259)

The Role of Moral Rules (Secondary Principles)

In Utilitarianism, Mill designs the following model of moral

deliberation. In the first step the actor should examine which of

the rules (secondary principles) in the moral code of his or her

society are pertinent in the given situation. If in a given

situation moral rules (secondary principles) conflict, then (and

only then) can the second step invoke the formula of utility (CW

10, 226) as a first principle. Pointedly one could say: the

principle of utility is for Mill not a component of morality, but

instead its basis. It serves the validation of rightness for our

moral system and allows – as a meta-rule – the decision of

conflicting norms. In the introductory chapter

of Utilitarianism, Mill maintains that it would be “easy to show

that whatever steadiness or consistency these moral beliefs

have attained, has been mainly due to the tacit influence of a

standard not recognized” (CW 10, 207), namely the principle of

utility.

The tacit influence of the principle of utility made sure that a

considerable part of the moral code of our society is justified

(promotes general well-being). But other parts are clearly

unjustified. One case that worried Mill deeply was the role of

women in Victorian Britain. In “The Subjection of Women”

(1869) he criticizesthe “legal subordination of one sex to the

other” (CW 21, 261) as incompatible with “all the principles

involved in modern society” (CW 21, 280).

Rule or Act Utilitarianism?

There is considerable disagreement as to whether Mill should

be read as a rule utilitarian or an (indirect) act utilitarian. Many

philosophers look upon rule utilitarianism as an untenable

position and favor an act utilitarian reading of Mill (Crisp

1997). Under the pressure of many contradicting passages,

however, a straightforward act utilitarian interpretation is

difficult to sustain. Recent studies emphasize Mill’s rule

utilitarian leanings (Miller 2010, 2011) or find elements of both

theories in Mill (West 2004).

In Utilitarianism he seems to give two different formulations of

the utilitarian standard. The first points in an act utilitarian, the

second in a rule utilitarian direction.

Since act and rule utilitarianism are incompatible claims

about what makes actions morally right, the formulations

open up the fundamental question concerning what style of

utilitarianism Mill wants to advocate and whether his moral

theory forms a consistent whole. It is important to note that

the distinction between rule and act utilitarianism had not

yet been introduced in Mill’s days. Thus Mill is not to blame

for failing to make explicit which of the two approaches he

advocates.

Applying the Standard of Morality

In “Whewell on Moral Philosophy” (1852), Mill rejects an

objection raised by one of his most competent philosophical

adversaries. Whewell claimed that utilitarianism permits

murder and other crimes in particular circumstances and is

therefore incompatible with our considered moral judgments.

Mill’s discussion of Whewell’s criticism is exceedingly helpful in

clarifying his ethical approach:

Take, for example, the case of murder. There are many

persons to kill whom would be to remove men who are a

cause of no good to any human being, of cruel physical and

moral suffering to several, and whose whole influence tends

to increase the mass of unhappiness and vice. Were such a

man to be assassinated, the balance of traceable

consequences would be greatly in favour of the act. (CW 10,

181)

The Meaning of the First Formula

What has been said about Mill’s conception of morality as a

system of social rules is relevant for the interpretation of

Mill’s First Formula of utilitarianism. The Formula says that

actions are right “in proportion as they tend to promote

happiness” and wrong “as they tend to produce the reverse of

happiness” (CW 10, 210). Roughly said, actions are right insofar

as they facilitate happiness, and wrong insofar as they result in

suffering. Mill does not write “morally right” or “morally

wrong”, but simply “right” and “wrong”. This is important. Mill

emphasizes in many places that virtuous actions can exhibit a

negative balance of happiness in a singular case. If the word

“moral” occurred in the First Formula, then the noted virtuous

actions would be, for Mill, morally wrong. But as we have seen,

this is not his view. Virtuous actions are morally right, even if

they are objectively wrong under particular circumstances.

Right in Proportion and Tendencies

For contemporary readers it is striking that Mill’s First

Formula does not explicitly relate to maximization. Mill does

not write, as one might expect, that only the action which leads

to the best consequences is right. In other places in the text we

hear of the “promotion” or “multiplication” of happiness, and

not of the “maximization”. Alone does the “Greatest Happiness

Principle” explicitly refer to maximization. The actual formula,

in contrast, has to do with gradual differences (right in

proportion). Actions which add to the sum of happiness in the

world but fail to maximize happiness thus can be right, even if

to a lesser degree.

Right in Proportion and Tendencies

For contemporary readers it is striking that Mill’s First

Formula does not explicitly relate to maximization. Mill does

not write, as one might expect, that only the action which leads

to the best consequences is right. In other places in the text we

hear of the “promotion” or “multiplication” of happiness, and

not of the “maximization”. Alone does the “Greatest Happiness

Principle” explicitly refer to maximization. The actual formula,

in contrast, has to do with gradual differences (right in

proportion). Actions which add to the sum of happiness in the

world but fail to maximize happiness thus can be right, even if

to a lesser degree.

Utility and Justice

In the final chapter of Utilitarianism, Mill turns to the

sentiment of justice. Actions that are perceived as unjust

provoke outrage. The spontaneity of this feeling and its

intensity makes it impossible for it to be ignored by the theory

of morals. Mill considers two possible interpretations of the

source of the sentiment of justice: first of all, that we are

equipped with a sense of justice which is an independent source

of moral judgment; second, that there is a general and

independent principle of justice. Both interpretations are

irreconcilable with Mill’s position, and thus it is no wonder that

he takes this issue to be of exceptional importance. He names

the integration of justice the only real difficulty for utilitarian

theory (CW 10, 259).

The Proof of Utilitarianism

What Mill names the “proof” of utilitarianism belongs

presumably to the most frequently attacked text passages in the

history of philosophy. Geoffrey Sayre-McCord once remarked

that Mill seems to answer by example the question of how many

serious mistakes a brilliant philosopher can make within a brief

paragraph (Sayre-McCord 2001, 330). Meanwhile the

secondary literature has made it clear that Mill’s proof contains

no logical fallacies and is less foolish than often portrayed.

Evaluating Consequences

According to Mill’s Second Formula of the utilitarian

standard, a good human life must be rich in enjoyments, in

both quantitative and qualitative respects. A manner of

existence without access to the higher pleasures is not

desirable: “It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a

pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool

satisfied.” (CW 10, 212).

Freedom of Will

In various places of his work John Stuart Mill occupied

himself with the question of the freedom of the human will. The

respective chapter in the System ofLogic he later claimed was

the best part of the entire book. Here Mill presents the solution

to a problem with which he wrestled not only intellectually. In

his Autobiography he calls it a “heavy burden” and reports: “I

pondered painfully on the subject.” (CW 1, 177)

Responsibility and Punishment

Mill variously examines the thesis that punishment is only

justified if the perpetrator could have acted differently. A

contemporary of Mill’s, the social reformer Robert Owen,

claimed that punishment of the breaking of social norms is

unjustified, because the character of a person is the result of

social influences. No one is the author of himself. Because

actions follow from the character and one is not responsible for

this, it is not just to punish people for the violation of norm

which they could not help violating. It was not within their

power to act differently. And it is unjust to punish someone for

something, if he could not do anything to hinder its occurrence

(CW 9, 453).

Вам также может понравиться

- John Stuart MillДокумент21 страницаJohn Stuart MillBayram J. Gascot HernándezОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill PDFДокумент21 страницаJohn Stuart Mill PDFBayram J. Gascot HernándezОценок пока нет

- Mill's Utilitarianism and LiberalismДокумент8 страницMill's Utilitarianism and LiberalismPranjal SharmaОценок пока нет

- UtilitarianismДокумент17 страницUtilitarianismThea Luz Margarette RomarezОценок пока нет

- Jonh Stuart MillДокумент7 страницJonh Stuart Millmayank kumarОценок пока нет

- Utilitarianism (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)От EverandUtilitarianism (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Рейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (277)

- Utilitarianism NotesДокумент5 страницUtilitarianism NotesLorenzo CamachoОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill'S Education and "Enlargement"Документ11 страницJohn Stuart Mill'S Education and "Enlargement"Apple Pearl A. ValeraОценок пока нет

- Utilitarianism by John Stuart MillДокумент31 страницаUtilitarianism by John Stuart MillChristine Carpio-aldeguerОценок пока нет

- JS Mill, UtilitarianismДокумент2 страницыJS Mill, UtilitarianismManjare Hassin RaadОценок пока нет

- Phil 167Документ12 страницPhil 167mirasultonesОценок пока нет

- Utilitarianism (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)От EverandUtilitarianism (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Рейтинг: 3.5 из 5 звезд3.5/5 (277)

- Williams' Integrity: Is The Utilitarian's Calculus Too Inhuman For Morality?Документ18 страницWilliams' Integrity: Is The Utilitarian's Calculus Too Inhuman For Morality?Su San LieОценок пока нет

- UtilitarianismДокумент6 страницUtilitarianismRon Joshua ImperialОценок пока нет

- Political Philosophy: A Practical Guide to the Select Works of John Stuart MillОт EverandPolitical Philosophy: A Practical Guide to the Select Works of John Stuart MillОценок пока нет

- J.S Mill UtilitarianismДокумент13 страницJ.S Mill Utilitarianismnandini negiОценок пока нет

- The Philosophy of Swine by CCДокумент7 страницThe Philosophy of Swine by CCCindy ChengОценок пока нет

- PDF Mill Summary GradesaverДокумент12 страницPDF Mill Summary GradesaverChen Briones100% (1)

- Women's Rights: UtilitarianismДокумент4 страницыWomen's Rights: UtilitarianismSalahudin el EjubiОценок пока нет

- UtilitarianismДокумент14 страницUtilitarianismRoopanki KalraОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill's On Liberty - John SkorupskiДокумент4 страницыJohn Stuart Mill's On Liberty - John SkorupskiAlbert AdrianОценок пока нет

- Ethics 7Документ8 страницEthics 7Agarwal PhotosОценок пока нет

- J.S. Mill - UtilitarianismДокумент5 страницJ.S. Mill - UtilitarianismSamia AgarwalОценок пока нет

- Literature Review On UtilitarianismДокумент4 страницыLiterature Review On Utilitarianismafmzaoahmicfxg100% (1)

- JKDDela Cruz - Assignment 1 - Module2 - 12.7.2021Документ5 страницJKDDela Cruz - Assignment 1 - Module2 - 12.7.2021jericho karlo dela cruzОценок пока нет

- Poplution TheoryДокумент8 страницPoplution TheoryZahra' HamidОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill Book ReviewДокумент4 страницыJohn Stuart Mill Book Reviewben hamerОценок пока нет

- Mill Utilitarianism ThesisДокумент5 страницMill Utilitarianism Thesislbbzfoxff100% (2)

- Eva Rojiatul AfwaДокумент10 страницEva Rojiatul AfwaDr. AmirudinОценок пока нет

- Ethics Module 2Документ15 страницEthics Module 2Miralyn RuelОценок пока нет

- The Subjection of Women (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)От EverandThe Subjection of Women (Barnes & Noble Library of Essential Reading)Оценок пока нет

- Engleska Viktorijanska KnjizevnostДокумент29 страницEngleska Viktorijanska KnjizevnostEdin BešlićОценок пока нет

- Self-Interest and Social Order in Classical Liberalism: The Essays of George H. SmithОт EverandSelf-Interest and Social Order in Classical Liberalism: The Essays of George H. SmithОценок пока нет

- Chapter 2 UtilitarianismДокумент14 страницChapter 2 UtilitarianismMabie ToddОценок пока нет

- UtilitarianismДокумент4 страницыUtilitarianismAnish MallОценок пока нет

- Utilitarianism Is An Ethical Theory That Argues For The Goodness of Pleasure andДокумент3 страницыUtilitarianism Is An Ethical Theory That Argues For The Goodness of Pleasure andCJ IbaleОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill ThesisДокумент5 страницJohn Stuart Mill ThesisAaron Anyaakuu100% (2)

- Student Model Answer 25 MarkerДокумент4 страницыStudent Model Answer 25 MarkerMary OdeleyeОценок пока нет

- Essay On (Negative) FreedomДокумент7 страницEssay On (Negative) Freedoms0191162Оценок пока нет

- Altruism and VolunteerismДокумент29 страницAltruism and VolunteerismAna MurarescuОценок пока нет

- If There Is Anyone Who Is Liberal It Is John Stuart MillДокумент5 страницIf There Is Anyone Who Is Liberal It Is John Stuart MillAzure KenОценок пока нет

- From Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities: An Evolutionary Economics without Homo economicusОт EverandFrom Pleasure Machines to Moral Communities: An Evolutionary Economics without Homo economicusОценок пока нет

- Bio Act Rule NoteДокумент3 страницыBio Act Rule NotePsyZeroОценок пока нет

- John Stuart Mill: Major Works: A System of Logic (1843), Principles of Political Economy (1848), "OnДокумент5 страницJohn Stuart Mill: Major Works: A System of Logic (1843), Principles of Political Economy (1848), "OnBently JohnsonОценок пока нет

- Adam's Smith Concept of Social Justice Braham University of HamburgДокумент27 страницAdam's Smith Concept of Social Justice Braham University of Hamburgb2707100Оценок пока нет

- Long Questions JS MILLДокумент5 страницLong Questions JS MILLSajid CheemaОценок пока нет

- Classical UtilitarianismДокумент24 страницыClassical UtilitarianismCielo Dela CruzОценок пока нет

- Iwona Janicka - Review of Stimilli, The Debt of The LivingДокумент4 страницыIwona Janicka - Review of Stimilli, The Debt of The LivingGerman CanoОценок пока нет

- SociologyДокумент29 страницSociologyBry EsguerraОценок пока нет

- POL320 Mill NotesДокумент3 страницыPOL320 Mill NotesAnonymous clKLzUОценок пока нет

- John Stuart MillДокумент6 страницJohn Stuart MillSagheera ZaibОценок пока нет

- The Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillДокумент17 страницThe Libertarian Philosophy of John Stuart MillPetar MitrovicОценок пока нет

- The British Utilitarians: John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)Документ4 страницыThe British Utilitarians: John Stuart Mill (1806-1873)Ivy Mhae SantiaguelОценок пока нет

- Hilosopher Faceoff: Rousseau vs. Mill: "On Liberty"Документ8 страницHilosopher Faceoff: Rousseau vs. Mill: "On Liberty"jibranqqОценок пока нет

- UtilitarianismДокумент3 страницыUtilitarianismMireya BugejaОценок пока нет

- Jonah A, Omane O, Kumah A, Afriyie P, Owusu A - 2015 - The Perception of Accounting Literacy On Profitability of Small and Medium EnterpriseДокумент58 страницJonah A, Omane O, Kumah A, Afriyie P, Owusu A - 2015 - The Perception of Accounting Literacy On Profitability of Small and Medium Enterpriseyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- An Evaluation of Accounting Information System and Performance of Small Scale Enterprises in Kwara State, NigeriaДокумент16 страницAn Evaluation of Accounting Information System and Performance of Small Scale Enterprises in Kwara State, Nigeriayuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Immanuel Kant: - German PhilosopherДокумент11 страницImmanuel Kant: - German Philosopheryuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Classical Philosophies and Their Implications On BusinessДокумент11 страницClassical Philosophies and Their Implications On Businessyuta nakamoto33% (3)

- Plato: The Philosopher KingДокумент14 страницPlato: The Philosopher Kingyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Kirumbi S - 2019 - The Impact of Financial Literacy On The Performance of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Morogoro MunicipalДокумент101 страницаKirumbi S - 2019 - The Impact of Financial Literacy On The Performance of Small and Medium Scale Enterprises in Morogoro Municipalyuta nakamoto100% (1)

- Socrates: Socratic Method and Entrepreneurial LearningДокумент7 страницSocrates: Socratic Method and Entrepreneurial Learningyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Umogbaimonica, Agwa, Asenge - 2018 - Financial Literacy and Performance of Small and MEdium Scale Enterprises in Benue State, NigeriaДокумент15 страницUmogbaimonica, Agwa, Asenge - 2018 - Financial Literacy and Performance of Small and MEdium Scale Enterprises in Benue State, Nigeriayuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation Vol.1, No.1, pp.15-26, 2018Документ12 страницInternational Journal of Entrepreneurship and Business Innovation Vol.1, No.1, pp.15-26, 2018yuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Thabet O, Ali A, Kantakji M - 2019 - Financial Literacy Among SME's in Malaysia 565774Документ8 страницThabet O, Ali A, Kantakji M - 2019 - Financial Literacy Among SME's in Malaysia 565774yuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Menike LMCS - 2018 - Effect of Financial Literacy On Firm Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in Sri LankaДокумент25 страницMenike LMCS - 2018 - Effect of Financial Literacy On Firm Performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in Sri Lankayuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Jemal L - 2019 - Effect of Financial Literacy On Financial Performance of Medium Scale Enterprise - Case Study in Hwassa City, EthiopiaДокумент7 страницJemal L - 2019 - Effect of Financial Literacy On Financial Performance of Medium Scale Enterprise - Case Study in Hwassa City, Ethiopiayuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

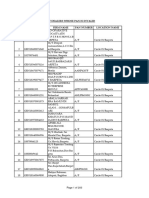

- Emp - I D Lastname Firstnam E M I Gender Age Address Yrsinservic E PositionДокумент2 страницыEmp - I D Lastname Firstnam E M I Gender Age Address Yrsinservic E Positionyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Thematic Evaluation: Adb Support For SmesДокумент47 страницThematic Evaluation: Adb Support For Smesyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- B1439026 - 2018 - The Impact of Financial Literacy On Performance of Small To Medium Enterprise - Survey of SMES in Bindura UrbanДокумент81 страницаB1439026 - 2018 - The Impact of Financial Literacy On Performance of Small To Medium Enterprise - Survey of SMES in Bindura Urbanyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Tuffour J - 2020 - Assessing The Effect of Financial Literacy Amon Managers On The Performance of Small-Scale EnterprisesДокумент19 страницTuffour J - 2020 - Assessing The Effect of Financial Literacy Amon Managers On The Performance of Small-Scale Enterprisesyuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- Agyapong D, Attram A - 2019 - The Effect of Owner-Manager's Financial Literacy On The Performance of SMEs in The Cape Coast Metropolis in GhanaДокумент13 страницAgyapong D, Attram A - 2019 - The Effect of Owner-Manager's Financial Literacy On The Performance of SMEs in The Cape Coast Metropolis in Ghanayuta nakamotoОценок пока нет

- SivamayamДокумент2 страницыSivamayamsmsekarОценок пока нет

- What Is Spirituality ? (Authored by Shriram Sharma Acharya)Документ118 страницWhat Is Spirituality ? (Authored by Shriram Sharma Acharya)Guiding Thoughts- Books by Pandit Shriram Sharma Acharya100% (3)

- Pan InvalidДокумент203 страницыPan Invalidlovelyraajiraajeetha1999Оценок пока нет

- Exercise Bahasa Inggris Kelas B 6 April 2021Документ52 страницыExercise Bahasa Inggris Kelas B 6 April 2021Siti Munawarotun NadhivahОценок пока нет

- Departure of The SoulДокумент64 страницыDeparture of The SoulVivian Kark100% (10)

- Doing TheologyДокумент4 страницыDoing TheologyCleve Andre EroОценок пока нет

- Franz Kafka BiographyДокумент10 страницFranz Kafka BiographyFaith CalisuraОценок пока нет

- Skanda Sashti KavachamДокумент19 страницSkanda Sashti Kavachamravi_naОценок пока нет

- Presentation 1Документ9 страницPresentation 1Jcka AcaОценок пока нет

- Piety and Identity Sacred Travel in The Classical WorldДокумент10 страницPiety and Identity Sacred Travel in The Classical Worldcksgnl1203Оценок пока нет

- Diogenes: Order The Status of Woman in Ancient India: Compulsives of The PatriarchalДокумент15 страницDiogenes: Order The Status of Woman in Ancient India: Compulsives of The PatriarchalSuvasreeKaranjaiОценок пока нет

- Sankardeva and His Theatrical Innovations: Implications Towards A New Social ConsciousnessДокумент5 страницSankardeva and His Theatrical Innovations: Implications Towards A New Social ConsciousnessSaurav SenguptaОценок пока нет

- The Globalization of ReligionДокумент21 страницаThe Globalization of ReligionJalen VinsonОценок пока нет

- D20 - 3.5 - Spelljammer - Shadow of The Spider MoonДокумент49 страницD20 - 3.5 - Spelljammer - Shadow of The Spider MoonWilliam Hughes100% (3)

- Paul's QualificationДокумент10 страницPaul's QualificationKiran DОценок пока нет

- 07-05-14 EditionДокумент28 страниц07-05-14 EditionSan Mateo Daily JournalОценок пока нет

- Ancient Cosmological Symbolism in The Initial Canberra Plan Peter R. ProudfootДокумент31 страницаAncient Cosmological Symbolism in The Initial Canberra Plan Peter R. ProudfootAdriano Piantella100% (1)

- UntitledДокумент377 страницUntitledapi-248722996100% (1)

- Dantalion Jones The Forbidden Book of Getting What You Want OCR AFRДокумент148 страницDantalion Jones The Forbidden Book of Getting What You Want OCR AFRKanes Bell100% (1)

- Dus Mahavidya Shabar Mantra Sadhana (दस महाविद्या शाबर मंत्र साधना एवं सिद्धि)Документ23 страницыDus Mahavidya Shabar Mantra Sadhana (दस महाविद्या शाबर मंत्र साधना एवं सिद्धि)Gurudev Shri Raj Verma ji90% (10)

- YazidiДокумент21 страницаYazidiStephan Wozniak100% (1)

- 26.02.2019 East Wharf BulkДокумент4 страницы26.02.2019 East Wharf BulkWajahat HasnainОценок пока нет

- ISB 542 Introduction To Fiqh Muamalat: The Concept of Property (Al-Maal) in IslamДокумент22 страницыISB 542 Introduction To Fiqh Muamalat: The Concept of Property (Al-Maal) in IslamsophiaОценок пока нет

- Eight Verses of The Yorozuyo - Tenrikyo Resource WikiДокумент4 страницыEight Verses of The Yorozuyo - Tenrikyo Resource Wikiluis.fariasОценок пока нет

- Bing Chap5Документ5 страницBing Chap5Aisya Az ZahraОценок пока нет

- Module Islam - Grade 8Документ6 страницModule Islam - Grade 8Mikael Cabanalan FerrerОценок пока нет

- AJAPA Japa MeditationДокумент15 страницAJAPA Japa Meditationvin DVCОценок пока нет

- A Guide To Color Symbolism Jill MortonДокумент79 страницA Guide To Color Symbolism Jill Mortonhysleken100% (1)

- OPPT Definitions PDFДокумент2 страницыOPPT Definitions PDFAimee HallОценок пока нет

- A Rare Engraving by Gerard Audran - Battle of The Milvian Bridge - ToadДокумент2 страницыA Rare Engraving by Gerard Audran - Battle of The Milvian Bridge - ToadRadu Bogdan StoicaОценок пока нет