Академический Документы

Профессиональный Документы

Культура Документы

Am. J. Epidemiol.-2004-Lee-636-41

Загружено:

Robert DwitamaАвторское право

Доступные форматы

Поделиться этим документом

Поделиться или встроить документ

Этот документ был вам полезен?

Это неприемлемый материал?

Пожаловаться на этот документАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

Am. J. Epidemiol.-2004-Lee-636-41

Загружено:

Robert DwitamaАвторское право:

Доступные форматы

American Journal of Epidemiology

Copyright 2004 by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

All rights reserved

Vol. 160, No. 7

Printed in U.S.A.

DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwh274

The Weekend Warrior and Risk of Mortality

I-Min Lee1,2, Howard D. Sesso1,2, Yuko Oguma1,3, and Ralph S. Paffenbarger, Jr.1,4

1

Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Division of Preventive Medicine, Brigham and Womens Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

3 Sports Medicine Research Center, Keio University, Yokohama, Japan.

4 Division of Epidemiology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA.

2

Received for publication January 27, 2004; accepted for publication May 4, 2004.

exercise; mortality; motor activity; physical fitness

Abbreviations: ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CI, confidence

interval.

There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity

under heaven.

Ecclesiastes 3:1

These words of King Solomon, written around 940 BC,

may have garnered widespread support then, but the average

person living in a developed country today is likely to

disagree. For example, by some estimates, the average time

spent at work in the United States grew by 163 hours/year, or

approximately 1 month more, between 1969 and 1987 (1).

Lack of time is a commonly cited barrier to exercise (2);

unfortunately, current physical activity guidelines require a

noninconsequential time commitment (at least 30 minutes of

moderate-intensity activity most days of the week or at least

20 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days/

week, generating approximately 1,000 kcal/week) (3, 4).

Some individuals may choose to compress their exercise into

fewer days, such as during weekends only, giving rise to the

colloquial term weekend warriors. Although weekend

warriors exercise only once or twice a week, each activity

session can be prolonged, generating sufficient energy

expenditure to fall within current guidelines. However,

national surveys, which tend to emphasize the weekly

frequency of physical activity in their analyses of physical

activity trends, would not count weekend warriors as

being regularly active (5) or achieving recommended levels

of activity (6). Little is known about whether health benefits

are associated with such an activity pattern, so we investigated this question in relation to all-cause mortality.

Correspondence to Dr. I-Min Lee, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, 677 Huntington Avenue, Boston, MA 02115

(e-mail: ilee@rics.bwh.harvard.edu).

636

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

Physical activity improves health, and current recommendations encourage daily exercise. However, little is

known about any health benefits associated with infrequent bouts of exercise (e.g., 12 episodes/week) that

generate the recommended energy expenditure. The authors conducted a prospective cohort study among 8,421

men (mean age, 66 years) in the Harvard Alumni Health Study, without major chronic diseases, who provided

details about physical activity on mailed questionnaires in 1988 and 1993. Men were classified as sedentary

(expending <500 kcal/week), insufficiently active (500999 kcal/week), weekend warriors (1,000 kcal/week

from sports/recreation 12 times/week), or regularly active (all others expending 1,000 kcal/week). Between

1988 and 1997, 1,234 men died. The multivariate relative risks for mortality among the sedentary, insufficiently

active, weekend warriors, and regularly active men were 1.00 (referent), 0.75 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.62,

0.91), 0.85 (95% CI: 0.65, 1.11), and 0.64 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.73), respectively. In stratified analysis, among men

without major risk factors, weekend warriors had a lower risk of dying, compared with sedentary men (relative

risk = 0.41, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.81). This was not seen among men with at least one major risk factor (corresponding

relative risk = 1.02, 95% CI: 0.75, 1.38). These results suggest that regular physical activity generating 1,000 kcal/

week or more should be recommended for lowering mortality rates. However, among those with no major risk

factors, even 12 episodes/week generating 1,000 kcal/week or more can postpone mortality.

The Weekend Warrior and Risk of Mortality 637

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

The Harvard Alumni Health Study is an ongoing study of

men who matriculated as undergraduates at Harvard University between 1916 and 1950. This study is approved by the

Human Subjects Committee, Harvard School of Public

Health. Since 1962, alumni have periodically returned

mailed questionnaires on their health habits and health

status. For this analysis, 12,805 men who returned a survey

in 1988 were eligible. We excluded men reporting prevalent

cardiovascular disease, cancer, or diabetes in 1988 (n =

3,942), since these diseases may alter activity levels, and

men with missing physical activity information (n = 442),

leaving 8,421 men.

Assessment of physical activity and other predictors of

mortality

Ascertainment of mortality

We followed men after the return of the 1988 questionnaire through 1997 for mortality and obtained copies of official death certificates. Mortality follow-up is greater than 99

percent complete (13).

Statistical analyses

We first examined the baseline characteristics of the men

according to the four different physical activity patterns. We

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

RESULTS

At baseline, 17 percent of alumni were classified as

sedentary; 13 percent, insufficiently active; 7 percent,

weekend warriors; and 62 percent, regularly active.

Among the weekend warriors, 22 percent reported one

session of physical activity per week; 78 percent, two. Each

activity session lasted a median of 86 (interquartile range,

45135) minutes. The most common activities undertaken

by weekend warriors were tennis (38 percent), golf (13

percent), and gardening (9 percent).

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of men,

according to their physical activity pattern. The mean age of

all the men at baseline was 66.3 years, with weekend

warriors being the youngest. In general, the two most active

groups had a better health profile than the two least active

groups did. The exceptions were weight and diet: Weekend

warriors were the heaviest; they also were least likely to take

vitamin/mineral supplements, most likely to eat red meat,

and least likely to eat vegetables.

During follow-up, 1,234 men died. In age-adjusted analyses, weekend warriors were not at significantly lower risk

of follow-up, but regularly active men were (table 2).

Additional adjustment for smoking, diet, vitamin/mineral

supplements, and early parental mortality yielded similar

findings. Regularly active men had a statistically significant,

36 percent lower risk compared with sedentary men. In

multivariate analyses, the mortality rates among insufficiently active men and weekend warriors did not differ

significantly (p = 0.40), while the mortality rate among regularly active men was significantly lower than that among

weekend warriors (p = 0.03).

We then examined the association between physical

activity pattern and mortality rates separately among lowrisk men and high-risk men (figure 1). Low-risk men (34

percent) had none of the following risk factors at baseline;

high-risk men (66 percent) had at least one: smoking, overweight (body mass index of 25 kg/m2), history of hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. In both subgroups, regularly

active men were at significantly lower risk of dying during

follow-up compared with sedentary men. Among low-risk

men, weekend warriors also experienced lower risk of

mortality than did sedentary men. However, this did not hold

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

On the 1988 questionnaire, men reported their daily

walking and stair climbing. They also listed the sports and

recreational activities undertaken in the past week and the

frequency and duration of participation (7). This assessment

of physical activity has been shown to be reliable and valid

(810). On the basis of the energy cost of each activity (11),

we estimated the energy expended on walking, climbing

stairs, and all sports and recreational activities. We then

divided men into four groups, decided a priori, based on their

physical activity pattern: 1) sedentary, expending less than

500 kcal/week on all reported activities; 2) insufficiently

active, expending 500999 kcal/week in these same activities; 3) weekend warriors, expending 1,000 kcal/week or

more by participating in sports and recreational activities 1

2 times/week; and 4) regularly active, all others expending

1,000 kcal/week or more on all reported activities. (As an

approximate equivalent, 500 kcal/week can be translated to

about 75 minutes/week of brisk walking; 1,000 kcal/week,

about 150 minutes/week of brisk walking.) Groups 1 and 2

were separated because some studies have reported lower

mortality rates among individuals not quite fulfilling current

recommendations for 1,000 kcal/week of energy expenditure

(12).

On the same questionnaire, men also reported their age,

weight, height, cigarette smoking, diet, history of hypertension, and high cholesterol, as well as parental history of early

mortality (age <65 years). All data, except for diet and

parental history, were updated on another health questionnaire

in 1993.

then used proportional hazards regression (14, 15) to estimate the relative risks of mortality associated with these

physical activity patterns. The four activity patterns were

entered as three indicator variables in a single regression

model. Initially, we adjusted the relative risks for differences

in age only. We then also controlled for cigarette smoking,

alcohol consumption, red meat intake, vegetable intake,

vitamin/mineral supplements, and early parental mortality.

All variables were assessed at baseline in 1988 and updated

in 1993 using time-dependent analyses, except for diet, use

of supplements, and parental history. Finally, we examined

two subgroups of men separately: 1) low-risk men who had

none of these risk factorssmoking, overweight (body mass

index of 25 kg/m2), history of hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia; and 2) high-risk men who had at least one risk

factor.

638 Lee et al.

TABLE 1. Baseline characteristics, by physical activity pattern, of men in the Harvard Alumni Health Study, 19881997

Physical activity pattern*

Characteristic

Sedentary

(n = 1,453)

Insufficiently active

(n = 1,127)

Weekend warrior

(n = 580)

Regularly active

(n = 5,261)

68.4 (9.0)

66.2 (7.7)

64.7 (7.2)

65.9 (7.3)

Energy expenditure, kcal/week (median

(interquartile range))

210 (98350)

742 (644858)

2,360 (1,8033,177)

2,766 (1,7344,486)

Body mass index, kg/m2 (mean (SD))

25.1 (3.5)

24.7 (3.1)

25.3 (2.8)

24.5 (2.7)

Current smokers (%)

12.7

11.4

9.9

6.3

Consuming alcohol daily (%)

37.3

39.5

44.3

43.5

Taking vitamin/mineral supplements (%)

44.3

43.6

37.2

46.3

Consuming <1 serving/week of red meat

(%)

19.9

21.8

17.1

24.9

Consuming 3 servings/day of

vegetables (%)

13.5

12.4

11.2

15.1

History of hypertension (%)

30.2

26.3

23.1

26.1

History of hypercholesterolemia (%)

17.2

20.2

16.9

19.0

Early parental mortality (<65 years) (%)

33.3

31.6

29.3

33.1

* Physical activity pattern is defined as follows: sedentary (men expending <500 kcal/week in walking, climbing stairs, and sports/

recreation); insufficiently active (men expending 500999 kcal/week in these same activities); weekend warrior (men expending 1,000 kcal/

week by participation in sports/recreation 12 times/week); and regularly active (all other men expending 1,000 kcal/week in walking,

climbing stairs, and sports/recreation). Both weekend warrior and regularly active groups meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/

American College of Sports Medicine physical activity recommendation with respect to energy expenditure, that is, at least 1,000 kcal/week

(Pate et al. JAMA 1995;273:4027) (3).

SD, standard deviation.

for weekend warriors in the high-risk group. Among lowrisk men, the multivariate relative risks of all-cause mortality

associated with sedentary men, insufficiently active men,

weekend warriors, and regularly active men were 1.00

(referent), 0.56 (95 percent confidence interval (CI): 0.40,

0.79), 0.41 (95 percent CI: 0.21, 0.81), and 0.58 (95 percent

CI: 0.46, 0.74), respectively. For high-risk men, they were

1.00 (referent), 0.84 (95 percent CI: 0.67, 1.05), 1.02 (95

percent CI: 0.75, 1.38), and 0.61 (95 percent CI: 0.52, 0.78),

respectively.

TABLE 2. Relative risks of mortality according to physical activity pattern, Harvard Alumni Health

Study, 19881997

No. of

men

No. of

deaths

Age-adjusted

relative risk

95%

confidence

interval

Multivariateadjusted relative

risk

95%

confidence

interval

Sedentary

1,453

346

1.00

Referent

1.00

Referent

Insufficiently active

1,127

191

0.75

0.63, 0.90

0.75

0.62, 0.91

580

73

0.82

0.63, 1.07

0.85

0.65, 1.11

5,261

624

0.61

0.53, 0.69

0.64

0.55, 0.73

Physical activity

pattern*

Weekend warrior

Regularly active

* Physical activity pattern is defined as follows: sedentary (men expending <500 kcal/week in walking,

climbing stairs, and sports/recreation); insufficiently active (men expending 500999 kcal/week in these

same activities); weekend warrior (men expending 1,000 kcal/week by participation in sports/recreation 1

2 times/week); and regularly active (all other men expending 1,000 kcal/week in walking, climbing stairs,

and sports/recreation). Both weekend warrior and regularly active groups meet the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention/American College of Sports Medicine physical activity recommendation with respect

to energy expenditure, that is, at least 1,000 kcal/week (Pate et al. JAMA 1995;273:4027) (3). The numbers

of men and deaths are distributed according to the physical activity pattern at baseline.

Adjusted for age, cigarette smoking (never, past, or current), alcohol consumption (never, 13 drinks/

week, 46 drinks/week, or daily), red meat intake (<3 servings/month, 12 servings/week, or 3 servings/

week), vegetable intake (<1 serving/day, 12 servings/day, or 3 servings/day), vitamin/mineral supplements,

and early parental mortality (both no or yes).

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

Age, years (mean (SD))

The Weekend Warrior and Risk of Mortality 639

DISCUSSION

Physical activity clearly is associated with health benefits

(4, 16, 17), and current recommendations encourage daily

exercise (3, 4). Unfortunately, lack of time is a common

barrier to exercise (2). Little is known about any health benefits associated with the so-called weekend warrior pattern

an exercise pattern that generates sufficient energy to satisfy

current physical activity recommendations (1,000 kcal/

week) but over 12 sessions/weekinstead of the recommended most days of the week. The present study suggests

that a pattern of regular physical activity generating 1,000

kcal/week or more should be recommended for lowering

mortality rates. However, among low-risk men without

major risk factors, even 12 episodes/week of physical

activity that generate 1,000 kcal/week or more can postpone

mortality.

High-risk men may not benefit from sporadic physical

activity, such as the weekend warrior pattern, because some

beneficial effects of physical activity are short-lived. Hypertensive men and women, aged 6069 years, experienced

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

decreases in systolic blood pressure immediately after a bout

of exercise. However, the reductions were no longer

sustained by 180 minutes postexercise (18). Some acute

effects may also be augmented by chronic, regular activity.

Among men with hypertriglyceridemia, fasting triglyceride

levels were lower on the morning after a bout of exercise

than after a day without exercise. Over a 4-day period, when

men walked daily, progressive decreases in fasting triglyceride levels occurred (19). Thus, high-risk men who are not

regularly active may not experience the full benefits of physical activity.

The present analyses add to earlier findings from the

Harvard Alumni Health Study, which had shown physical

activity to be associated with lower risk of premature

mortality and chronic diseases (2024). Additionally, the

data indicated that changing from an inactive to active way

of life could postpone mortality (25). Previous analyses also

supported the notion that physical activity can be accumulated in shorter bouts (instead of a single session) in the day

(13). The present analyses extend previous findings in

showing that regular physical activity is preferable for post-

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

FIGURE 1. Relative risks of mortality according to physical activity pattern among low-risk men and high-risk men, Harvard Alumni Health

Study, 19881997. Lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Relative risks are adjusted for age, cigarette smoking (never, past, or current),

alcohol consumption (never, 13 drinks/week, 46 drinks/week, or daily), red meat intake (<3 servings/month, 12 servings/week, or 3 servings/

week), vegetable intake (<1 serving/day, 12 servings/day, or 3 servings/day), vitamin/mineral supplements, and early parental mortality (both

no or yes). Physical activity pattern is defined as follows: sedentary (men expending <500 kcal/week in walking, climbing stairs, and sports/

recreation); insufficiently active (men expending 500999 kcal/week in these same activities); weekend warrior (men expending 1,000 kcal/

week by participation in sports/recreation 12 times/week); and regularly active (all other men expending 1,000 kcal/week in walking, climbing

stairs, and sports/recreation). Both weekend warrior and regularly active groups meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/American

College of Sports Medicine physical activity recommendation with respect to energy expenditure, that is, at least 1,000 kcal/week (Pate et al.

JAMA 1995;273:4027) (3). Low-risk men had none of the following risk factors at baseline, but high-risk men had at least one: cigarette smoking,

overweight (body mass index of 25 kg/m2), history of hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia.

640 Lee et al.

were older and likely to be retired; thus, they might not truly

be weekend warriors. Additionally, they were men of

higher socioeconomic status who likely possessed healthier

behaviors. It is unclear how generalizable the present findings may be to those who are younger, women, and persons

with different socioeconomic backgrounds (although physical activity also has been shown to benefit women and

minorities (33)). Although detailed, the physical activity

information was self-reported. Nonetheless, such selfreports have been shown to be reliable and valid (810).

Additionally, we estimated the energy expended on physical

activities using a widely used compendium developed with

data primarily from young to middle-aged men (11).

However, because the data were collected prospectively, any

bias should be toward the null. The present analyses

controlled for several potential confounders, but because this

is an observational study, confounding cannot be completely

eliminated. There also were relatively few weekend

warriors, which limited the statistical power of the analyses.

Finally, it is possible that the findings reflect decreased

activity levels among men who were in poor health. We tried

to minimize this bias by excluding men with cardiovascular

disease, cancer, and diabetes.

In conclusion, the present observations suggest that a

pattern of regular physical activity generating 1,000 kcal/week

or more should be recommended for lowering mortality rates.

However, among men without major risk factors, even 12

episodes/week of physical activity that generate 1,000 kcal/

week or more can postpone mortality. Thus, for individuals

with no major risk factors who are too busy for daily exercise,

this may offer a measure of encouragement.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by research grants from the

National Institutes of Health (HL67429 and CA91213) and

the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The authors are grateful to Sarah E. Freeman, Rita W.

Leung, Doris C. Rosoff, and Alvin L. Wing for their help

with the College Alumni Health Study.

This is report no. LXXXV in a series on chronic disease in

former college students.

REFERENCES

1. Schor J. The overworked American. New York, NY: Basic

Books, 1991.

2. Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, et al. Correlates of adults participation in physical activity: review and update. Med Sci

Sports Exerc 2002;34:19962001.

3. Pate RR, Pratt M, Blair SN, et al. Physical activity and public

health. A recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. JAMA 1995;273:4027.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical activity and health. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA:

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health

Promotion, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

poning mortality. However, among low-risk men, if all they

can find time for is 12 episodes/week of activity that

generate the requisite energy expenditure, even this is

helpful.

It should be noted that less stringent requirements for

physical activity do not guarantee greater participation in

this behavior. The determinants of physical activity are

complex and likely to include personal (e.g., demographic,

psychological), behavioral, and environmental (e.g., physical, social, cultural, time) factors (26). Although lack of

time is often given as a reason for not exercising, this can

represent a true barrier, a perceived barrier, a lack of time

management skills, or merely an excuse.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine clinical endpoints among persons colloquially called weekend

warriors. In a nonrandomized trial, 55 healthy Finnish men

were asked to play an 18-hole round of golf twice a week for

20 weeks; they averaged 10 hours/week of play (27).

Compared with sedentary controls, significant improvements occurred among golfers in adiposity, physical fitness,

and lipid profile. These data suggest that less frequent bouts

of activity, which are more easily scheduled into a busy lifestyle, can have some health benefits if sufficient energy is

expended. One concern with sporadic physical activity is

that risk of musculoskeletal injuries may be higher. Unfortunately, neither the Finnish study nor the present study

collected data regarding injuries. Other studies have shown

that the risk of musculoskeletal injuries increases with higher

intensity and total duration of physical activity (28, 29).

However, when the same activities are performed for the

same total duration per week, it is unknown whether the risk

of injury differs between those who exercise 12 times/

week, compared with more frequently.

One issue that needs discussion concerns how much total

physical activity we need for health. There is some confusion

because of two apparently contradictory recommendations

from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/

American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the Institute of Medicine. The CDC/ACSM recommendation,

released in 1995, calls for at least 30 minutes of moderateintensity physical activity most days of the week (3). This

recommendation was developed with an emphasis on healthrelated outcomes but with no particular focus on weight

control. In contrast, the 2002 Institute of Medicine guideline

of 60 minutes/day of moderate-intensity activity emphasized

weight control and was part of a larger recommendation for

healthy diet (30). The findings from the present study add to

the overall evidence that the CDC/ACSM recommendation

can decrease the risk of premature mortality. Two recent

randomized clinical trials also showed that the CDC/ACSM

recommendation is sufficient for weight loss in overweight

persons, provided caloric intake is restricted (31), and for

prevention of weight gain, in the absence of dietary change

(32).

The strengths of the present study include extensive information on physical activity (including details on type,

frequency, and duration) that was updated over time. We

also collected information on many variables that could

confound the relation between physical activity and

mortality. However, several limitations exist. Participants

The Weekend Warrior and Risk of Mortality 641

Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:636641

20. Lee IM, Hsieh CC, Paffenbarger RS Jr. Exercise intensity and

longevity in men. The Harvard Alumni Health Study. JAMA

1995;273:117984.

21. Paffenbarger RS Jr, Wing AL, Hyde RT. Physical activity as an

index of heart attack risk in college alumni. Am J Epidemiol

1978;108:16175.

22. Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Lee IM. Physical activity and

coronary heart disease in men: the Harvard Alumni Health

Study. Circulation 2000;102:97580.

23. Helmrich SP, Ragland DR, Leung RW, et al. Physical activity

and reduced occurrence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 1991;325:14752.

24. Lee IM, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hsieh C. Physical activity and risk

of developing colorectal cancer among college alumni. J Natl

Cancer Inst 1991;83:13249.

25. Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hyde RT, Wing AL, et al. The association

of changes in physical-activity level and other lifestyle characteristics with mortality among men. N Engl J Med 1993;328:

53845.

26. Dishman RK, Washburn RA, Heath GA. Adopting and maintaining a physically active lifestyle. In: Physical activity epidemiology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2004:391437.

27. Parkkari J, Natri A, Kannus P, et al. A controlled trial of the

health benefits of regular walking on a golf course. Am J Med

2000;109:1028.

28. Koplan JP, Rothenberg RB, Jones EL. The natural history of

exercise: a 10-yr follow-up of a cohort of runners. Med Sci

Sports Exerc 1995;27:11804.

29. Hootman JM, Macera CA, Ainsworth BE, et al. Epidemiology

of musculoskeletal injuries among sedentary and physically

active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2002;34:83844.

30. Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids,

cholesterol, protein, and amino acids (macronutrients). Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2002.

31. Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Gallagher KI, et al. Effect of exercise

duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary

women: a randomized trial. JAMA 2003;290:132330.

32. Slentz CA, Duscha BD, Johnson JL, et al. Effects of the amount

of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of

central obesity: STRRIDEa randomized controlled study.

Arch Intern Med 2004;164:319.

33. Manson JE, Greenland P, LaCroix AZ, et al. Walking compared with vigorous exercise for the prevention of cardiovascular events in women. N Engl J Med 2002;347:71625.

Downloaded from aje.oxfordjournals.org by guest on March 12, 2011

Department of Health and Human Services, 1996.

5. Schoenborn CA, Barnes PM. Leisure-time physical activity

among adults: United States, 19971998. Adv Data 2002;325:

123.

6. Physical activity trendsUnited States, 19901998. MMWR

Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:1669.

7. Lee IM, Paffenbarger RS Jr, Hsieh CC. Time trends in physical

activity among college alumni, 19621988. Am J Epidemiol

1992;135:91525.

8. Albanes D, Conway JM, Taylor PR, et al. Validation and comparison of eight physical activity questionnaires. Epidemiology

1990;1:6571.

9. Ainsworth BE, Leon AS, Richardson MT, et al. Accuracy of the

College Alumnus Physical Activity Questionnaire. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:140311.

10. Washburn RA, Smith KW, Goldfield SR, et al. Reliability and

physiologic correlates of the Harvard Alumni Activity Survey

in a general population. J Clin Epidemiol 1991;44:131926.

11. Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Leon AS, et al. Compendium of

physical activities: classification of energy costs of human

physical activities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:7180.

12. Lee IM, Skerrett PJ. Physical activity and all-cause mortality:

what is the dose-response relation? Med Sci Sports Exerc 2001;

33(suppl):S45971; discussion S4934.

13. Lee IM, Sesso HD, Paffenbarger RS Jr. Physical activity and

coronary heart disease risk in men: does the duration of exercise

episodes predict risk? Circulation 2000;102:9816.

14. SAS Institute, Inc. The SAS system, release 8.2 (TS2M0).

Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc, 1999.

15. Cox DR. Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J

R Stat Soc (B) 1972;34:187220.

16. Blair SN, Kampert JB, Kohl HW 3rd, et al. Influences of cardiorespiratory fitness and other precursors on cardiovascular

disease and all-cause mortality in men and women. JAMA

1996;276:20510.

17. Myers J, Prakash M, Froelicher V, et al. Exercise capacity and

mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J

Med 2002;346:793801.

18. Hagberg JM, Montain SJ, Martin WH 3rd. Blood pressure and

hemodynamic responses after exercise in older hypertensives. J

Appl Physiol 1987;63:2706.

19. Gyntelberg F, Brennan R, Holloszy JO, et al. Plasma triglyceride lowering by exercise despite increased food intake in

patients with type IV hyperlipoproteinemia. Am J Clin Nutr

1977;30:71620.

Вам также может понравиться

- Exercise Is Medicine: How To Get You and Your Patients MovingДокумент120 страницExercise Is Medicine: How To Get You and Your Patients MovingMuhammad AbdullahОценок пока нет

- Health and Cycling: Professor Bruce Lynn, UCLДокумент36 страницHealth and Cycling: Professor Bruce Lynn, UCLNadya ShabrinaОценок пока нет

- 1 s2.0 S0735109714027466 MainДокумент10 страниц1 s2.0 S0735109714027466 MainEmail KerjaОценок пока нет

- Essay 2 BibliographyДокумент10 страницEssay 2 Bibliographyapi-579014618Оценок пока нет

- Leitzmann Et Al., (2007) Physical Activity RecommendationsДокумент8 страницLeitzmann Et Al., (2007) Physical Activity RecommendationsAna Flávia SordiОценок пока нет

- Relative Intensity of Physical Activity and Risk of Coronary Heart DiseaseДокумент17 страницRelative Intensity of Physical Activity and Risk of Coronary Heart DiseaseWidya SyahdilaОценок пока нет

- Haskell 2007Документ12 страницHaskell 2007muratigdi96Оценок пока нет

- E.F y AlzheimerДокумент3 страницыE.F y AlzheimerpaoОценок пока нет

- Exercise GuidelineДокумент5 страницExercise GuidelineRina RaehanaОценок пока нет

- Exercice Is MedicineДокумент55 страницExercice Is MedicineDario MoralesОценок пока нет

- mss51270 1324..1339Документ16 страницmss51270 1324..1339matthewquan711Оценок пока нет

- JNC 8 Ala Ala TrustlineДокумент64 страницыJNC 8 Ala Ala TrustlineameliarumentaОценок пока нет

- Research Project-2Документ12 страницResearch Project-2api-663561390Оценок пока нет

- Dietary Protein and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Middle-Aged Men1-3 Sarah Rosner PДокумент8 страницDietary Protein and Risk of Ischemic Heart Disease in Middle-Aged Men1-3 Sarah Rosner Ppaulobrasil.ortopedistaОценок пока нет

- Choosing the StrongPath: Reversing the Downward Spiral of AgingОт EverandChoosing the StrongPath: Reversing the Downward Spiral of AgingРейтинг: 3 из 5 звезд3/5 (2)

- Leisure Time Physical Activity and Mortality A Detailed Pooled Analysis of The Dose-Response RelationshipДокумент9 страницLeisure Time Physical Activity and Mortality A Detailed Pooled Analysis of The Dose-Response RelationshipAgnes Nina EurekaОценок пока нет

- Smoking, Antioxidant Vitamins, and The Risk of Hip FractureДокумент7 страницSmoking, Antioxidant Vitamins, and The Risk of Hip FractureAnonymous pJfAvlОценок пока нет

- The Age Antidote: Len Kravitz, PH.DДокумент6 страницThe Age Antidote: Len Kravitz, PH.D3520952Оценок пока нет

- A Group of 500 Women Whose Health May Depart Notably From The Norm: Protocol For A Cross-Sectional SurveyДокумент12 страницA Group of 500 Women Whose Health May Depart Notably From The Norm: Protocol For A Cross-Sectional Surveyhanna.oravecz1Оценок пока нет

- Physical Health Correlates of Overprediction of Physical Discomfort During ExerciseДокумент14 страницPhysical Health Correlates of Overprediction of Physical Discomfort During ExerciseJaviera Soto AndradeОценок пока нет

- Introduction To Exercise PrescriptionДокумент46 страницIntroduction To Exercise PrescriptionabhijeetОценок пока нет

- Jurnal Kesehatan MasyarakatДокумент8 страницJurnal Kesehatan MasyarakatDana AdwanОценок пока нет

- DownloadДокумент7 страницDownloadcesar8319Оценок пока нет

- García Hermoso2018Документ19 страницGarcía Hermoso2018Sam Steven Hernandez JañaОценок пока нет

- Health Behavior: An Overview of Effects & Issues: Jimenez, A., Beedie, C. and Ligouri, GДокумент16 страницHealth Behavior: An Overview of Effects & Issues: Jimenez, A., Beedie, C. and Ligouri, GAbdurrahamanОценок пока нет

- Am. J. Epidemiol.-2003-Ma-85-92Документ8 страницAm. J. Epidemiol.-2003-Ma-85-92Eima Siti NurimahОценок пока нет

- Hydratacion Indices Longitud Acute IJSNEM 2010Документ9 страницHydratacion Indices Longitud Acute IJSNEM 2010RosaОценок пока нет

- Nutrition and Physical Activity For Health: John M. Jakicic, PHDДокумент23 страницыNutrition and Physical Activity For Health: John M. Jakicic, PHDtimothyhwangОценок пока нет

- Effects of Low-Intensity Resistance Exercise With Vascular Occlusion On Physical Function in Healthy Elderly People.-2Документ7 страницEffects of Low-Intensity Resistance Exercise With Vascular Occlusion On Physical Function in Healthy Elderly People.-2Ingrid Ramirez PОценок пока нет

- Osteo 1Документ6 страницOsteo 1Ardhyan ArdhyanОценок пока нет

- (2017) Running Does Not Increase Symptoms or Structural Progression in People With Knee Osteoarthritis - Data From The Osteoarthritis InitiativeДокумент8 страниц(2017) Running Does Not Increase Symptoms or Structural Progression in People With Knee Osteoarthritis - Data From The Osteoarthritis Initiativecalixto1995Оценок пока нет

- Body Mass Index and Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Prospective Study in Korean MenДокумент7 страницBody Mass Index and Ischemic and Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Prospective Study in Korean MenSri Wahyuni HarliОценок пока нет

- Relationship Between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and MorbidityДокумент12 страницRelationship Between Urban Sprawl and Physical Activity, Obesity, and MorbidityMaría HurtadoОценок пока нет

- Grip Strength, Body CompositionДокумент8 страницGrip Strength, Body CompositionFPSMОценок пока нет

- Associations of Changes in Exercise Level With Subsequent Disability Among Seniors: A 16-Year Longitudinal StudyДокумент6 страницAssociations of Changes in Exercise Level With Subsequent Disability Among Seniors: A 16-Year Longitudinal StudymartinОценок пока нет

- Long-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US AdultsДокумент12 страницLong-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US AdultsANDRÉ GUIMARÃESОценок пока нет

- Physical Inactivity: Associated Diseases and Disorders: ReviewДокумент18 страницPhysical Inactivity: Associated Diseases and Disorders: ReviewJuan Pablo Casanova AnguloОценок пока нет

- 04 - Cardiometabolic Effects of High-Intensity Hybrid Functional Electrical Stimulation Exercise After Spinal Cord InjuryДокумент20 страниц04 - Cardiometabolic Effects of High-Intensity Hybrid Functional Electrical Stimulation Exercise After Spinal Cord Injurywellington contieroОценок пока нет

- Jurnal FisiologiДокумент8 страницJurnal FisiologiRFALWОценок пока нет

- Schroder 2005Документ17 страницSchroder 2005s3rinadataОценок пока нет

- Skeletal Muscle Hypertrophy After Aerobic Exercise TrainingДокумент9 страницSkeletal Muscle Hypertrophy After Aerobic Exercise TrainingAlbert CalvetОценок пока нет

- Epidemiology of MSK Impairment and DisabilityДокумент6 страницEpidemiology of MSK Impairment and DisabilityMd. Ariful IslamОценок пока нет

- Drinking Patterns and Body Mass Index in Never Smokers: National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2001Документ9 страницDrinking Patterns and Body Mass Index in Never Smokers: National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2001miculmucОценок пока нет

- Lewis Et Al - MrOS Fractures - JBMR2007Документ9 страницLewis Et Al - MrOS Fractures - JBMR2007chuckc123Оценок пока нет

- Effects of Diet, Physical Activity and Performance, and Body Weight On Incident Gout in Ostensibly Healthy, Vigorously Active MenДокумент8 страницEffects of Diet, Physical Activity and Performance, and Body Weight On Incident Gout in Ostensibly Healthy, Vigorously Active Menristi hutamiОценок пока нет

- (15435474 - Journal of Physical Activity and Health) Socioeconomic Predictors of A Sedentary Lifestyle - Results From The 2001 National Health SurveyДокумент12 страниц(15435474 - Journal of Physical Activity and Health) Socioeconomic Predictors of A Sedentary Lifestyle - Results From The 2001 National Health Surveyconstance yanОценок пока нет

- Sarcopenic Obesity Predicts Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Disability in The ElderlyДокумент10 страницSarcopenic Obesity Predicts Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Disability in The ElderlyFranchesca OrtizОценок пока нет

- Life Extension Magazine: The 10 Most Important Blood TestsДокумент6 страницLife Extension Magazine: The 10 Most Important Blood TestsJaffer AftabОценок пока нет

- WPTDay11 Cancer Fact Sheet C6 PDFДокумент3 страницыWPTDay11 Cancer Fact Sheet C6 PDFDr. Krishna N. SharmaОценок пока нет

- Acsm Current Comment: Physiology of AgingДокумент2 страницыAcsm Current Comment: Physiology of AgingTeoОценок пока нет

- Long QuizДокумент6 страницLong QuizMae EsmadeОценок пока нет

- Jama Physical ActivityДокумент3 страницыJama Physical ActivityflorОценок пока нет

- Alternative Medicine Joins The MainstreamДокумент68 страницAlternative Medicine Joins The Mainstreamccprado1Оценок пока нет

- Leisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality RiskДокумент19 страницLeisure-Time Running Reduces All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality Riskmonalisa.fiscalОценок пока нет

- Jurnal ObesitasДокумент20 страницJurnal ObesitasTan Endy100% (1)

- Am J Clin Nutr 2008 Paddon Jones 1562S 6SДокумент5 страницAm J Clin Nutr 2008 Paddon Jones 1562S 6ScintaОценок пока нет

- The Female Athlete Triad: A Clinical GuideОт EverandThe Female Athlete Triad: A Clinical GuideCatherine M. GordonОценок пока нет

- Eng 2 Exercise Research PaperДокумент12 страницEng 2 Exercise Research Paperapi-534316399Оценок пока нет

- Oxandrolone in Older MenДокумент9 страницOxandrolone in Older MenJorge FernándezОценок пока нет

- Informed ConsentДокумент32 страницыInformed ConsentSara Montañez Barajas0% (1)

- Recruitment & RetentionДокумент20 страницRecruitment & Retentionjessica maria vasquez lopez100% (1)

- Part 1: Introduction Part 2: QA and Monitoring Role Part 3: Trial Monitoring Activities Part 4: Summary of Key PointsДокумент12 страницPart 1: Introduction Part 2: QA and Monitoring Role Part 3: Trial Monitoring Activities Part 4: Summary of Key PointsRenzo FernandezОценок пока нет

- Investigational New DrugsДокумент16 страницInvestigational New DrugsVirgil CendanaОценок пока нет

- Participant Safety and Adverse EventsДокумент27 страницParticipant Safety and Adverse EventsVirgil CendanaОценок пока нет

- Part 1: Introduction Part 2: Responsibilities by Role Part 3: Summary of Key PointsДокумент13 страницPart 1: Introduction Part 2: Responsibilities by Role Part 3: Summary of Key PointsFaye BaliloОценок пока нет

- MetodoДокумент20 страницMetodoSara Montañez BarajasОценок пока нет

- The Research ProtocolДокумент17 страницThe Research ProtocolHiếu NhiОценок пока нет

- A Cross Sectional Study of Fasting Serum Magnesium Levels in The Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Relation To Diabetic ComplicationsДокумент5 страницA Cross Sectional Study of Fasting Serum Magnesium Levels in The Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Its Relation To Diabetic ComplicationsRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Pi Is 0091674917309193Документ9 страницPi Is 0091674917309193Annisa YutamiОценок пока нет

- DocДокумент14 страницDocSara Montañez BarajasОценок пока нет

- 7979 12179 1 SMДокумент2 страницы7979 12179 1 SMRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Research Misconduct PDFДокумент15 страницResearch Misconduct PDFAnonymous b27E5uXlОценок пока нет

- The Relationship of Plasma Adipsin Adiponectin VasДокумент9 страницThe Relationship of Plasma Adipsin Adiponectin VasRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- DSC-management of Vitamin D DeficiencyДокумент17 страницDSC-management of Vitamin D DeficiencyRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Nutrients: Vitamin D Intake and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesДокумент12 страницNutrients: Vitamin D Intake and Risk of Type 1 Diabetes: A Meta-Analysis of Observational StudiesRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Assessment of Precautionary Measures Against COVID-19 in Indonesian WorkplacesДокумент8 страницAssessment of Precautionary Measures Against COVID-19 in Indonesian WorkplacesRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Nutrients: Role of Gut Microbiota On Onset and Progression of Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM)Документ26 страницNutrients: Role of Gut Microbiota On Onset and Progression of Microvascular Complications of Type 2 Diabetes (T2DM)Robert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Guidance On How To Use QUADAS-C (v2020.03.12)Документ21 страницаGuidance On How To Use QUADAS-C (v2020.03.12)Robert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Anthropometry Features Among Seemingly Healthy Young AdultsДокумент6 страницCardiovascular Disease Risk Factors and Anthropometry Features Among Seemingly Healthy Young AdultsRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Pro File of The Gut Microbiota of Adults With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewДокумент12 страницPro File of The Gut Microbiota of Adults With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Diagnosis and Management of HypocalcemiaДокумент11 страницDiagnosis and Management of HypocalcemiamdmmmОценок пока нет

- 1738-Article Text-17917-1-10-20191212Документ12 страниц1738-Article Text-17917-1-10-20191212Robert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Phenolic Compounds Impact On Rheumatoid Arthritis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Microbiota ModulationДокумент39 страницPhenolic Compounds Impact On Rheumatoid Arthritis, Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Microbiota ModulationRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Survival Analysis in RДокумент8 страницSurvival Analysis in RRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Survival Analysis in R PDFДокумент16 страницSurvival Analysis in R PDFmarciodoamaralОценок пока нет

- Body Fluids: Fluid and ElectrolytesДокумент17 страницBody Fluids: Fluid and ElectrolytesRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Body Fluids: Fluid and ElectrolytesДокумент17 страницBody Fluids: Fluid and ElectrolytesRobert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- Alpha and Beta ThalassemiaДокумент6 страницAlpha and Beta ThalassemiaSi vis pacem...100% (1)

- NCCN Guidelines For Multiple Myeloma V.3.2016 - Web Teleconference Interim Update On 12/14/15Документ3 страницыNCCN Guidelines For Multiple Myeloma V.3.2016 - Web Teleconference Interim Update On 12/14/15Robert DwitamaОценок пока нет

- DLP in Mapeh 9Документ4 страницыDLP in Mapeh 9Joan B LangamОценок пока нет

- Unit 7 - What Do You Like Doing? (1) +Документ6 страницUnit 7 - What Do You Like Doing? (1) +Ngọc BíchОценок пока нет

- Swimming, in Recreation and Sports, The Propulsion of The Body Through Water by Combined ArmДокумент7 страницSwimming, in Recreation and Sports, The Propulsion of The Body Through Water by Combined ArmDaisy La MadridОценок пока нет

- History of Football: Quick Summarywith StoriesДокумент9 страницHistory of Football: Quick Summarywith StoriesshettyОценок пока нет

- Bloom v. Clark Evidence ISOДокумент189 страницBloom v. Clark Evidence ISOmary engОценок пока нет

- Decatur-DeKalb Family YMCA Pool ScheduleДокумент2 страницыDecatur-DeKalb Family YMCA Pool ScheduleMetro Atlanta YMCAОценок пока нет

- Sport SalariesДокумент5 страницSport SalariesAndrew Taylor WoolleyОценок пока нет

- P6 Interview QuestionsДокумент4 страницыP6 Interview QuestionsLi Yinlai100% (1)

- Английский 4-Кл 1 - ТЕТРАДЬДокумент52 страницыАнглийский 4-Кл 1 - ТЕТРАДЬЯрослав СтефкинОценок пока нет

- Lamborghini Pirelli BrochureДокумент16 страницLamborghini Pirelli Brochuresharky67Оценок пока нет

- DHBB CBG (ĐĐX) 2019 L10Документ13 страницDHBB CBG (ĐĐX) 2019 L10Tuyền Nguyễn Thị ÚtОценок пока нет

- MR Protein - Powerbuilding ProgramДокумент10 страницMR Protein - Powerbuilding ProgramhassanОценок пока нет

- 1998 Campagnolo CatalogДокумент33 страницы1998 Campagnolo CatalogTango OscarОценок пока нет

- Edlebrock Pleads Guilty: The Delphos HeraldДокумент16 страницEdlebrock Pleads Guilty: The Delphos HeraldThe Delphos HeraldОценок пока нет

- Rules For The 2018 National Robotics Competition PDFДокумент4 страницыRules For The 2018 National Robotics Competition PDFJeseu Yeomsu JaliОценок пока нет

- Lasker: Move by MoveДокумент26 страницLasker: Move by MoveArturo GonzalezОценок пока нет

- Japanese CultureДокумент23 страницыJapanese CultureWaqi Je100% (1)

- Tabela Muscle 2023Документ6 страницTabela Muscle 2023Alison WinclerОценок пока нет

- Cat Competicion 2023Документ48 страницCat Competicion 2023amartirosОценок пока нет

- C-Bond Interhigh - Track Starting Lists - 21 Feb 2024Документ25 страницC-Bond Interhigh - Track Starting Lists - 21 Feb 2024ee8757388Оценок пока нет

- Best of Robert RingerДокумент211 страницBest of Robert RingerSanti Dewi Setiawan100% (6)

- Altaf CVДокумент2 страницыAltaf CVAyesha AltafОценок пока нет

- Chris Hemsworth Workout - The God of Thunder's Thor Workout TRAINДокумент15 страницChris Hemsworth Workout - The God of Thunder's Thor Workout TRAINeldelmoño luci100% (1)

- Total-Body Workbook: External Oblique Rectus AbdominisДокумент5 страницTotal-Body Workbook: External Oblique Rectus Abdominisrayk24zzzОценок пока нет

- Daily Assessment - X - Descriptive TextДокумент5 страницDaily Assessment - X - Descriptive TextnoorfitriamaliaОценок пока нет

- August 2021 - July 2022Документ12 страницAugust 2021 - July 2022Наталия ЧуйковаОценок пока нет

- FIBA Officiating SignalsДокумент6 страницFIBA Officiating SignalsAhle MaeОценок пока нет

- Untitled Presentation-2Документ47 страницUntitled Presentation-2api-442144248Оценок пока нет

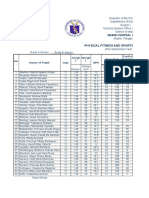

- Consolidation Physical Fitness Test FormДокумент6 страницConsolidation Physical Fitness Test Formvenus velonzaОценок пока нет

- The ICC Cricket ODI World Cup 2023 Scdule PDFДокумент4 страницыThe ICC Cricket ODI World Cup 2023 Scdule PDFShampa GhoshОценок пока нет